Since the dawn of Hawaiian culture, approximately the fourth century B.C.E., they lived in harmony with the ocean surrounding them. As they established themselves in the islands and their traditions flourished the art of surfing became a daily activity with great social reach. Men, women and children from all levels of society were drawn to and enjoyed the waves.

It is probable that the first Hawaiian surfers, just like the ancient Peruvians, discovered the pleasure of surfing on their own. Maybe they were fishermen who, used to the stresses of working at sea, found an elemental force capable of pushing their vessels to shore, and thus relieving some of their burden. It seems likely that had to be something in between the great outrigger canoes and the first primitive Hawaiian surfboards, a bridge or connection where people transitioned from sitting and riding in canoes as it related to work and standing up and gliding along for fun. It is possible that perhaps the Peruvian tup or caballito de totora potentially fills this void.

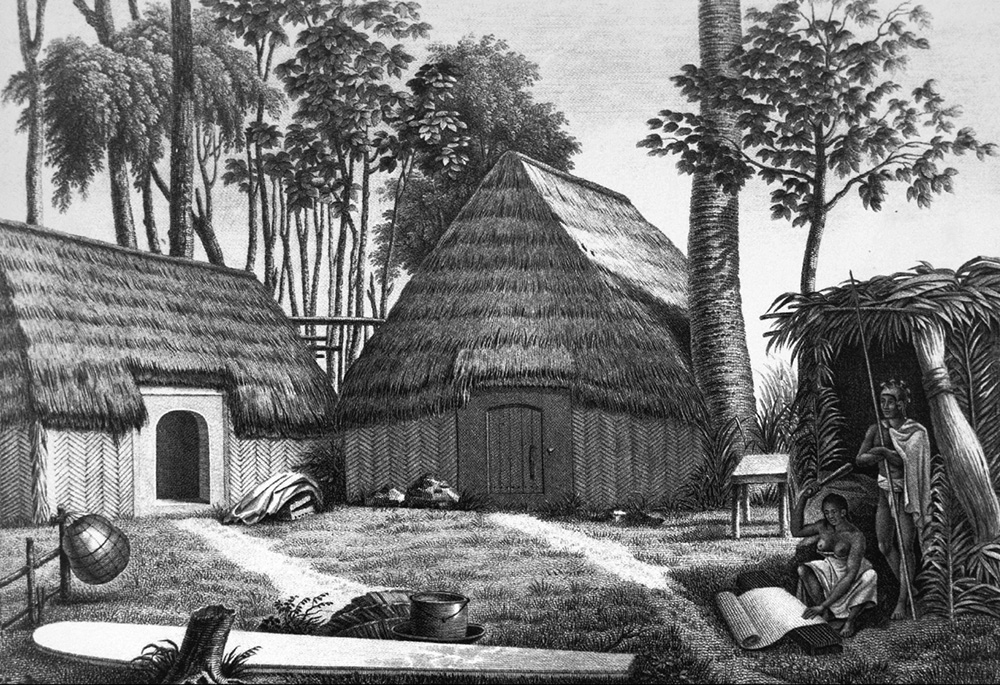

Much like their descendants, the Polynesians, the Hawaiians governed through a class and caste system. The governing class consisted of Hawaiians that possessed noble lineage or were related to the king himself. They ruled over the commoners, a class composed of the rest of the islanders. For centuries only the dominant class had the privilege to enjoy the most beautiful beaches with the best waves to practice the ritual of surfing. Furthermore, only they had access to the Kao and Wiliwili wood. The latter was lighter and floated better than the rest of the Hawaiian woods. It was used to build a bigger surfboard called “olo.” For these reasons surfing was considered the sport of kings and became a fundamental part of the Hawaiian royalties’ lives.

Liloa, the king of Hawaii, had traveled to Kokohalile to consecrate a temple, and after the ceremony he found the time to take a bath in a nearby stream. By the stream he met a beautiful local woman named Akahiakulana, with whom he was instantly infatuated. He seduced her, and when it was time to leave he asked her that if she was to become pregnant from their intimacy and give birth to a son to name him Umi and send the boy to him.

Akahiakulana did become pregnant and birthed a baby boy. Doing as she was instructed, she named him Umi. But she opted to raise the baby. Shortly after her meeting with the king, Akahiakulana had married another man, who abused her son. One day Akahiakulana had enough of Umi’s mistreatment and told everyone that he was actually was the son of the Great Chief Liloa and her husband had no rights concerning him.

She finally sent Umi to live with his real father, where he was received by King Liloa and his other son, Hakau—who was not happy with Umi’s arrival. The tension between the two half-brothers became known throughout the country, and upon King Liloa’s death, the heritage was split in two; Hakau was to rule all of the land, while Umi became the chief of temples and gods.

The people detested Hakau’s rule and clamored for Umi to rise as their one and only chief. They created an army to defeat Hakau, crowning Umi as king of all lands, temples and gods.

Before becoming the great Chief of Hawaii, Umi lived a simple life in Waipunalei with one of his followers, Koi, far from Hakau and his attempts to make his life miserable. One day Umi visited Laupahoehoe, one of the top beaches on the island, where he saw a surfer named Paiea surfing a wave not far away from they were standing. Umi heard the people speak in awe about the great skill of Paiea every time he rode one of the majestic waves. Being an excellent surfer with years of experience himself, Umi approached one of the admirers and asked, “Is that the best Paiea can do, just to rise up with the surf to fall back down again? That is not the way surf is ridden in our land. One must ride clear to the edge of the beach before he can be called an expert.”

It did not take long before Paiea became aware of Umi’s comments and confronted him. Umi did not bother to agree or disagree to having said anything, not giving much importance to the confrontation, which made Paiea furious. He challenged Umi to a surf competition, in which the loser would become the winner’s servant. Umi accepted, but Paiea´s pride was extremely hurt and he expanded the challenge to include two double and one single canoe in exchange for Umi’s whalebone necklace. Umi once again accepted. But Paiea was still not content. He raised the stakes further. He now wanted to bet four double canoes for the very bones of Umi, at which point a young local man sensed that this bet was becoming too violent, and bet his own canoes in favor of Umi, so that his life and bones would no longer be part of the challenge. The local man happened to be a wealthy and important chief, descendent of the rulers of the territories of Hilo and Hamakua. Paiea was only a lowly chief serving King Liloa, and thus his betting capital had reached its limit and he could no longer raise the stakes of the challenge.

With the bet solidified, the young men entered the sea and paddled towards the lineup. Sitting outside the breakers they sat and waited for the perfect wave. Umi rejected the first two waves that Paiea suggested, and then, as a great wave appeared on the horizon, he turned to Paiea and said, “Let us ride this one.”

Paiea firmly agreed and the two surfers stood up almost in unison, demonstrating their great skill and dominance of surfing while quickly advancing along the wave. As they got closer and closer to a reef right in their path, Paiea started to shut Umi out, forcing him in the direction of the reef. To avoid crashing into the coral, Umi turned his surfboard on the inside part of the coral reef, just barely escaping his fatal fate. He then rode his surfboard straight to the beach reaching the shore before Paiea. Victory was his. Koi, his friend and follower, welcomed him with a smile at the beach. When he saw the scratches from the reef on Umi’s shoulder, he leaned in and whispered, “Once you are king of these lands I will kill Paiea.”

Paiea not only lost the competition, but also all of his earthly possessions. This is one of the most frequently told legends passed on by the Hawaiian storytelling tradition. There are many more like it, and thanks to all of these narratives that still exist we can recreate and envision the immense importance of the art of surfing, or he’enalu in the Hawaiian tongue, in this society of great social division.

In January 1778 the English explorer James Cook arrived to the Hawaiian Islands and named them the Sandwich Islands. It is important to understand that during this era both Spanish and Portuguese sailors had already visited the archipelago. In fact, the Spanish had already named them the Islands of Kings in 1543. What James Cook saw from the bow of his ship must have been one of the most astonishing meetings between two divergent different cultures.

“The waves, which break about 20 meters from shore and flows alongside the entire bay, burst with great power. For the natives, the storms and extraordinary waves that whip the coast are the best conditions to challenge the fury of the sea. Between 20 and 30 natives are entering the savage sea with a type of long and slim boards, with rounded point. Not everyone manages to overcome the onslaught of furious waves, and many of them are swallowed by the sea as they try to reach the breaking point. When they do reach it, they lie down on the boards and wait for the next series of waves. Then they choose the biggest one, paddle towards shore, and stand up on their boards to move along the wave with dizzying speed.”

James Cook was the first Englishman to ever witness anything like surfing, so it is not difficult to imagine how impressed he must have been. Here were the Hawaiians, defying the greatest of waves with help only from a fragile piece of wood, their god’s protection and the expertise of men of the sea.

Between 1790 and 1810, the islands were politically united by the leadership of King Kamehameha I, whose five successors, also names Kamehameha, governed the kingdom from the time of his death in 1819 until the end of the dynasty in 1872. At the beginning of 1819, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent eleven groups of missionaries to Hawaii. Led by Hiram Bingham, originally from New England, the Christian missionaries imposed their way of life, morals and culture on all of the islands in the archipelago. With their arrival, surfing declined considerably. The Christians thought the innocent marine pastime to be a pagan rite and ultimately banned. But the Hawaiians had enjoyed surfing for centuries, and thankfully the arrival of a group of foreigners could not stop them from forming secret circles, which on private occasions kept alive the art of surfing.

This religious prejudice, that there was a hidden adoration of pagan gods behind surfing, was strengthened by the disdain the Europeans felt about bathing in the sea. Before discovering the New World, Europe had been laid waste by plague and epidemics. At some point they came to believe that bathing in the sea was the quickest way to contract diseases. The missionaries, who nearly succeeded in eradicating Hawaiian surfing from the face of the earth, were terrified when they saw the natives spend hours in the water—practically naked. For them not only did surfing break serious religious taboos, but it also drastically increased the risk of disease.

As the influence of the European missionaries in Hawaii started to decline in the late 19th Century surfing was reborn. By the turn of the century the islanders had reconnected with the divine gift of the waves, and thanks to the conservation of old boards in sacred places (like the Bishop Museum), the art of surfing started to grow once more. The most important beach to the development of Hawaiian surfing was beyond no doubt Waikiki on the island of Oahu. There the natives brought the tradition back from the brink, and what is even more important, at Waikiki the mixed raced population, children of European-native couples, had their first contact with the sublime experience of riding waves.

One of the first children of a mixed couple to surf in Hawaii was George Freeth, son of an Irish captain and a woman that was the daughter of an English tycoon and a Hawaiian-Polynesian woman. George was born in Honolulu 1883 and started to surf sometime in the 1890s. He was one of the first amongst the new generation of surfers to ride waves standing up instead of lying down, as the majority did in those times. Many natives laughed at him at first, but he soon won their respect for having revived the lost art of standing-up surfing. Freeth is also credited with being the first, or one of the first, to ride the waves sideways, instead of riding the wave straight to shore, which was the custom until approximately 1905.

In the summer of 1907, Freeth traveled from Hawaii to San Francisco, California, bringing with him an eight-foot redwood board. Freeth intended to spread the art of surfing across the American continent, but he practically had to leave the city as soon as he got there as it was still struggling to recover from a devastating earthquake in 1906. With board in tow he left for Los Angeles and Venice Beach.

Freeth was not the first rider to surf on the North American continent. A Hawaiian chief from Kaui had sent three of his sons to study at a military school 20 years earlier in San Mateo (south of San Francisco). In the summer of 1885 the Hawaiian princes visited Santa Cruz (west of San Mateo), and when they saw the wave that formed at the river mouth of the San Lorenzo River, they decided that they needed to build redwood boards and get out there.

Also, a couple of years before Freeth first landed in California the son of the owner of the Aloha Lumber Company in Washington State, built various cedar alaia surfboards, and spent his summer surfing with a group of friends in the cold waters of Joe Creek on the Olympic Peninsula.

When Freeth arrived in Los Angeles he was invited to make a public demonstration of the Hawaiian art of surfing in Redondo Beach, south of Venice Beach, as a part of the opening festivities of the new railway connecting Redondo with Los Angeles. The show put on by Freeth during his legendary demonstration was so impressive and skillful that the prosperous company that ran Redondo Beach hired him as a lifeguard to protect the beach-goers, who finally having left behind centuries of prejudice, were starting to bath in the sea.

While Freeth was not the first surfer in the U.S., thanks to him the sport grew in popularity across the continent. He would surf during his shifts as a lifeguard, admired by women and envied by men. He spent the rest of his life saving others until he succumbed to a fever in San Diego when he was only 35 years old. Before he died, he saved 78 lives and was chosen to represent the United States in swimming in the Olympics. Freeth was, and will always be, considered one of the most important ambassadors of the sport of surfing.

The popularity of surfing quickly grew in North America. Soon there were small bands of surfers were travelling up and down the California coast uncovering the myriad waves that would eventually become household names. It didn’t take long for the Americans to realize that Hawaii was the natural paradise of the aquatic sport. Soon the islands came to embody the perfect vacation spots and Hawaii would undergo a massive wave of change. All of a sudden everyone on the mainland wanted to come discover paradise. To house the new tourists arriving to Hawaii in search of an exhilarating experience hotels were built all along the Waikiki waterfront. Famous hotels like the Moana and the Royal Hawaiian were filled with tourists who would watch the natives surf with the same astonishment as James Cook two centuries earlier. Upon arrival, the tourists were received with leis (flower garlands), the sweet tunes of ukuleles, exotic hula dancing and aphrodisiac filled drinks. They also came in contact with Hawaii’s abundant wilderness, and there was surfing, epitomizing all that was beautiful and romantic about the islands.

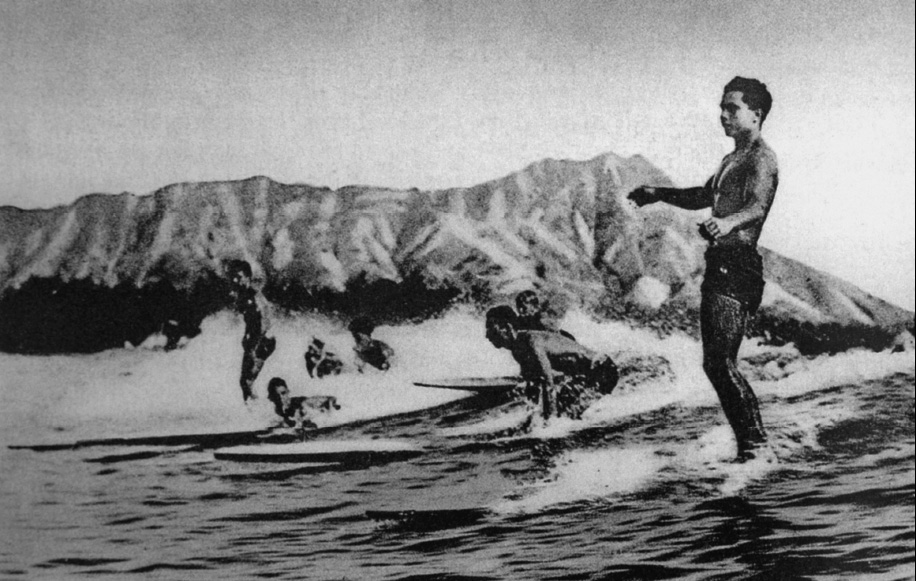

Duke Kahanamoku was born in Honolulu on August 24, 1890. He grew up with his brothers in Waikiki, swimming and surfing waves with elegance and graceful assertiveness. The young lifeguard, foreign and fascinating to the tourists, was an exceptional man and destined to become one of the greatest athletes of all time. When the tourist industry established itself in Waikiki, Duke and his brothers were hired as “beach boys.” They spent more than eight hours a day in the water, tending to tourists and their clumsy needs. Teaching them how to catch a wave—and eventually saving them from drowning—the Kahanamoku brothers became expert swimmers and exceptional surfers. They surfed with their back to the shore, jumped from one board to another while riding, turned left and right depending on how the wave broke, and performed the tandem style, sometimes riding with a dog, or if they were lucky, one of the attractive tourist women.

By the early 20th Century, Duke was already known as one of the best swimmers in the islands, but it was in 1911 when he truly rose to fame. Breaking three Olympic records in freestyle swimming at a swimming competition in Honolulu Bay, the feat turned heads around the world. The year after the young Hawaiian was invited after to compete in the Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden.

Preceded by his reputation as half fish and half man, Duke impressed the world by winning the gold medal in 100 meter freestyle, breaking the world record in the process. He also won the silver medal in 4 x 200 meter relay. These two triumphs established the legend of the Duke—the fastest swimmer and greatest surfer in the world.

Duke returned from the Olympics in Sweden a bonafide celebrity, and had the ambition to keep representing the United States in the next Olympics Games. Since he refused to receive monetary compensation for his swimming demonstrations and shows he was in a bit of tight financial situation, so in the end of 1914, Duke traveled to Australia where he spent three months showing off his skills as a swimmer and teaching surfing to a wide audience. He was received him with great warmth. The Australians even overlooked their “White Australia Policy,” inviting him to all of their swimming events since he was not only the best swimmer in the world, but also a world famous celebrity, an American citizen and had made friends with all of the Australian swimmers at the Olympics in Stockholm. It was all the motivation anybody needed to ignore the fact that he was dark skinned.

Per Duke’s suggestion, they arranged a surf show at Freshwater Beach near Sydney. The waves weren’t great, but Duke managed to put on a spectacular show. This success led to other surfing shows at other beaches around Sydney, attracting bigger and bigger audiences every time. A month later, Duke returned for a second show at Freshwater, which is by far the best documented and remembered of all.

On August 10, 1915, in the crystal clear, temperate water of the beautiful beach Duke teamed up with a 15-year-old Australian girl named Isabel Letham. Together they entertained the audience surfing in tandem. Letham continued to surf until she was 60 years old and is often described as the First Lady of Australian Surfing. When Duke arrived in Australia everyone that lived there was convinced that they didn’t have waves that worked well for the new sport, but by the time Duke’s visit was coming to a close he’d proved otherwise.

In 1918, Duke was back in the United States and set off on a cross-country tour of swimming shows in order to fundraise for World War I. Little by little his fame grew. Eventually the name Duke Kahanamoku became synonymous with the Hawaiian people’s strength and vigor.

In 1920, Duke received the Prince of Wales, who traveled to Hawaii for the sole purpose of getting to know him. Duke took it upon himself to teach the Prince the secrets of surfing, and after an extended stay the young heir of the Welsh crown declared that he had had the most gratifying time of his life. Surfing, the pastime of ancient Hawaiian royalty, was now seducing members of European royalty. From that day on, Duke started to advocate for surfing to become an Olympic sport, conscious of the prominent future ahead.

The Olympic authorities did not pay him much attention though, so at the Antwerp Olympics in 1920, Duke focused on swimming and won two more gold medals, one in 100 meter freestyle and the other in 4 x 200 meter relay. Thirty years old at the time, and was undoubtedly the fastest and most resilient swimmer in the world, Duke was at the top of his game.

In 1929, during a giant swell that unleashed the fury of the Hawaiian sea, Duke accomplished a memorable feat when he caught a grand wave far out at sea and surfed the longest distance ever ridden on a surfboard. In addition to being the fastest swimmer on the planet and a Hawaiian ambassador, Duke thus became the father of all big-wave surfers. In 1932, when Duke was 42 years old, he once again represented the United States in the Los Angeles Olympics, being part of the water polo team, which unfortunately did not make it to the finals. In 1935, Duke was declared a national hero after saving seven fishermen whose boat had capsized as it was entering the Newport Beach Harbor in California. His accomplishments had turned him into a living legend and people from all over the world who came to Hawaii to learn how to surf had the pleasure of knowing him in person. One of these individuals was the Peruvian surfer Carlos Dogny Larco, who learned how to surf with Duke on the Waikiki waves.

In 1965, the first Duke Kahanamoku Invitational Championship was organized at Sunset Beach, Hawaii. This event became an annual competition, where 24 of the best surfers in the world would be chosen to compete. Peruvians Felipe Pomar, Sergio Barreda, Ivo Hanza, Oscar Malpartida and Fernando Ortiz de Zevallos all competed in this championship. The contest ran until 1984.

The great Duke Kahanamoku passed away at the age of 77 on January 22, 1968. His ashes were offered to the sea in an ancient Hawaiian ritual.

CHAPTER ONE: THE FISHERMEN SURFERS

CHAPTER TWO: NAVIGATION IN ANCIENT PERU

CHAPTER THREE: A PLAUSIBLE PERU-POLYNESIA CONNECTION

CHAPTER FOUR: THE HAWAIIAN TRADITION

CHAPTER FIVE: CARLOS DOGNY LARCO AND THE CLUB WAIKIKI (1938 - 1949)

CHAPTER SIX: THE FIRST YEARS WERE INSTITUTIONAL (1950 - 1959)

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE AMAZING DECADE (1960 - 1969)

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE RISE OF THE BROTHERS OF THE SEA (1970 - 1979)

CHAPTER NINE: EVOLVE WITH YOUR SPORT (1980 - 1989)

CHAPTER TEN: THE BEGINNING OF MODERN HISTORY (1990 - 1999)

CHAPTER ELEVEN: PERU: TOP LATIN AMERICAN SURFING POWER (2000 - 2009)