In the 1950s surfing blossomed. The aquatic pastime expanded its reach with the discovery of new beaches and the organization of the first national and international championships. These events set the bar for all championships to come and raised the competitive level of Peruvian athletes. And women were no longer mere spectators. They abandoned the shore to join the waves as active participants, bringing their enthusiasm and beauty with them. The remarkable surf sessions at the pointbreak called Kon Tiki and the fortification of Club Waikiki as the stronghold of South American surfing make these years an unforgettable era.

Hall McNicholls, an American pilot who worked for Panagra airlines, had an unlimited passion for surfing running through his veins. Flying the route between California and Peru, over the years McNicholls had established close friendships with the Waikiki Club surfers and would ride the waves of Miraflores with them any time he landed in Peru.

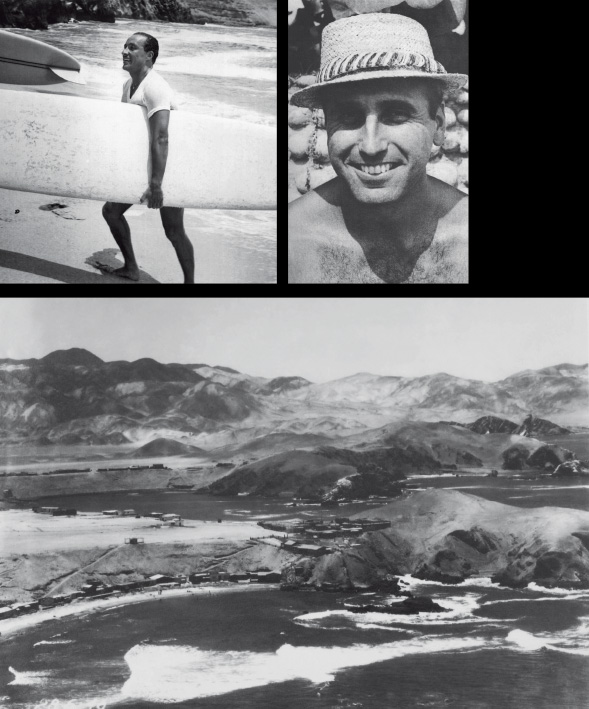

One summer morning in 1953, as McNicholls and his friend and co-pilot, John Green, were preparing to land in Lima. They circled over Punta Hermosa Bay and witnessed an impeccable set of waves marching across the blue sea. During the winter months, when the fog lay thick over Lima, McNicholls thought he might have seen something in the waters below but couldn’t be sure. Then, on that clear, sunny morning in 1953, his suspicions were confirmed. He made another pass over the point and indeed there were perfectly shaped waves pouring in from the outer waters. They were running flawlessly through the middle of the beautiful bay.

Thrilled by what he’d just witnessed, McNicholls landed safely at the airport in Limatambo, Lima’s old airport. He waited anxiously for the passengers to disembark before flinging himself in a taxi. He had to go find his friends at Club Waikiki. Arriving at 4:00 in the afternoon, McNicholls found club members hanging out and watching Dogny surfing with one of the most beautiful women of the season on top of his shoulders. When Hall arrived the tie of his uniform was loose, his jacket folded under his arm, pilot cap in hand, and a huge smile stretched across his tanned face.

“Hey guys, I think I have discovered a great beach further down south,” said Mc Nicholls in his broken Spanish. The words had barely left his lips before he was surrounded. The Gringo, a nickname of endearment that the Waikiki members had given McNicholls, had won their respect and approval and they knew he would never joke about something as important as this. They were all ears. Among the surfers on hand was the great Eduardo Arena, Guillermo “Pancho” Weise, and an excited teenager whose life would be forever changed by the news McNicholls brought, Pitty Block. The Gringo gave them extensive descriptions of the waves he had seen and convinced them he was capable of taking them there. “Why not?” said Dogny. Like that the group started to plan the details of Peru’s first surfari. The next day they headed out in a truck loaded and with their boards and accompanied by the “surfboard caddies,” who would help get their boards to the shore. “Gringo, are you sure you know how to get there?” asked one of the Peruvian surfers.

“I’m completely certain. Thirty miles south, I’m sure of it,” answered McNicholls, as if he had been waiting for that very question his whole life. The description McNicholls had offered had been so detailed and riveting that a murmur of admiration had echoed against the rocks of the beach when he had said, “Those waves are like the waves of Makaha.” It is probable that several of the surfers did not sleep a wink the night before they departed. As the caravan disembarked towards the secret beach, The Gringo went in the first car guiding the rest. Carried away with emotion, the Waikiki members had a feeling that something important was about to happen. In the truck the old boards bumped together as if creating an air of expectation. “Thirty miles further south!” exclaimed the Gringo.

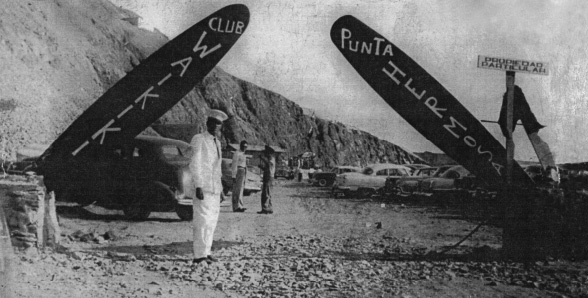

After two hours they came to a small fishing village surrounded by cliffs. I was called Punta Hermosa. Standing by the side of the road the surfers gazed towards where McNicholls was pointing. Elegant lines of swell swept through the bay. In those days Punta Hermosa was far from the popular beach resort that it is today. Except for a few shacks used by the fishermen there wasn’t a single house in town. There wasn’t even a dirt road for the surfers to access the bay. “How in the world do we get our boards down there?” asked someone. Pitty Block, with the help of two of the caddies, threw one of the boards down the cliff. The heavy wooden board slid down the sandy hillside and ended up down at the beach without any major mishap. The rest followed his lead, and soon all of the wooden boards were sliding down the hill. In all of the excitement, the Gringo disregarded what little Spanish he knew and started babbling in English in a lively manner. The only words the Peruvians could make out were words like “Makaha,” “giant waves” and “big surf.”

With their boards safely on the beach the crew of surfers was finally ready to head out to Punta Hermosa for the first time. A spirit of camaraderie kicked in, which was frankly always the case with the founders of the Waikiki Club. The waves were breaking far away from the shore, but they were all great paddlers and an inevitable competition commenced to who could be the first one to reach the lineup and catch one of the immense waves.

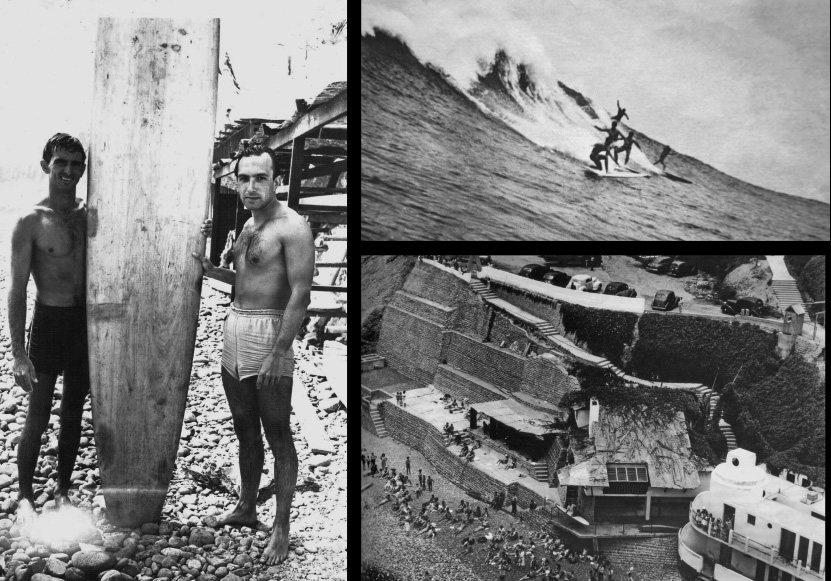

Even though they only had the heavy, primitive surfboards of the ‘40s, sometimes weighing as much as180 to 200 pounds, the Waikiki members paddled with all their might. Getting closer and closer to the great waves that, from their perspective, looked like they were going to swallow them whole, by the time they finally they reached the lineup the sea had somewhat calmed down. A long lull between sets gave them a chance to position themselves further out in the water. Dogny had already taken the lead and assumed the role of the surfer that would catch the first wave when the first set of waves began to roll in. A mountain-sized mass of water that at one point seemed to block out the sky loomed over him. With not other choice but to go, Dogny caught the great wave, made the drop and rode it successfully all the way through. The limited mobility and extreme weight of the board made the feat extremely dangerous. It’s said that when Dogny reached the shore he said, “One cannot surf these waves.”

The first set of waves literally swept them all off their feet, including Hall McNicholls. However, the eagerness and enthusiasm to dominate the savage surf weighed heavier than the risks and this early pioneers happily put life and limb on the line, all in an effort to eventually master the wave at Punta Hermosa.

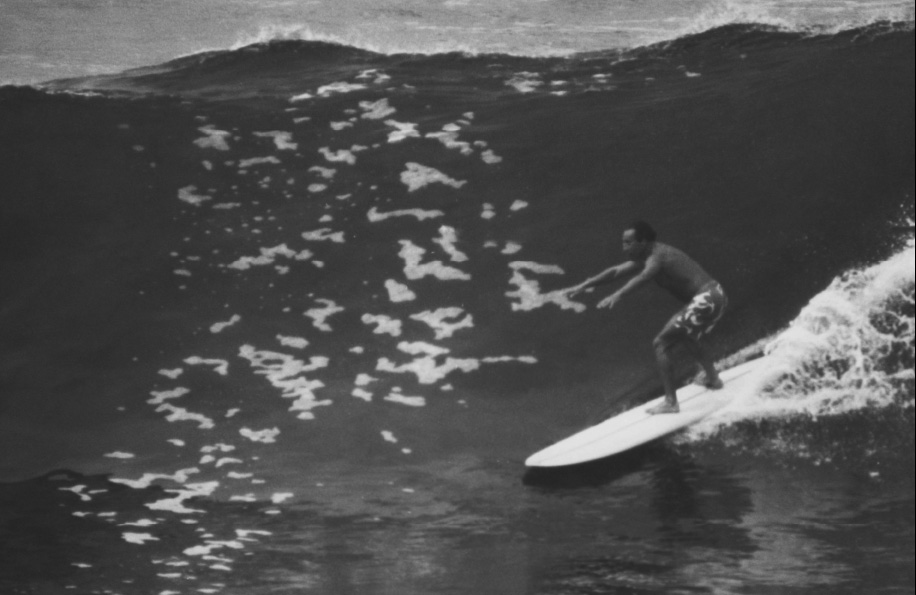

During the summer of 1954, Hawaiian George Downing visited the Peruvian beaches for the first time. The Waikiki Club, in a conscious move to further the evolution of their favorite sport, had reached out to The Outrigger Canoe Club of Hawaii, asking them to send their best instructor to teach them. Downing had just won an important tournament at Makaha, and was unanimously appointed by the Outrigger members to represent the Hawaiians in Peru. Even today, the surfers of that era remember with admiration Downing’s bold maneuvers as he, equipped with a light balsa wood board covered in fiberglass, rode the Kon Tiki waves with ease.

From the moment he arrived in Peru, Downing spent hours and hours in the Miraflores surf. Getting the most out of the waves, he showed off his full arsenal of maneuvers. For starters, Downing demonstrated the fundamentals of modern surfing to the Waikiki members. He showed them how to surf sideways on the wave. The Peruvian surfers watched in amazement as Downing made the drop on the Miraflores waves, leaning from one side to the other, working with the rails of the board, making turns up and down to quickly change direction and speed. Up until this point the club members had generally surfed the waves straight in to shore. What Downing was doing was revolutionary. The way he managed to paint the waves with moves and tricks had never even occurred to the guys from Miraflores.

Downing’s board, besides from being made out of balsa wood, also had a fin that helped him turn the board with ease and control. Besides just illustrating a more creative way to ride the waves, the equipment he brought with him from Hawaii would also have a lasting impact.

After surfing Miraflores for some time Downing was curious if there were other, bugger waves in the area that he could surf. The members of Club Waikiki looked at each other and collectively thought of their improvised surf trip the previous year to the beach that McNicholls had discovered. The following day, Downing found himself on the beach at Punta Hermosa. He was about to tempt fate in the same waves that had left Pancho Wiese, Eduardo Arena and Pitty Block in a cold sweat. With a smile of great satisfaction on his face, as if he had returned home to Hawaiian waters, Downing paddled out and ended up surfing more than a dozen waves by day’s end.

The Waikiki members could not believe their eyes. Without the 130 pounds of extra weight, Downing could do whatever he wanted on his light, balsa board. The members felt like they were watching a completely different sport than the one they had been practicing. On the beach, waiting for Downing to get out of the water, was Guillermo “Pancho” Wiese, eager to ask him if he would lend him the board. With the last rays of sunshine, Pancho Wiese went out, determined to once and for all master the immense waves that already had become legendary amongst the surfers.

He got on the board and immediately felt its buoyancy. With what seemed like only a few paddle strokes he reached the lineup. Once in open water he positioned himself and waited. The Waikiki members watched in anticipation. Pancho paddled. At the most critical point of the breaking wave he managed a dizzying ten-foot drop. Standing up on the light board, Pancho reached the bottom and leaned his body to one side. Angling the board with exceptional skill, the speed of the board allowed Wiese to stay ahead of the wave unscathed as it was chasing behind him. He rode the wave for almost 200 yards, feeling pure adrenaline and joy. He reached the shore with a gigantic smile running ear to ear. It was a gift that surfing would ever grant him for the rest of his life.

One of the most glorious days of Wiese’s life, from that point on he would embark on a career that would make him one of the foremost big wave surfers in the world. A couple of days later, as Downing was about to leave Lima to return to the island, Wiese paid the extravagant sum of 120 soles for his board. A couple of months later, Wiese was invited to participate in a surf competition in Makaha, thus becoming the first Peruvian surfer to represent his country at an international surf event. Due to his prior experience with the waves of Kon Tiki, the Peruvian big wave champion managed to finish fifth at Makaha.

In the winter of ’54, a shipment of ten new Hobie surfboards landed in Peru. Purchased by Eduardo Arena in California, much like Downing’s board these were made of balsa wood and had a fin fiberglassed into the tail to help with maneuverability. The heavy cedar boards that the Waikiki Club members had been riding were immediately put in storage.

Downing had also taught the Peruvians all about the different competitions that were held in Hawaii at that time, which is how they came to find out about long distance paddle races, relay races and the short distance speed races. Armed with reams of new information and knowledge courtesy their Hawaiian friend, as well as an arsenal of new boards, the Peruvian surfers now had all of the pieces in place to hold their first national surf championships in 1954. The first international championship would come the following year in 1955.

Ever since the legendary trip to explore the break that would come to be known as Kon Tiki, the Peruvian surfers knew that there was a powerful and fierce wave waiting for them at Punta Hermosa. Three friends became obsessed with the idea of mastering this wave: Guillermo “Pancho” Wiese, Eduardo Arena and Federico “Pitty” Block. They called themselves “The Three Musketeers,” a direct reference to the fictional characters created by author Alexandre Dumas. They were determined to master the wave at Kon Tiki at any cost.

Eventually their habit of going to Kon Tiki on a regular basis rubbed off on the rest of the members of the Waikiki Club. Led by Carlos Dogny, every weekend they would go in a great group and surf and have cocktail parties on the beach.

In the magazine published by the Waikiki Club in 1967 to celebrate their 25th anniversary there is a juicy chronicle written by Carlos Rey y Lama about the nature of these early sessions at Kon Tiki:

“One needs to consider how these first sessions on the open water were, and that the noise of the great waves, the wind, and the enormous quantity of water brought by each wave, inspired respect. The transportation of the boards was a feat itself, and even though the boards where nearly indestructible, each and every surfer were meticulous about having their boards in immaculate shape, especially the ‘peg’ which is the nautical term of the bronze plug located in the stern, and the ‘eyebolt,’ the bronze handle that each and every board was equipped with. The peg was there so one could drain out the water that inevitably would enter the board after a while, and the handle served the purpose of grabbing on to the board with both hands, using your whole body weight to avoid that the current carried your board three or four hundred yards away, which often happened.”

The Club decided to extend their facilities to the beaches south of Lima, allowing the surfers to frequently try bigger and stronger waves. Thanks to the acquisition of land right by the Kon Tiki point, they were able to organize the first international tournaments in Peru, which served as an introduction of the Peruvian champions to the rest of the surfing world.

So what happened to The Three Musketeers? They became the owners and masters of Kon Tiki. By surfing with the light boards that Arena had brought with him from California, they were able to capitalize on the incredible aquatic resources at their disposal. In the summers of 1952 and 1953, Al Dowden, a well-known surfer member of the San Onofre Surf Club in California, had come down for a visit. Back at home he’d learned that Peru had great, uncrowded waves and he decided to pay the country a visit. He was welcomed by the Waikiki Club members and was soon a habitué of the Lima beaches. Surfing the waves with a new and improved surfboard that made the Waikiki surfers realize that their old boards were practically useless by now. Dowden had invited Arena to come and visit the California surf club with the specific purpose of lining him up with some new boards. Arena’s visit had been postponed to June 1954, but upon his return to Peru all of the Waikiki Club Members were able to acquire their very own Hobie balsa wood surfboards with fins.

The first official competition in big waves surf happened at point Kon Tiki on Sunday, March 27, 1955. Monitored and evaluated by judges, it was the first national surf championship in Peru. Morning fog blanketed the beach, but the waves announced their presence with a roaring crash. The sea was barely visible and whitewater raged in the impact zone, giving the surfers a mere hint of how rough Kon Tiki was this day. The surfers were nervous and made the sign of the cross before paddling out. The competitors included Eduardo Arena, Alfredo “Pecho” Granda, Guillermo “Pancho” Wiese and Federico “Pitty” Block. The judges were Alfredo Álvarez Calderón, Richard Fernandini and Carlos Rey y Lama, the legendary “Rex.”

The ocean inspired such a respect amongst the surfers that they decided to paddle out wearing life jackets. Little did they realized that if a wave had brought them down the life jackets would have them helped drag them hundreds of yards with the very real risk of drowning in the process. The waves were bigger than anyone had ever seen them, and despite the immense respect given to the ocean, both the competitors and judges entered the water. The judges had clipboard-like devices attached on the deck of their boards’ noses with two colored pens dangling from their necks. The surf was a consistent 20-foot all morning, and while the surfers were used to the conditions at Kon Tiki, they had never before seen it break with such raw power. According to Carlos Rey y Lama the swell literally swept away the bay.

“It was the first time we had ever seen the ocean that way, forming into one single mountain-like wave that rose up all the way from Kon Tiki to the island of Punta Hermosa,” recalls Rey y Lama. “We did not realize this until we were up close and the fog had dispersed, looking for the ‘calm channel’ of more appeased water, only to discover that there was no such thing where we could pass thru the waves. The competitors were struggling with catching the waves, and the breaking point kept changing positions, sometimes further out, other times further in, always breaking with great force only moments after the wave formed.”

After a long struggle to make it outside the turbulent waves, both the competitors and judges finally reached the lineup. The first one to catch a wave was Alfredo Granda, known as Pecho, who unlike his rivals who were surfing with modern balsawood boards, had entered with one of the large boards of the ‘40s. Encouraged by his success, the young Pitty Block caught the second wave, followed by Eduardo Arena and Pancho Wiese. The judges, sitting on their boards, scored based on three criteria: the size of the wave, the difficulty of the wave, and the distance surfed.

Guillermo “Pancho” Wiese took the early lead and looked like a shoo-in to win when the great Pecho Granda caught a gigantic, heaven-sent wave. The biggest wave of the whole morning, he made the drop with his life jacket wrapped around his neck. Crouched in a deep, low stance he practically plastered himself to the board. The wave crashed down around him, foam swallowing him in one gulp. Miraculously Pecho managed to emerge from the whitewater intact, standing firmly on his board. After having surfed almost two hundred yards he kicked out. This was the birth of the national big wave championships and Alfredo Granda was its first champion.

The first surf competitions that were organized in Peru followed the rules shared by George Downing and included, on top of the actual surf competition, various disciplines to measure the strength, stamina and capability of the competitors. These championships were looking to establish an evaluation system that allowed the judges to crown their champion based on the total summation of points that they accumulated over the course of the different events.

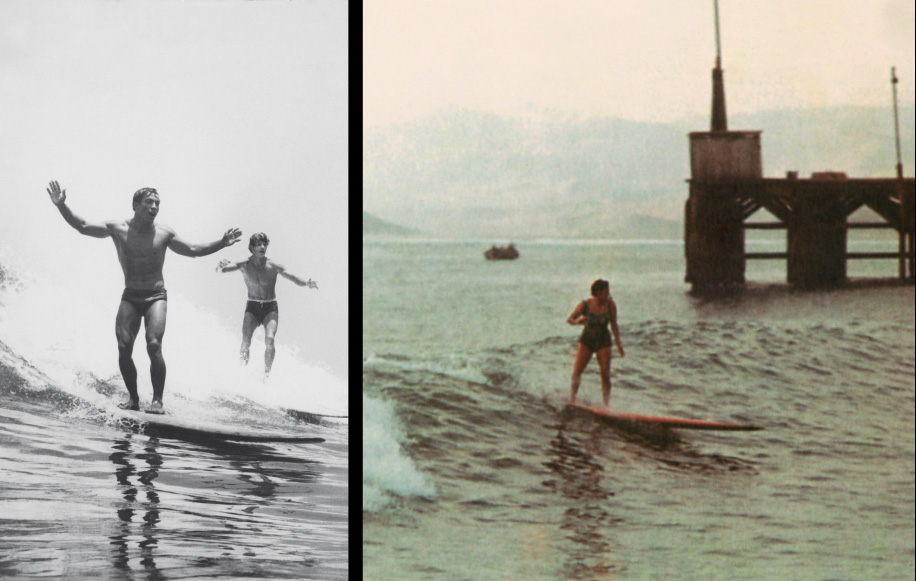

The events ranged from long distance races between La Herradura and Waikiki, where the surfers had to paddle a distance of over five nautical miles (about six miles) on their surfboards, challenging currents and swells. There were also sprints, which combined the best results of the distances 2000, 1000, 500 and 300 meters (approximately 1.25 miles, 0.61 miles, a bit over 500 yards and 300 yards, respectively). There was a surf mat event for women. And the graceful tandem sessions showcased the elegance of couples maneuvering in the surf. All of these events were integral components of the competition. However, the final test, saved for last, was the big wave surf competition at Kon Tiki. In this instance competitors were judged on four accounts: The size of the wave, the position of the surfer in relation to the critical point of the wave, speed, and finally the length of ride. Winning the last event did not guarantee one would be crowned champion, rather the competition looked to find and reward the surfer who combined the best of all these disciplines. The champions of these tournaments had to be multi-faceted, great athletes and soon they gained in popularity, leading one newspaper of the time to write that “in Waikiki there are more competitions than at the racetracks.”

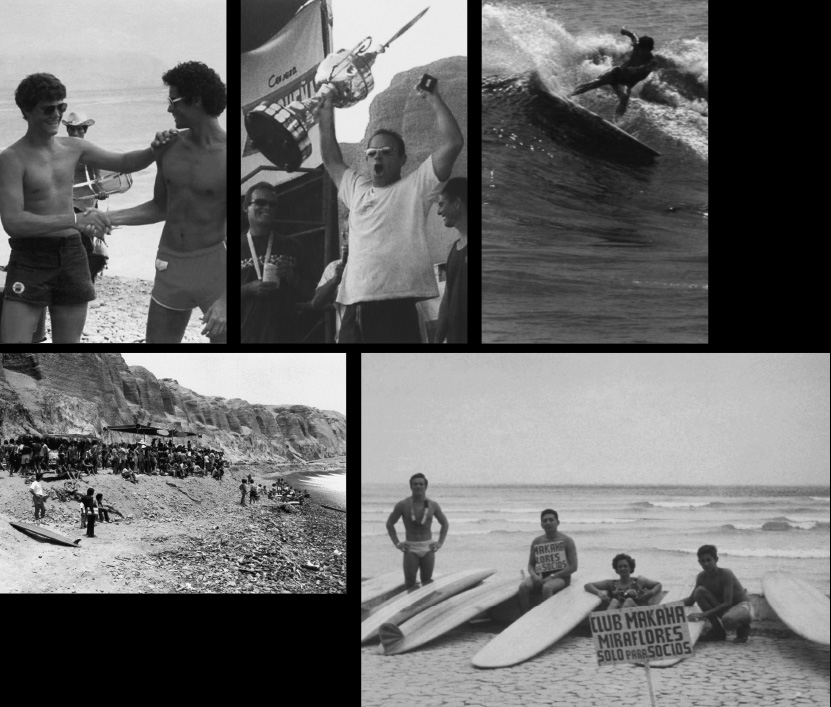

In 1956 the first international championship took place in Peru. The Peruvian team, led by Eduardo Arena, Guillermo Wiese, Alfredo Granda, Augusto Felipe Wiese, Fernando Arrarte and Federico “Pitty” Block, came in as favorites due to their superior knowledge of the waves. But representing the United States powerhouse was the San Onofre Surf Club from California. While Albert Dowden, the president of the San Onofre club, accumulated the most points in the different disciplines (long distance paddle, speed etc.), once the surfers reached the Kon Tiki break for the final event—big wave surfing—Arena dominated the event completely and became the first Peruvian international champion of big wave surf.

The second international surf championship was organized in 1957 and was attended by a Hawaiian team that included the famous Conrad Cunha, the first female champion Ethel Kukea, Albert “Rabbit” Kekai and Roy Ichinose, all of them members of the Hawaiian National Team. Perhaps the most significant part of the championship was that, while the Peruvians had previously been using balsawood boards, they were able to pick up smaller, lighter foam and fiberglass boards that Cunha and Kekai left behind them. Thanks to the international exchange between surfers the Peruvians technology and prowess in the water had increased considerably, which would eventually turn the Peruvian team into a feared opponent in championships to come.

Peru California Peru Hawaii

Eduardo Arena Albert Dowden Eduardo Arena “Rabbit” Kekai

Augusto Felipe Wiese Tom Wilson Dennis Gonzáles Conrad Cunha

Fernando Arrarte Richard De Witt Héctor Velarde Robert Ichinose

Federico Block Robert Silver Augusto F. Wiese Ethel Kukea

Felipe de Osma Reinz Wunderlick Guillermo Wiese

Ramón Raguz Federico Block

Rafael Navarro Fernando Arrarte

Alfredo Granda Alfredo Hohaguen

Richard Fernandini Oscar Berckemeyer

Herbert Mulanovich

Alfredo Hohaguen

1. Alberto Dowden (California, USA) 32 Points

2. Eduardo Arena 20

Augusto Felipe Wiese 8

Fernando Arrarte 8

Federico Block 8

Robert Silver (California, USA) 4

Federico de Osma 3

Ramón Raguz 2

Rafael Navarro 2

Alfredo Granda 1

EQUIPO PERUANO EQUIPO HAWAIANO

Eduardo Arena Rabbit Kekai

Dennis Gonzáles Conrad Cunha

Héctor Velarde Robert Ichinose

Augusto Felipe Wiese Ethel Kukea

Guillermo Wiese

Federico Block

Fernando Arrarte

Alfredo Hohaguen

Oscar Berckemeyer

Guillermo Wiese 1. Conrad Cunha (Hawaii) 12 Points

Armando Vignali 2. Guillermo Wiese 8

Dennis Gonzáles 3. Federico Block 6

4. “Rabbit” Kekai (Hawaii) 4

5. Eduardo Arena 4

6. Augusto Felipe Wiese 4

Thanks to friendships struck up during the second international competition a group of Peruvians was invited by the Outrigger Canoe Club of Honolulu to come visit Hawaii in 1959. Carlos Rey y Lama, Richard Fernandini, Federico “Pitty” Block and Fernando “Pollo” Arrarte jumped at the opportunity to represent Peru in Hawaii. The Hawaiians took it upon themselves and organized a competition at Waikiki on July 12. The events included a long distance paddle, where Arrarte earned himself a fifth place, as well as sprints, where Fernando snagged the second place and Rey y Lama ended in fourth place. There was also the surfing competition in which Block was the strongest Peruvian surfer. John Lynn and the legendary Duke Kahanamoku dominated the championship. The Peruvian team’s efforts were commended and applauded by the Hawaiians, who were fascinated by the fact that the regal sport had spread across the world.

The adventurous and cosmopolitan life of Carlos Dogny Larco was not only instrumental in laying the groundwork for surfing in Peru, but it also led to the foundation of the first surf club in European waters. During a trip to France in 1959 he brought his surfboard along with him to put on a demonstration at the beach in Biarritz. The nobility of Europe, who happened to be spending their summer vacations in the exclusive resort town in the southwest of France, were amazed when they witnessed a man riding the waves on a long board. The youngsters of the beach immediately gave Dogny a warm and enthusiastic welcome and Dogny decided to found an extension of the Waikiki Club in Biarritz. By then, Peru was a force to be reckoned with in the international world of surfing and the members of Waikiki Club were ultimately responsible for helping spread the sport in Europe and throughout South America.

An important part of a surfer’s life is their readiness to rescue people from drowning. However, what happened to the guys at Waikiki Club in 1959 went beyond that and could easily have served as the script for an action movie. According to an article published in the newspaper El Comercio, Richard Fernandini spotted an air force squadron at around 12:45 pm flying from north to south across the sky of Miraflores. Fernandini was sure that they would keep their course and soon disappear behind the mountains of Chorrillos. Suddenly as one of the planes was flying past La Pampilla it dropped a piece of machinery in the water. The plane began to lose altitude. It passed over the clubhouse at a height of 300 feet, and right around the Armendáriz Gorge it leveled with the ocean. Fernandini and his friends thought that they were witnessing a reckless air acrobatics stunt when they the plane bounce off the water. As it started to sink they grabbed four boards jumped into Alfredo Payet’s car and set off towards the surf break.

Accompanied by Alfredo Hohagen and Federico “Pitty” Block, Fernandini and Payet got on their boards and paddled the two thirds of a mile out to sea to the plane. In only five minutes after the accident happened they reached the pilot. The surfers found him floating unconscious and they laid him on his back across three of their boards. They took turns swimming towards shore. About halfway in they picked up two exhausted swimmers who had been trying to reach the accident. One on the beach they applied first aid and managed to revive the pilot. A second lieutenant of the Peruvian Air Force named Manuel Montenegro, he later confirmed that his P-47 had run out of fuel. After having saved the life of the pilot and the two impromptu lifeguards, the four friends returned to the Waikiki Club, proud of their good deeds and quite conscious of their responsibility as potential lifeguards.

La Asociación Pacífico Sur (The South Pacific Association) was founded on October 7, 1959, with the aim to establish the Club Pacífico Sur (South Pacific Club) and to promote surfing. With this in mind a group of young college friends living in the same neighborhood in San Isidro, Lima requested, and were granted, a plot of land close to the Waikiki Club, at the oceanfront of Miraflores Costa Verde. There they started building a terrace, two bathrooms and a storage room for their surfboards. The founders, as noted down in their constitution, were César Belaúnde, Joe Carrillo, Álvaro García Sayán, Jorge De Romaña, and César Belaúnde, who served as the first club president. In the beginning the members of the club were a generation younger than the members of the Waikiki Club, and the ambiance of the club was sporty and welcoming. Today this club keeps promoting the sport of surfing through their participation as co-founder of the Federación Deportiva Nacional de Tabla (Surfing National Federation) and it is club policy to offer membership privileges to some of the most outstanding young surfers, who become Sport Members of the club.

As the club evolved its role in Peruvian surfing, they eventually founded the club the first ever version of the José Duany championship, in honor of the deceased club member of the same name. In 1970 club president Mario Suito Sueyras helped organize what would become an annual event for more than 30 years at La Pampilla and Miraflores. Over time it established itself as the most important national competition in small surf. It became a steppingstone for competitors and future champions as it was designed as an open championship with multiple categories. The winners of each category would face off in a final round, thus giving underdogs great opportunities to excel and shine. This has been the case with Brad Waller, Carlos Espejo, Max and “Magoo” De La Rosa, “Makki” Block, Luiggi Nikaido, Gabriel Villarán, Roberto Meza, Juan Manuel Zegarra, Milton Whilar, and many more.

The José Duany championship kept going until 2002. Luis Miguel De La Rosa Toro, known as Magoo, managed to secure the South Pacific Cup by fulfilling one of the two requirements: he won the Open category a total of five times. The other way to secure the cup was to win the championship three consecutive years, which was nearly accomplished by Sergio Barreda and Gabriel Gómez Sánchez, for example. The competition would generally attract 150 competitors in all its different categories, and some years over 200 surfers participated. Until its final year, this championship was one of the obligatory competitions of the Peruvian National Surf Circuit.

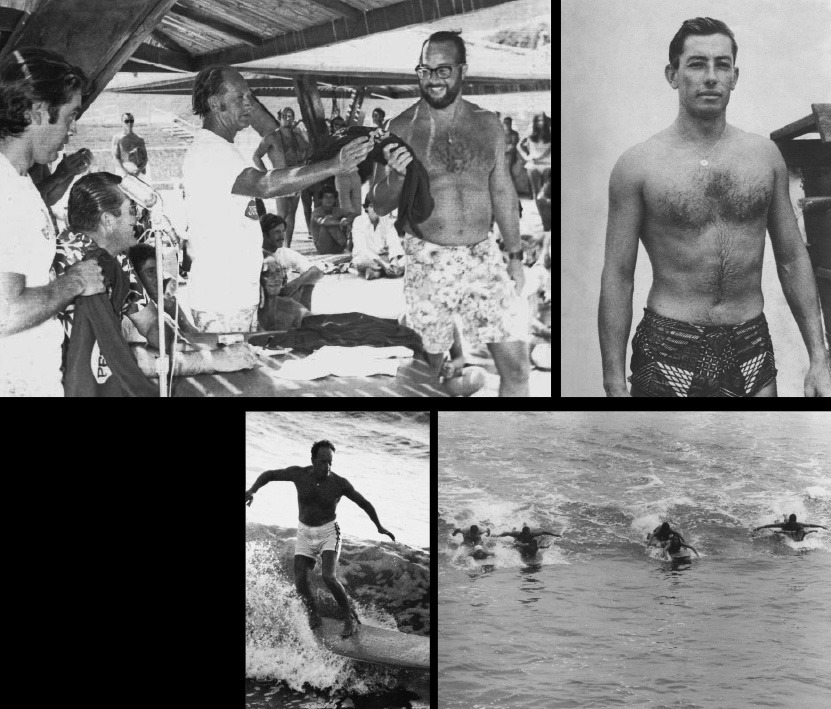

It was a group of surfers from Miraflores that eventually decided to found the famous Makaha Club. Their provisional facilities were at Inclán street and founding members include Luis Arguedas Gonzáles, Carlos Kruguer, Pedro Zavala, Julio Ratto, Juan Larrañaga, Jorge Pautrat, Carlos Barreda, Miguel Pujazón, Luis Caballero, Guillermo Arguedas, Armín Zettel, Alfredo Segovia, Santiago Patroni, Germán Merino, Augusto López, Carlos Pestana, César Pastor, Alfredo Román, Luis Claux, Pedro Muñoz, José Raygada, Carlos Prieto, Federico Blume, Humberto Lazarte and Humberto Patroni.

The young club members used to hang out under a palm tree on the beach at Miraflores and they soon became friends with the members of the Waikiki Club. One of these members, César Barrios, saw how these youngsters yearned to have a club of their own and generously helped the members of Makaha Club finance the construction of their own facilities. The construction of the Makaha Club was quite different from that of Waikiki Club. Since they did not have the financial means of their neighbors they built the clubhouse themselves. Among the young construction workers was Sonia Barreda (who was to become Peru’s national surf champion), who carried bricks, mixed cement, moved rocks and built walls along with the rest of the new club members. Finally they had their own clubhouse, and their first surf instructor was none other than Carlos Dogny Larco himself.

The official founding date of the Makaha Club was October 12, 1959. They would soon outpace other clubs because of the daring and courageous surfing of many of its members. Sonia Barreda, alongside with her sons Sergio and Carlos, the unforgettable Eve Eyzaguirre, Raúl “Wantan” Risso and the beautiful Pilar Merino and Carmen Pastorelli were individuals who stood out in this new era of surfing. Other well-known members included Oscar Malpartida, Pocho Awapara, Iván and Erik Sardá, Ivo and the “Gringo” Hanza, Ricardo Bouroncle, Fernando Ortiz de Zevallos, Rodolfo Valdez and Toto Gallo. Two years later, in 1961, the Makaha Club would grow even stronger as they joined forces with the Club Topanga of Barranco.