“…there were many of them, each and every one on their own reed raft, like stubborn horse riders, slicing the waves of the sea, and it is rough there where they fish, looking likes tritons or neptunes painted over the water…”

Fray José de Acosta

Historia Natural y Moral de las Indias

1550

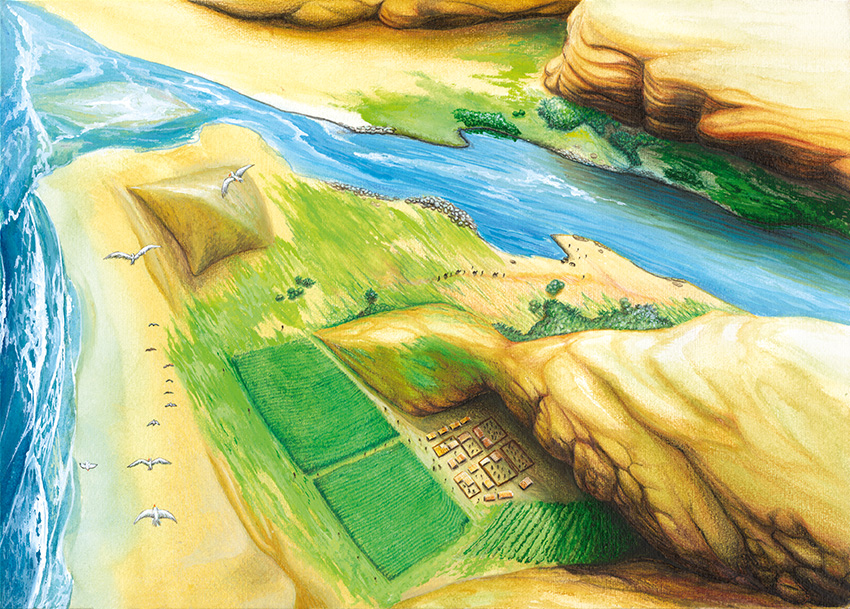

Imagine being seated comfortably in a movie theater in front of a gigantic screen. The camera pans from the stratosphere and carries you like a condor through the central Andes, gliding down toward the Peruvian coast. Terraces on the slopes of the mountains are being cultivated by the people of the pre-Columbian communities that, dressed in festive, multicolor costumes, offer their harvest to their gods with elaborated rituals.

The camera continues to soar, descending vertiginously through a gorge that divides the mountains until it tappers off into the desert. You keep flying over muleteers, shepherds and merchants with a llama and vicuña (a Peruvian camelid) caravan, carrying fish and seafood back to the highlands. A mighty river flows and nearby crops feed the population of the valley. Fishing lagoons, swampy lands where bulrush and totora reed grow and thick carob tree forests precede the appearance of the first salt marshes where Yunga women diligently salt-cure big fishes.

A sandstorm whistles near the doorsteps of a huaca (Quechua for temple) that’s been consecrated to Pachacamac (Quechua for the Earth Creator God). The camera slows down, focusing its magical time machine view on a small fishing village. There is a bustle of activity as the camera flies over a group of children, dressed in fine garments, running to the shore where Kimu, the young Yunga fisherman, is ready to go out fishing for the first time.

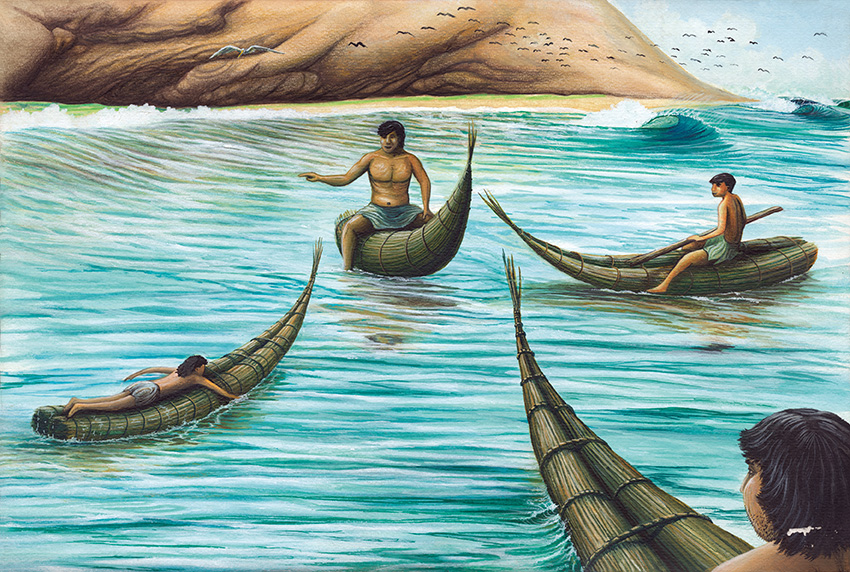

The bare and polished upper body of Kimu attracts the attention of the young girls of the fishing village. He scrutinizes the waves and the fleet of small rafts with triangular sails right beyond the waves. Kimu is only twelve years old and is about to start his life as a fisherman.

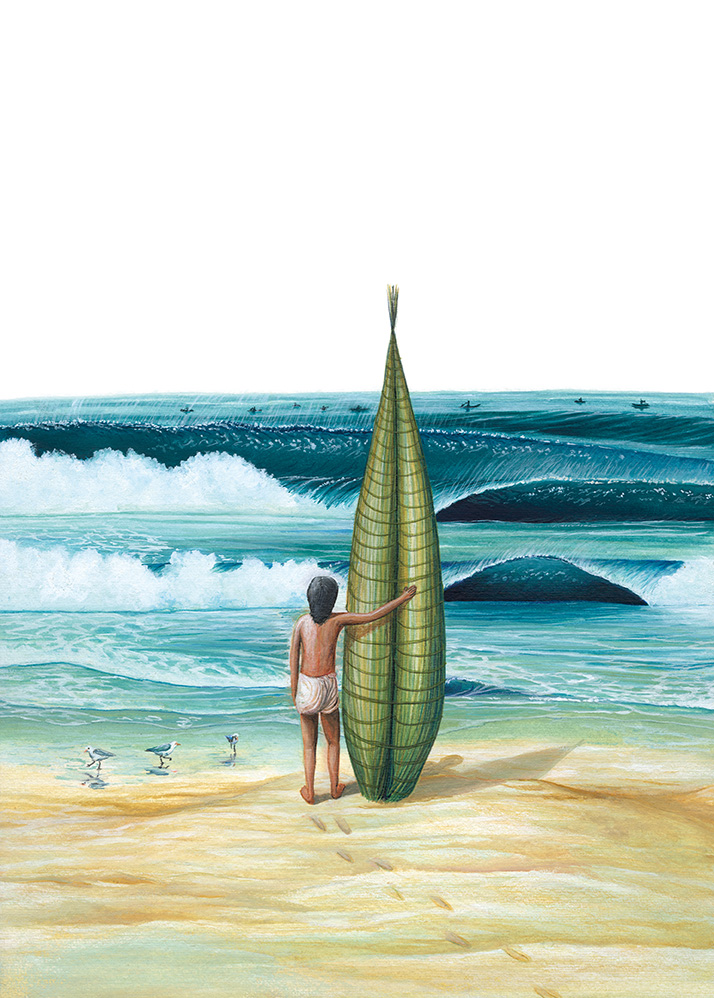

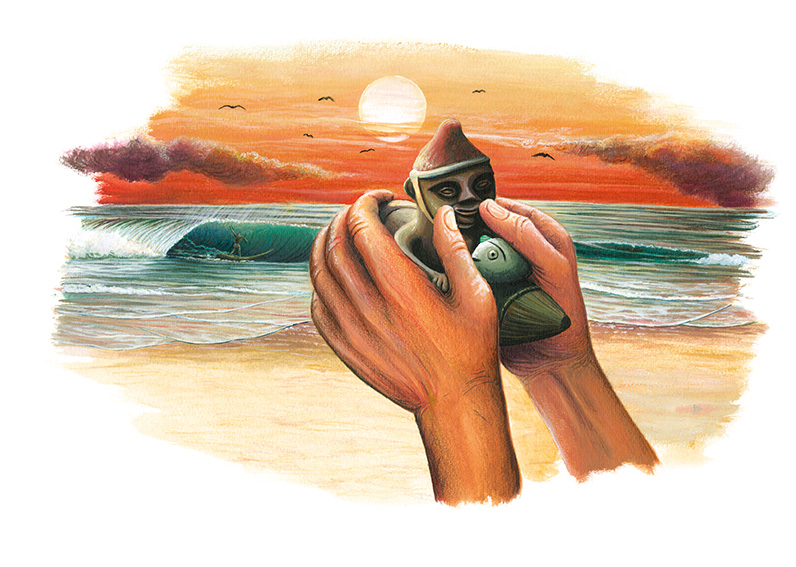

Since he can remember, Kimu’s held a fascination for the ever-changing and endless ocean that feeds his family. But now his time playing on the shore with seashells is over. Now he knows, from the bottom of his soul, that he needs to learn all about fishing to support his family. Kimu and his father have harvested totora reeds from a nearby marsh. They’ve fashioned the reeds into a tup (one-man reed raft). If you just glanced at his craft you would recognize it as a caballito de totora from Huanchaco.

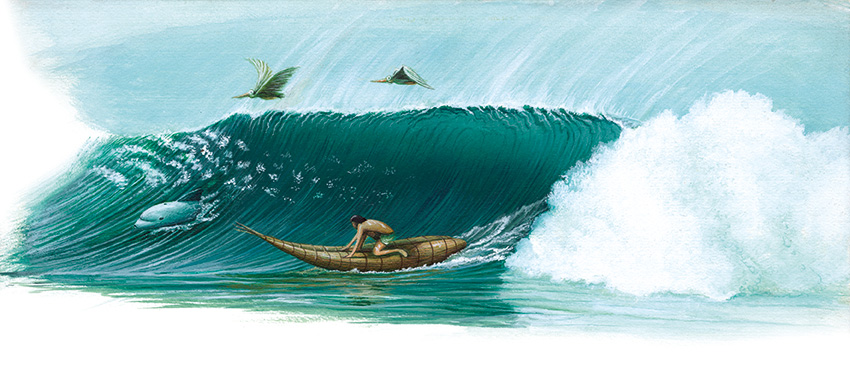

Standing on the shore facing the ocean, waiting for the right moment paddle out, Kimu carries his tup like a modern surfboard. For a brief moment the waves stop crashing and Kimu, agile like a puma, springs atop his tup. He starts paddling fiercely, knowing that he needs to get out beyond the waves before a next set comes in. The waves represent the energy and movement of the ocean and since time began they’ve been part of the iconography represented on the pottery of the people of his fishing village.

While paddling tirelessly, Kimu ponders if waves are barriers built by the ocean to prevent people to come into its domains and steal its fishes. For that reason, Kimu’s father has shaped the tip of his tup slightly curved up so he can go over the waves with ease. Far off, behind the waves, the fishermen notice Kimu’s effort and begin to cheer him on. Encouraged by the shouting of the fishermen and by the chorus of the children on the shore cheering, Kimu finds added strength to continue paddling. While watching the waves from the edge of the shore, Kimu experienced fear, but now as he looks up at them from sea level it turns to terror. The giant swells look like sea monsters, rising unexpectedly, trying to swallow him and push him down to the domain of the sacred shell Mullu (Quechua word for Spondylus.)

Suddenly an enormous wave stands up in front of him. It blocks the horizon, hiding the fishermen on the outer waters. It is Kimu’s moment of truth—the moment that his father talked about so many times. He makes a supreme effort and paddles furiously toward the wave. The swell surges, blocking out the clouds. The powerful lip throws over. Kimu hears a thunderous crash. The cascading wave forms a blue, tubular cavern, like huge jaws wanting to eat him alive. Kimu manages to dodge the wave, barely surviving.

For a moment, Kimu spies the fishermen, far from the waves, staring at him. Then he feels an explosion coming from the back, as if the whole force of the ocean is being released behind him. Kimu is captivated by the rainbow that is formed by the droplets of water surrounding him. He pauses, hoping that the danger is over, but shouting from the fishermen indicate there are more waves coming. The next wave in the set is even bigger, and for a second, while he is riding on top of the wave, he looks down at the fishermen who are waving, shouting and encouraging him to keep going. Kimu hears another thunderous explosion, but now he knows what is going on and he enjoys the ride.

The ocean gives Kimu a break. The calm allows him to collect himself and calmly paddle to the other fishermen. They are sitting on top of their totora vessels, waiting for him with big smiles on their faces as they welcome him. Kimu returns their greeting with another smile. Then he finally places his tup next to his father’s. Amongst the group of men he spots his older brother, who only a couple of years earlier had begun his life as a fisherman, and the chief of the village, a stylish, middle-age Yunga man.

“Now you have go in,” said Kimu’s father.

“How?” asked the soon-to-be-fisherman.

“Riding a wave?” answered the chief of the fishing village.

Kimu had seen numerous times how the fishermen, coming in from the open ocean, reached the lineup and waited for a wave. Once the wave arrived, they paddled facing the shore, until the wave’s energy pulled the tup down. That was when the fishermen were able to ride the wave up to the very edge of the shore, finishing the ride with a big smile showing their satisfaction. Kimu had never understood how they could smile after riding these humongous and terrifying waves. He’d always assumed that the smile was due to their catch from the day.

“Don’t worry, Kimu, I will teach you how to do it,” said Huanchac, Kimu’s older brother, under the approving gaze of their father and the rest of the fishermen.

“Don’t be afraid,” added the chief of the village- You will like it.

Kimu, now puzzled, is unsure of how to respond to the chief’s challenge. He is still incapable of conceiving the pleasure of riding a wave. As he turns the tip of is tup, aiming to shore, he is sees the fishermen smiling. He can’t tell if they are being sarcastic or happy. Following Huanchac’s lead, Kimu starts paddling toward the shore, afraid of getting into the break zone. A pod of porpoises make their appearance and the fishermen greet the presence of the sacred animals as a good omen. Kimu feels his spirit being boosted by the presence of the ocean mammals and regains the courage to follow his brother.

“Brother,” Huanchac addressed Kimu, “before anything you need to dominate your fear. The only way to reach the beach is by catching a wave, in the same way as the fishermen do, and as you have seen them do this since we were kids. Look, there is the first one approaching us, pay attention on how it is done, and then you follow me.”

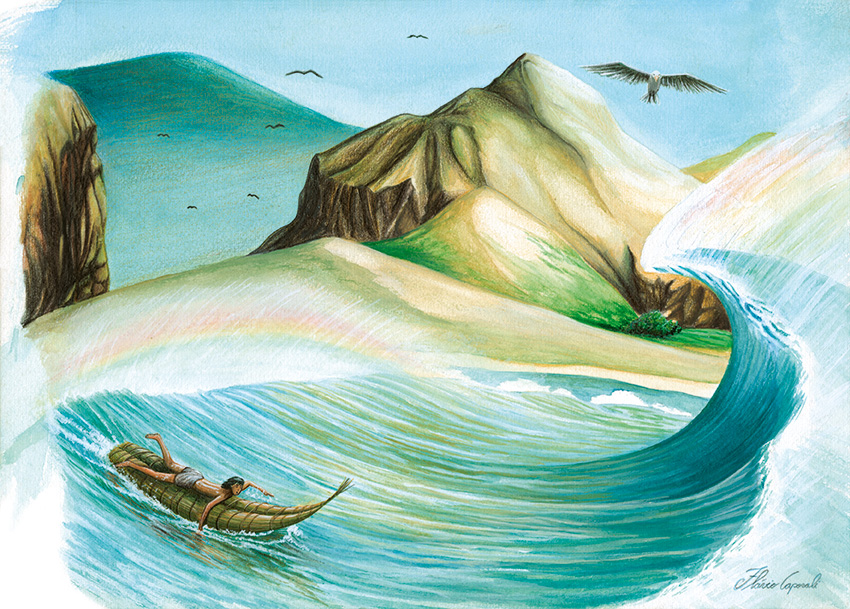

Huanchac lies down on his reed raft and starts to paddle toward the shore. The first wave of the set lifts Kimu up to the sky and from there he can clearly see how his brother is paddling until the force of the wave begins to drag his tup with great force. He disappears from view, screaming excitedly as he heads for the shore.

“Pachacamac!” invokes Kimu, “help me and I will make you an offering out of my first day of fishing.”

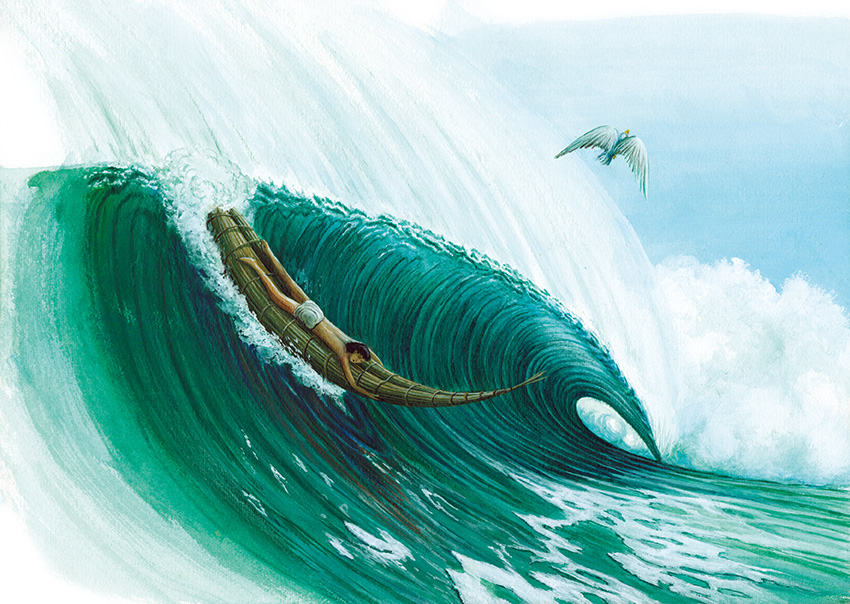

The second wave was not long in coming. From the crest of the wave, Kimu can make out his father smiling at him, which motivates him to paddle even harder than when he was coming out. The wave has already started to peel off and Kimu catches the wave before it swallows him up. He will never forget this moment. The tup made by his father holds nice and firm. He starts dropping into the wave Kimu. He experiences a free fall, reaching the bottom in no time. He is followed by a thunderous monster behind his back, the tup gains speed, transporting Kimu swiftly to the distant shore. Some time ago Kimu had dreamed about flying and he now relives his dream with amazing accuracy. The edges of his tup dip slightly underwater. Kimu cannot contain his happiness and start yelling.

“I’m flying Pachacamac, I’m flying, I’m flying!”

A flock of pelicans fly along with Kimu, playing with the wave. A porpoise joins the group, riding just a few inches apart from Kimu. The wind hits Kimu’s face, inviting him to smile, and the ocean responds to Kimu’s happiness by weaving an intricate tapestry on its whitewater. Kimu is having a blast and for an unknown reason decides to kneel on his tup. By doing so he notices how the ride becomes more harmonious and smooth, then he proceeds carefully to rise to his feet.

The fear is gone. Kimu’s self-confidence is sky high. He puts his hand in the water and his body leans dangerously, but is able to keep his balance and the tup races up to the middle of the wave. Suddenly the wave he is riding rises up. Kimu hunches down, squatting as low as he can. He finds himself inside a blue cave of water, and continues on the wave without being touched by the water. The ride lasts for a couple of seconds, but for Kimu it lasts a lifetime.

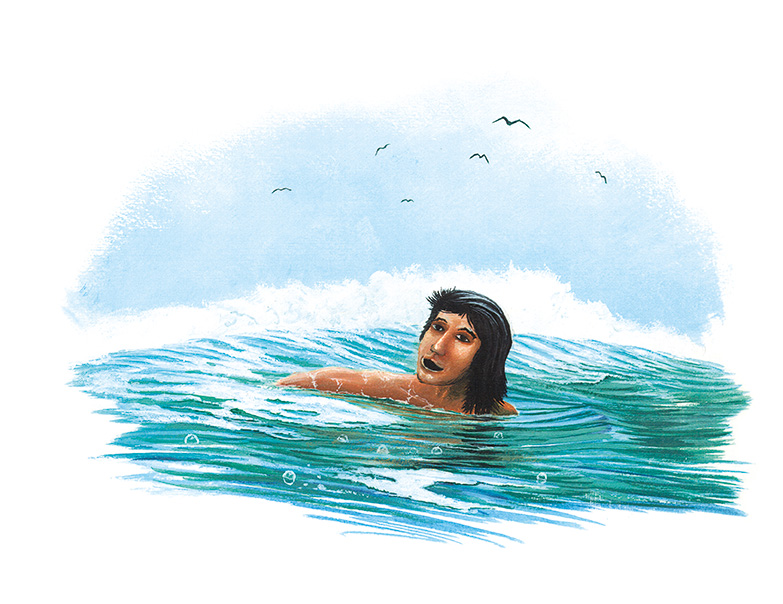

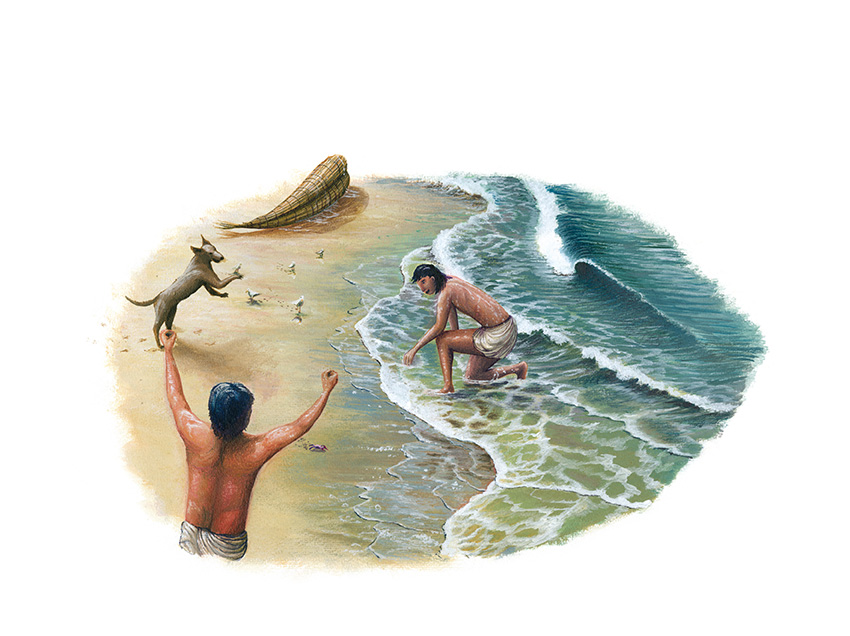

The rumbling of the wave vanishes and is followed by an almost divine silence just before Kimu goes down wrapped in an explosion of whitewater. He tumbles around for a few meters before emerging to catch a breath. His tup in on the shore where Huanchac, accompanied by women and children of the fishing village, are taking in the scene. Kimu swims to shore. His brother runs to hug him while the kids surround the brothers and start to chant Kimu’s name.

Kimu would never be the same. As time passed he became the most skillful fishermen. He would go out fishing with his brother, Huanchac, at night in the open sea only to come back into the bay at noon with their tups full of fish. He would then spend the rest of the day training children to deal with the waves, speeding up their fishing learning process, and when he had free time, he and his brother went searching for new beaches with good waves. Years later, his face was reproduced in numerous potteries, spreading the art of riding waves along the coastline. The ceramic artists used to paint him with a big smile, which archaeologists later would think of as the result of a bountiful fishing catch, when it was truly an expression of satisfaction after having caught a great wave.

The camera starts to zoom out and you see Kimu standing with his brother Huanchac, contemplating the waves as they continuously roll into shore, inviting them to ride on top of them, honoring their gods. The camera zooms out even further and the view widens, showing more beaches on the gigantic movie theater screen. In each and every beach you see a young fisherman dropping into a wave on top of his tup. At this moment, you unequivocally understand why Peruvians feel such pride when they learn that the art of riding waves was discovered by ancient Peruvian fishermen.

CHAPTER ONE: THE FISHERMEN SURFERS

CHAPTER TWO: NAVIGATION IN ANCIENT PERU

CHAPTER THREE: A PLAUSIBLE PERU-POLYNESIA CONNECTION

CHAPTER FOUR: THE HAWAIIAN TRADITION

CHAPTER FIVE: CARLOS DOGNY LARCO AND THE CLUB WAIKIKI (1938 - 1949)

CHAPTER SIX: THE FIRST YEARS WERE INSTITUTIONAL (1950 - 1959)

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE AMAZING DECADE (1960 - 1969)

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE RISE OF THE BROTHERS OF THE SEA (1970 - 1979)

CHAPTER NINE: EVOLVE WITH YOUR SPORT (1980 - 1989)

CHAPTER TEN: THE BEGINNING OF MODERN HISTORY (1990 - 1999)

CHAPTER ELEVEN: PERU: TOP LATIN AMERICAN SURFING POWER (2000 - 2009)