The sport of surfing in Peru gained momentum after Felipe Pomar’s world title and the foundation of the International Surfing Federation (ISF) by Eduardo Arena. Peruvian surfers entered the 1970s with a well-established, worldwide reputation. The era of discovering new beaches that was ushered in during the ‘60s flourished as adventurous surfers from Lima pushed into new territory. Northern Peru enjoyed a classic period of discovery as majestic waves such as Cabo Blanco and Mancora were first ridden.

Globally surfing was in the midst of a boom in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, driven forward by the experimentation and subsequent improvements of surfers like the American Jack O’Neill, who invented the wetsuit, and the Australian Bob McTavish, who dramatically improved the performance characteristics of surfboards. All of this equipment found its way to Peru and the country’s surfers made full use of it.

In Lima the construction of the Via Expresa—a freeway connecting downtown Lima with Barranco—was finished, finally connecting the missing part of the Circuito de Playas de Costa Verde, a highway linking the beaches of Miraflores, Barranco and Chorrillos. With new board designs, new gear to keep them warm, new access to different beaches and the perk to belonging to one of the most powerful surf houses in the world, Peruvian surfers thoroughly enjoyed the 1970s.

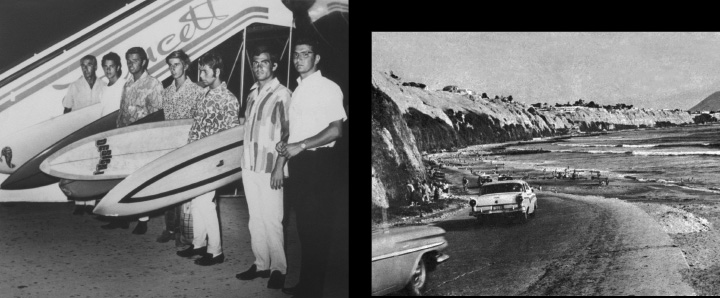

In 1970, Eduardo Arena, still at the helm of the ISF, invited the best surfers in the world to compete in the fourth Surf World Championship in Australia. It was set to run on May 1-14, 1970, at Bells Beach, Victoria. Under stormy skies California’s Rolf Aurness won the men’s division, and Sharron Weber from Hawaii won the women’s. The Peruvian team was selected based on results from a series of International Surfing Contests held at three different Lima beaches: Pasamayo, Punta Rocas and Waikiki-Miraflores. The three-stop tour attracted big names to Peru, including Joey Cabell, Peter Balding, George Downing, Jimmy Blears and Paul Strauch. In the end Joey Cabell barely defeated Gordo Barreda and George Downing in the final.

After the small waves and warm waters of California and Puerto Rico during the second and third ISF World Surfing Championships, in 1966 and 1968 respectively, the best surfers in the world faced a much more different scenario at Bells Beach. With the “Shortboard Revolution” in full swing they were all riding considerably smaller boards in the cold waters of Bells Beach and Johanna in Victoria. The smaller boards were replacing the classic longboards and shapers worldwide were frantically manufacturing the new design to satisfy the demand of surfers who wanted to do more radical maneuvers and push the boundaries.

The semifinals and final heats were held in Johanna and the surf was roaring. The wave’s double overhead barrel became the nemesis of the competitors as they failed to master the powerful break with their experimental boards.

“Surfers went to the extreme, to the point that the winner of the Australia World Surfing Championship was Rolf Aurness, only because he had the bigger board,” recalled Gordo Barreda.

The 18-year-old California surfer rode a board that was 7 feet 2 inches, allowing him to paddle and ride the wave faster and easier than the rest of the competitors.

Peruvian surfers included: Sergio Barreda, three consecutive times national surfing champion 1968, 1969 and 1970, 8th place in the Duke Invitational in 1969, and the runner up in the International Surfing Contest celebrated in Mexico the same year; Oscar Malpartida, two times runner up in the national championships of 1969 and 1970, third place in the Pasamayo International Surfing Event in 1970; Carlos Barreda, second place in the José Duany competition of 1970 and finalist of Pasamayo and Punta Rocas during the International Surfing Event in 1970; Fernando Ortiz de Zevallos, member of the Peruvian Surfing team that participated in the ISF World Surfing Championship in Puerto Rico 1968, recently back from Hawaii where he had been training for the last eight months along with Gordo Barreda” and Chino Malpartida; Augusto Villarán, third place in the José Duany competition of 1970 and third place in the national surfing championship the same year. There were also five other surfers chosen as reserves: Edmundo Arias, Fernando Awapara, Rafael Hanza, Alejandro Rey de Castro and Ivan Sardá.

Once the championship was over, organizers got together to brainstorm about the next venue of the ISF World Surfing Championship, to be held in 1972. It was decided that San Diego, California, would be the place to host this event, thus making the U.S. the host country of the World Surfing Championship yet again.

Peru may have been the first country to experiment with the use of a surfboard leash. Club Waikiki member Fortunato Quesada Lagarrigue, known by his peers as El Técnico (The Technician), became famous among the surfers of the late ‘50s because of a thin rope attached to his board, this way avoiding the well-known hassle of chasing a loose board. Some critics thought him to be crazy, but in reality he was ahead of his time. Years later, in Santa Cruz, California, Pat O’Neill, the son of wetsuit inventor Jack O’Neill, created his own leg rope, an invention that would ultimately change the surfing experience and bring it to the masses.

Before the invention of the leash surfers, although committed and aggressive, typically opted not to take any unnecessary risks for fear of losing their board. This limited their surfing skills due to a lack of experimentation and barrier pushing. There’s no doubt it was a breakthrough in surfing history.

Between 1938, the year that Carlos Dogny brought the first Hawaiian surfboards to Peru, and 1969, surfers faced many challenges. Surfing was a dangerous sport. For instance, if a surfer lost their board in the middle of the ocean, with life-threatening waves crashing around them, he or she would needed to be in an incredible shape to be able to swim hundreds of meters before reaching the shore. Before the advent of the leash it was common to see loose boards being dragged shoreward by the whitewater and a surfer of that time was always on the lookout for lost boards. So, the fact that surfers did not have a leash prevented them from exploring new, more dangerous surf spots such as Punta Rocas and La Herradura; beaches known for their rocks and caves.

New maneuvers were developed thanks to the security of having a leash, but not everybody was happy about it. Veteran surfers complained that now any “kook” could show up at the more dangerous breaks and put other surfers at risk. Before the leash, only experts were riding places like La Herradura and Punta Rocas, guaranteeing a small crowd where everybody knew each other. That scenario changed forever after the leash. Others noted that the drawback of the leash was the loss of responsibility amongst surfers as they were not capable of maintaining control of their boards at all times. None of these complaints stopped surfers from using the device, and very quickly they gained a lot of dexterity due to their ability to practice over and over without wasting their time swimming for their boards.

In 1972, Ricardo Bouroncle travelled to San Diego to participate in the ISF Fifth World Surfing Championship. Representing the Peruvian Surfing Team, there he met Jack O’Neill and talked with him about the possibility of manufacturing O’Neill wetsuits in Peru. When he returned to Peru he partnered with Fernando Ortiz de Zevallos and thinking through O’Neill’s project, they decided to manufacture wetsuits under their own label, which they called BOZ, an acronym for the last name of the partners. BOZ was the first wetsuit company in South America and in the beginning they bought their neoprene fabric from O’Neill. A couple of years into the endeavor Fernando’s brother, Enrique, replaced him as main partner in the company. The company is still in business today.

During this period it was incredibly challenging for the regular surfer to purchase or acquire imported surfing goods, so the main reason behind the BOZ partners’ decision to establish a local business was to make it easier for people to get good, quality wetsuits at affordable prices. Because of a cold-water current, which runs from Chile to Cabo Blanco, BOZ has been an integral company in the development of Peruvian surfing. They’ve been keeping local surfers warm for the last four decades.

The leadership of Eduardo Arena Costa resulted in five successful ISF World Surf Championships. At the same time other successful international surfing events were organized in Peru. José Antonio Schiaffino recalled that Joey Cabell, the winner of the Peruvian International Surfing Contest in 1970, received the hefty prize (in those times) of $1,000 US. Soon, other countries followed Peru’s lead and started to offer monetary compensation to the winners of their surfing events. In 1971, Jeff Hakman won $500US at the first-ever Pipeline Masters. The monetary incentive was highly appreciated by the soon-to-be professional surfers, and surfing, for better or for worse, took another step forward in its development.

Professional surfing events quickly became the preferred stage to showcase the top talent in the word. In October 1976, the International Professional Surfers (IPS) was formed by Hawaiian residents Randy Rarick and Fred Hemmings. A year later the women’s division was created as well. However, after only a few years the criticism of the IPS was widespread and by the end of 1982 Australian Ian Cairns founded the Association of Surfing Professionals (ASP), launching a world surfing circuit in 1983 in an effort to replace the IPS events. The IPS was left with the organization of the Hawaiian surfing contests, while the new ASP was in charge of the rest of the events. The ASP’s popularity grew steadily through the years.

In the early 2010s, professional surfing took another turn when the ASP changed its name to the World Surf League (WSL). This new surfing governing body has included other surfing divisions, including a Big Wave World Tour, but the structure of the organization generally remains the same.

The surfing industry grew alongside the professional events, and soon surfers, like their peers in other sports, started to sign sponsorship deals with the big surfing companies. They all benefited from the increased popularity of the sport. Peru’s contribution to surfing during this period was the flawless organization of several international surfing contests.

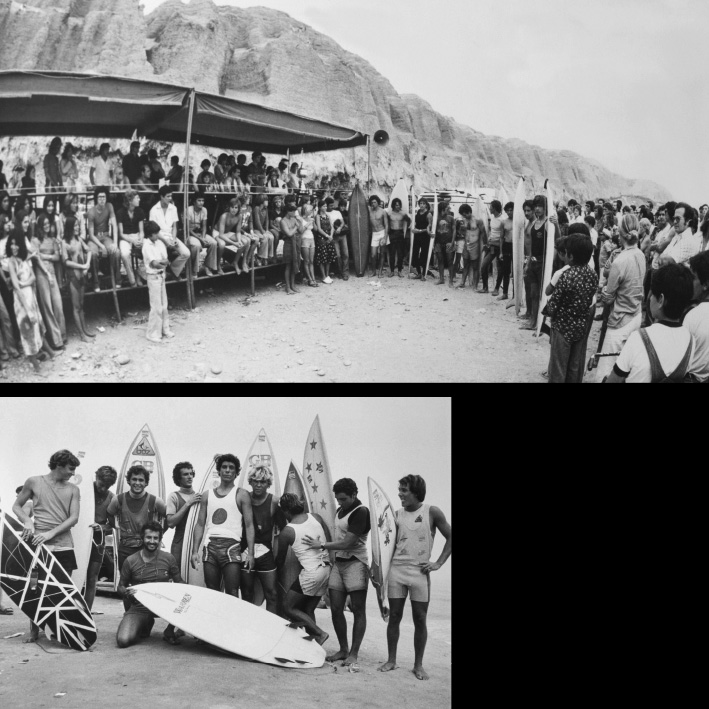

In preparation for the 1972 ISF World Surfing Championship, Peru organized a series of international events to sharpen the skills of their surfers. The first event was in 1971, and once again Punta Rocas served as the venue. Fernando Awapara, a young surfer from Club Waikiki-Miraflores, surprised everybody by beating Carlos Barreda and Oscar Malpartida with ease.

A few months later, on February 7, 1972, during the Southern Hemisphere summer, Carlos Barreda got his revenge by winning the José Duany Championship in La Pampilla-Miraflores. The press reported that El Flaco, Barreda’s nickname, crushed his adversaries and that his skills were loudly cheered and applauded by the audience. The other finalists included: Sergio Barreda (Carlos’ brother), Ricardo Bouroncle, Augusto Villarán and Edmundo Arias. That very month another international competition took place at our beaches. Attended by Stephen Pike and Peter Drouyn from Australia, Harold Holley from California, and Jeff Hakman, John Lindstrom, Brad McCaull, George Downing, Keone Downing (George’s son), and the phenomenal Gerry Lopez from Hawaii.

The presence of Lopez, by then a revered icon in the surfing community, is a good indicator of the quality of the participants at the Peruvian international contests. Gerry Lopez had gained worldwide appreciation thanks to his skillful tube-riding ability at Pipeline, the famous and dangerous Hawaiian surf break located on the North Shore of Oahu.

The name Pipeline was originally coined by Californian Michael Diffenderfer when he was accompanying surf film director Bruce Brown (The Endless Summer) and surfer Phil Edwards. The California gang was travelling along the Kamehameha Highway looking for perfect waves when their dream came true. They spotted a wave offshore at the Ehukai Beach Park. They wasted no time. Edwards went out to ride the wave for the first time in December 1961. While Brown was filming Edwards, Diffenderfer noticed that on the other side of the highway was an ongoing construction project with an uncovered pipeline, and he suggested to Brown that Pipeline was the appropriate name for this newly discovered surf break.

Lopez began surfing the legendary “Banzai” Pipeline in 1963 when he was just 15 years old. During the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s, Lopez was known as the “Master of Pipeline,” his tube-riding finesse and style was beautiful and unparalleled at the time. The Peruvians were grateful to have these wonderful surfers in their events because they understood that by competing against them they would earn respect and an appreciation of their skills. It was not an easy task to earn this kind of recognition from the Hawaiians, the Californians and the Australians, which were the best surfers in the world.

The International Surfing Competition of 1972 was a compilation of several events. One of them was held in La Pampilla, where Lopez stood out. From the very beginning he surfed incredibly and easily won the contest. People were amazed and entertained by his flowing, graceful style. The main event of this International Surfing Championship was the Big Wave Tournament of Punta Rocas, in which Peruvian Gordo Barreda brilliantly defeated Hawaiian Jeff Hakman and Australian Peter Drouyn. Lopez ended up in fourth place.

Seventeen countries attended the fifth ISF World Surfing Championship in San Diego in 1972. Unfortunately the surf remained small throughout the contest and the Peruvian team struggled to make heats. Most of them were big-wave hitters, and given the surf conditions, they failed to how have an impact. The highlight came for the Peruvians when Oscar Malpartida showed his prowess by winning the 2,000-meter paddle race.

In the surf competition only Gordo Barreda was able to reach the semifinal, where he surfed against Hawaiians Jim Blears, Reno Abellira and Keone Downing, as well as Australians Peter Townend and Colin Smith, and Californian David Bolcerzak. The Eduardo Arena Costa Trophy, the prize of the championships since 1965, was awarded to the Hawaiian Jimmy Blears, who received it on the behalf of The Outrigger Canoe Club.

The Peruvian team consisted of Sergio Barreda, Oscar Malpartida, Koki Aramburú, Herbert Mulanovich, Gustavo Reátegui and Ricardo Bouroncle.

In 1964 Hawaiian George Downing came to Peru to coach Peruvians to surf in big waves. For unknown reasons he decided to take ownership of the Eduardo Arena Perpetual World Surfing Trophy, won that year in San Diego by Jim Blears. It is quite possible that the trophy, bearing the names of Felipe Pomar, Nat Young, Fred Hemmings, Rolf Aurness and Jim Blears, is still kept in Downing’s house, who has never explained his actions. The ISA (the current incarnation of the ISF) has requested he return it multiple times, but continues to refuse to this day.

The ISF World Surfing Championship of 1972 had several misfortunes, a lack of budget being one of them. As consequence surfers of the stature of Midget Farrelly, Nat Young and Fred Hemmings did not participate in San Diego. In the women’s division Margot Godfrey was absent as well. Five weeks before the start of the event, the host country organizers announced that they did not have the necessary financial support to carry out the competition and threatened to cancel the event. A crisis arose and angry competitors vandalized a hotel. A car loaned to the organizers by one of the sponsors was also stolen.

Eduardo Arena stood up and confronted the disarray and was able to successfully handle the situation, saving the ISF World Surfing Championship. The San Diego World Surfing Championship was the last one to be organized by the ISF. At the end of 1972 Arena resigned as president of the organization and no one took office after him.

Eventually the International Surfing Association (ISA) was created in its place. Its leader, South African Basil Lomberg, visited Lima in 1977 with the intention of getting to know the country better. Luis Anavitarte Condemarín, the president of the Peruvian Surfing National Committee, rejected Lomberg’s offer due to the rampant racial segregation in South Africa being enforced by the government’s policy of apartheid. In the 1980s the ASP world tour surfers also stood up against the racist oppression. World champions Tom Carroll, Tom Curren and Martin Potter, himself a South African that was forced to move to England, all boycotted major events there.

“Boycotting the South African contests, was simply a basic humanitarian stand,” said Carroll.

In 1978 the ISA organized an event in South Africa. Peru chose not to attend for the same reasons mentioned above. Peru also declined to participate in the ISA World Surfing Contests in 1980 and 1982. It is worth to noting that by the mid-‘70s the IPS was already up and running and they were competing against amateur world surfing contests by aggressively pursuing the best surfers to participate in their events. They marketed them to the big surf companies as the ultimate venue for world-class surfing. The best surfers, media, surfing companies, and eventually the crowd switched their preference from the amateur surfing competitions organized by the ISA to the professional surfing events organized by the IPS.

By the time he was 22 years old Ricardo “Cholo” Bouroncle was already well traveled. He’d landed in Bali and was the first South American to surf G-Land in Java after hearing about the break in Hawaii during the winter of 1969/70. He also happened to be one of the surfers present when Peruvian breaks Caballeros and Playa Grande were discovered.

After surfing G-Land, Bouroncle returned home to Peru, looking forward to the winter waves at Pico Alto. Because the Southern and Northern Hemispheres have opposite seasons the Peruvian winter surf season is particularly good with the big swells coming in from the south.

Bouroncle recalls, “It was in beginning of the winter of 1973 and Felipe Pomar had just arrived to Lima from Hawaii, accompanied by a Greco-American surfer by the name of Dimitri, and we met them in Punta Rocas. I was with Juani Bazo and we were about to go out to surf La Isla (in Punta Hermosa). It was one of those days with mid-size waves, but because it was windy and a little rough we decided to take Felipe and Dimitri to Señoritas (young ladies in Spanish). It is good to know that back then there were no roads, they all ended at Playa Norte (a beach on the north side of Punta Hermosa). We checked the waves from the cliff and we realized that Señoritas was not any better than La Isla; however we also noticed that at the end of the other side of the bay there was a break. We were looking at the break sideways and we couldn’t tell how good the waves were, so we decided to keep walking. That’s when we saw a long and nice shaped right wave and Felipe asked us; What is the name of this wave? We have never ridden that wave before, we answered him. We went out and surfed for three hours, catching several waves far out and riding them all the way to the shore. That was the first time, and it was a very good surf session. We got out of the water, and after getting dressed, Felipe asked us once again for the name of the beach. We told him that that it did not yet have a name, since no one had surfed it before, even though we had surfed the left wave on the other side of the bay (Señoritas) since the year before. He replied. ‘Well boys, because it is next to Señoritas we should call it Caballeros (gentlemen in Spanish), what do you think?’ And we answered, ‘Perfect compadre!’”

Bouroncle continued, “Before starting to use a leash we frequently surfed Puerto Chicama, and every time we headed north to go there we would see this magnificent and huge wave breaking in shallow waters against a volcanic rock slab. We thought of it as a very dangerous wave, and even worse so if you happened to lose your board. During the International Surfing Contest of the summer of 1973, the leash made its entry in the life of Peruvian surfers, and the device encouraged us to surf waves like Peñascal, La Herradura, Punta Rocas more often, and even other surf breaks never ridden before. After the summer the big swells came in and we, as usual, went up north to Chicama. After surfing Chicama we were on our way back to Lima, uncommonly early in the day, and as we were passing by Playa Grande, we saw that the wind had not gained momentum yet, and the waves were beautiful. As such, Mico Tudela and I decided to give it a try. We went out to surf while Flaco Barreda filmed us with a Super 8 camera. The waves were more than what we asked for and Mico got his board broken in three. For the remainder of the trip back to Lima, we did not stop talking about the intensity and force of that wave.”

One of the most important and controversial events of the ‘60s was the construction of the Circuito de Playas (a road linking several Lima beaches). The mayor of Lima at the time was Luis Bedoya Reyes, and he decided that all the earth that was removed during the construction of the Circuito de Playas was to be dumped at the foot of the cliffs from Club Regatas to Bajada de Armendariz. The thought was to claim land from the ocean and eventually have a new, man-made coastline. Tons of construction waste filled the shores of Lima, eventually creating new landmass that came to be called Costa Verde. The multimillion-dollar project was continued by the next mayor of Lima, Eduardo Dibós, who expanded the man-made environment from Bajada de Armendariz to La Pampilla. This “urban improvement” forever changed the coastal makeup of Lima. Before Costa Verde, Lima had five main beach clusters, each with their own beaches, from north to south: Cantolao, Magdalena, Miraflores, Barranco and Chorrillos.

Until the ‘60s the Lima beachgoers accessed their beaches through a variety of methods. For instance, the Waikiki members recalled that to reach La Pampilla they needed to paddle long and dangerous distances to ride the big, long waves that La Pampilla used to offer. Back then treacherous and inaccessible caves dotted La Pampilla shores. The same was true to reach Redondo, and so on and so forth for the rest of beaches.

Before Costa Verde, the southernmost beach of Lima, Chorrillos, had the following beaches: La Herradura, Regatas, Agua Dulce, Ala Moana and Triángulo. The picturesque district of Barranco had Barranquito, Las Conchitas and Los Pavos, and Miraflores enjoyed the waves of Redondo, Makaha, Waikiki and La Pampilla. La Punta in Callao had Cantolao. But the decision to unify all of them by a freeway meant the beaches lost part of their uniqueness and privacy.

Surfers were one of the most affected groups. The waste dumped on the shores was washed away by the waves, modifying the sea floor. In addition, the municipality’s engineers built several jetties to literally stop the waves from hitting the shore. All of these “improvements” changed the shape and length of the waves. Nowadays old-timers remember with nostalgia when Waikiki, right across from the club of the same name, was a famous beach, where surfers were able to ride almost half-a-mile long waves that were well over 10 feet high. Regatas was a fantastic surf break. Credible sources remember it as a double overhead barrel wave like Bermejo. Triángulo was a perfect A-frame wave, and for several years Barranquito was the cradle of several Lima’s greatest surfers.

Today Barranquito almost never has a wave. La Pampilla is a shadow of its former self. We would practically have to wait for a tsunami to show up in order to have the same kind of wave quality that La Pampilla lost during the construction of Costa Verde. It is necessary for the new generations of surfers to know about the history of these waves, so they can understand why surfers like the Barreda brothers and many others spent hours at these beaches, now long gone. The old surfers from the Waikiki club still remember when they had the ocean at their doorstep and all they had to do to surf was to walk a few meters, lay down on their boards and start paddling out with no worries of cars zooming by, threatening their lives.

Life is full of tradeoffs and Costa Verde and Circuito de Playas is one of them. On one side, we have a community of surfers and beachgoers being affected negatively by urban development, and on the other thousands of people benefiting by these development projects. They are now able to reach locations that were inaccessible before, from Chorrillos, to San Miguel, to La Punta, to Callao.

Thanks to the leash and the wetsuit, losing your board and getting cold was no longer an issue for surfers. Consequently, more and more people started to embrace surfing. The demand for new boards kept local shapers busy, and just like surfers all around the world, Peruvian wave-riders were mastering new and more radical maneuvers. Surf competitions were booming and La Herradura was the favorite Lima venue for these wonderful displays of dexterity, commitment and performance. Peruvian surf champion Herbert Fiedler notes that at the very beginning of the ‘70s, when surfers were still riding without a leash, contests in la Herradura only took place when the surf was really big. Therefore, championship organizers, worried about surfers wellbeing and their equipment, instructed the competitors to surf only in the third section of the break to avoid crashing into the rocky caves along the shore.

In 1979 César Aspíllaga (Cabo Blanco tube riding specialist), used to disappear from school for a week at a time, only to later make his entrance back in class tanned and smiling.

“Mr. Aspíllaga, what are the reasons for you to have missed class for the entire week?” the professor would ask.

César simply responded, “I’m so sorry Sir, but the surf was up and La Herradura was pumping the whole week.”

Every time a big swell came in, or as César Aspíllaga would say “the waves were pumping,” Lima’s best surfers dropped whatever they were doing and headed straight to La Herradura. Once there they paddled out, elbow to elbow, towards the point. In the lineup they waited, seated on their boards, for the sets to arrive. The adrenaline coursed through their bodies as the waves started to roll in, exploding against the cliff, giving them notice to get ready for the show.

Riding these waves was both a pleasure and serious commitment. When paddling to catch the waves the surfers would have been immediately sucked in by the wave’s inertia. They needed to rise to their feet immediately to avoid being swallowed by the sea. The next challenge for La Herradura surfers was the abysmal barrel that took form in the first section, a fast, tubing wave. If they survived that they faced the long and big wall of the second section. This wall allowed them to do a variety of maneuvers. Then came the last section, which was an exciting, gigantic, steep wall that created a huge barrel, which could completely cover the surfers and make them disappear from the view of the spectators. As the grand finale, the surfers were spat out of the tube in a bloom of spray, finishing the ride on a high note.

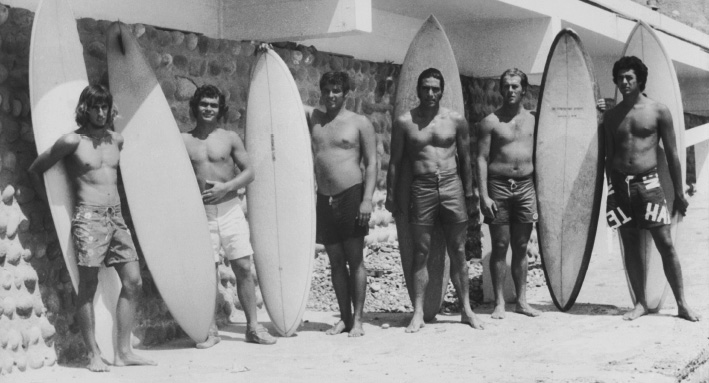

The hardcore La Herradura crew of the 1970s included: “Guayo” and “Tato” Gubbins, Herbert Fiedler, Oscar “Chino” Malpartida, Raúl “Patero” Calle, Raúl Henrici, Erick Sardá, Raúl “Wantan” Risso, Dennis Gonzales, Carlos and José Mujica, Richard Malachowski, Alan Sitt, “Negro” Cordero, Claudio Reyes, “Cholo” Bouroncle, Víctor “La Papa” Fernandini, Enrique Ortiz de Zevallos, “Juan Sin Miedo”, “Niko” Wilhelmi, Ricardo Kaufman, Luis “Chato” Rojas, Edwin Euler, Alex Succar and his brothers, Bruno Justo, Pierre Rodrigo, César “Chato” Aspíllaga, and Mario Chocano.

The national surfing champions of the 1970s includes Sergio “Gordo” Barreda, Fernando Awapara, Oscar Malpartida, Fernando Ortiz de Zevallos, Juan José Miró Quesada, Salvador “Tato” Gubbins and his longtime friend Herbert Fiedler. Tato Gubbins won three national titles. Overall, their self-discipline, their love and passion for surfing and their absolute confidence and determination allowed them to go out and surf any break in any condition. This exemplary surfing lifestyle was followed by other surfers who themselves also gained fame and respect, such as “Geneke” Rey de Castro, Herbert Mulanovich, Miguel “Mico” Tudela, Alfonso “Fonchi” Pardo, the unforgettable Ricardo “Cholo” Bouroncle, Víctor “La Papa” Fernandini and Raúl “Patero” Calle, the latter a true surfing god of the ‘70s.

In November 1979, a travel piece appeared in the America’s Surfing Magazine. Written and photographed by Tony Arruza, in one of the best photos of the article Jaime “Chibolo” Bryce was caught dropping into a huge wave at Pico Alto. Another image shows Raúl Henrici at Punta Rocas. Besides describing Peru’s powerful waves, Arruza also wrote about a tournament held in Punta Rocas between young Peruvian surfers and a team of 14 boys and girls from the USA National Scholastic Surfing Association (NSSA).

During the ‘70s the Peruvian government restricted the import of certain goods, among them surfing equipment. All of a sudden Peruvian surfers had to make their own boards (most of them were coming from California or Hawaii at this point), and overnight the industry blossomed. Blanks, fiberglass, and finally the boards themselves call came to be made entirely in Peru. Surfboard shapers and glassers quickly grew in skill and were able to meet the exceptional demand. There were several foam makers; Gonzalo and Jaime Rosselló were manufacturing Peru Polyurethane Foam, Gustavo Reátegui Rosselló was producing foam called Roger Foam, while Reátegui was making surfboards with his brother Marcelo by the brand Magus, short for Marcelo and Gustavo. However, the most important foam manufacturer was Clark Foam Peru. Carlos Mujica reports that annually Clark Foam Peru manufactured 4,000 blanks in seven different sizes. Mujica once bought 1,400 blanks from Clark Foam Peru to make his Mujica Surfboards, to compete with the other Peruvian surfboards makers such as: La Villa, Magus, Guayo and Tato Gubbins, Herbert Fiedler, Wayo Whilar, Bruja Surfboards, and Gordo Barreda surfboards. The easy access to board materials helped to boost the proliferation of garage shapers, creating a new breed of surfers.

As noted earlier, starting in 1972, entrepreneurs Ricardo Bouroncle and Fernando Ortiz de Zevallos were responsible for the BOZ wetsuit invasion at the Peruvian beaches. Helping the surfers endure the cold winter season, their contribution to Peruvian surfing has been huge.

The year of 1973 should be marked in the Peruvian surfing calendar as the year of the arrival of the Brazilians. Brought here by the dream of surfing the long and perfect Peruvian waves, legendary names like the Maraca, Mudinho, Fedoca and Rico de Sousa came to Peru to enjoy the waves. Although Brazilian surfers first visited Peru in 1969, the travel fever erupted in 1973. All of a sudden it seemed like every Brazilian surfer wanted to surf Peru. The surfing sport was still catching up in Brazil and only a handful of their surfers could compare in skill with the Peruvian surfers, but they eagerly embraced the sport. Inexperienced Brazilian surfers poured into Peruvian surf spots, learning quickly from legends such as Gordo Barreda, Tato Gubbins and Patero Calle.

The Brazilians were not shy in their excitement over surfing. Their loud Portuguese screaming echoed all over Peru’s beaches. The west coast of South America offered them an array of waves ranging from good to great and they made sure to surf all of them. The friendship between the Peruvian and Brazilian surfers was sealed from the very beginning as they continue to visit frequently. Today Brazil is a world surf power, thanks in part to the connection with Peru during the ‘70s.

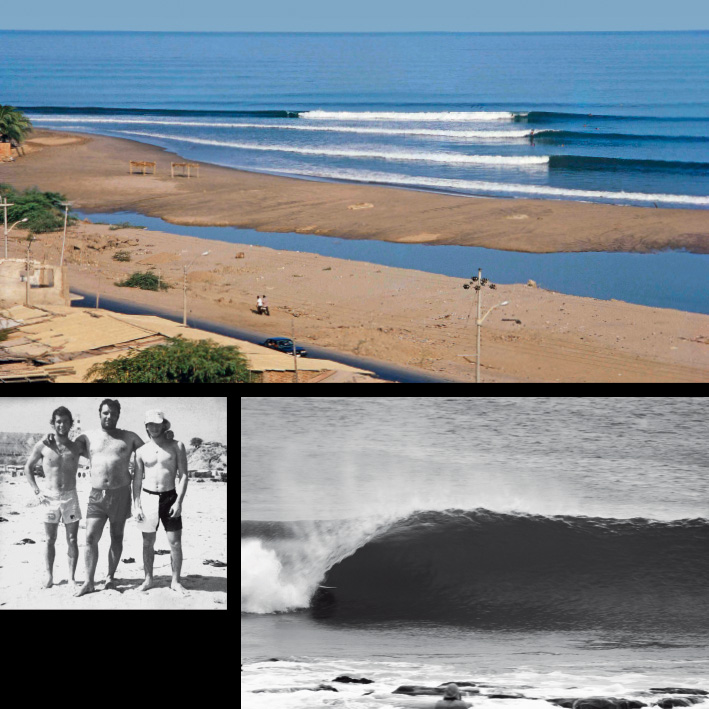

Carlos “Flaco” Barreda and a group of friends were the lucky ones to spot the Mancora break from the highway for the first time (even though some people say that Federico “Pitty” Block spotted Mancora breaking in 1958 while participating in a car race). Without thinking twice, the group went to the cove to watch the wave up closer. They quickly decided to give it a shot. They had no idea that the discovery of Mancora would usher in one of the most appreciated national surfing districts in Peru. Years later it was speculated that an earlier expedition made it to Mancora before Barreda and his friends. Led by Teddy Harmsen, the crew included Juan José “Jota” Miro Quesada, Belico Suárez, Miguel “Mico” Tudela, Herbert Mulanovich, Cuté Ganoza, Dennis Gonzales and Chicho Gonzales.

Regardless who was first, what is important is that these early surfing sessions put Mancora on the map. This idyllic beach community in the Piura region has it all; warm waters, tropical weather, excellent seafood and friendly, barreling waves. It did not take a lot of time for surfers to learn about this beach and soon the phrase “let’s go to Mancora” was being uttered by best of the Lima surfers, who instantly would go home to get their surf gear and head to Northern Peru. It was quite a journey, and it could take as long as 24 hours, but it was always worth it.

Sergio “Gordo” Barreda, one of the surfers who traveled to Northern Peru every time a big swell was announced, explained how he discovered Cabo Blanco. In one of his many trips to Mancora, Gordo and his wife Eva got lost in a road maze built by an oil company. Looking to go back to the main road, they ended up in a fishermen’s cove, called Cabo Blanco. There the couple was blown away by the presence of one the most beautiful waves in the world. These waves were something that Gordo had never seen in Peru. The discovery took him by surprise. He stood up before the reef to contemplate these wonders for several minutes. Fast waves with long barrels were breaking before his eyes and he could not get enough of it. For several years Gordo kept his discovery a secret, visiting Cabo Blanco every time he could, keeping this magical place for himself and a handful of friends.

When Luis Cordero Larrabure, one of La Herradura best surfers, got a job offer from a company located in Northern Peru, he went on his merry way to live in Mancora. He settled in a nearby oil town, “Los Organos.” He was a true waterman and loved to practice any sport associated with the ocean, especially surfing and spearfishing. It was well known amongst freedivers and scuba divers that Los Organos had a large number of reefs and rock slabs—a natural habitat for groupers, parrotfishes, lobsters, octopus, and many others sea creatures. The five Mimbela brothers, who were local spearfishermen, gave Cordero a warm welcoming and Angel, the oldest of the family, taught Cordero the secrets of the area’s spearfishing.

Soon they were exploring Los Organos reefs looking for groupers and parrotfishes. Angel and his brother, Esteban, told Cordero that above the slab of Los Organos, one of their favorite places for spearfishing, they had spotted a very nice barrel wave. When Cordero first heard about the wave he did not quite believe his friends’ discovery. However, on a sunny day in November 1979, Cordero and the Mimbelas were looking for groupers in the slab and had brought a small raft with them as they often did. After a while of freediving Cordero wanted to rest for a bit, and pulled himself onto the raft. As he took off his diving mask he saw it. There it was, the perfect left wave that the Mimbela brothers had been talking about.

The next day at the crack of dawn, Cordero pulled out his 7’2” single-fin shaped by Dick Brewer and drove his pickup truck to the cliff of Los Organos. The wave was still breaking on the reef. Cordero rushed down toward the beach and the magic begun.

Cordero has explained that he was the only one to surf this gorgeous wave for a whole year before finally telling his surfer friends; Chino Malpartida, Herbert Mulanovich, Cholo Bouroncle, Perico Arévalo, Tato Gubbins, Chibolo Bryce and Teddy Harmsen. Basically half of La Herradura’s usual lineup was transported to Los Organos thanks to Luis “Negro” Cordero. Harmsen had a house in Mancora, and he was known by the Lima surfers as “The King of the Gorge.” Harmsen was a great host and Lima surfers were welcomed to stay in his home located in a gorge in Mancora.

Starting in 1976 the national surfing competitions experienced a healthy resurgence. Back in the old days, Peruvian national contests had only one competition that was held at Kon Tiki, which was later replaced by Punta Rocas. In 1976, the National Surfing Commission (CONTA) decided to organize a series of events at a number of different beaches. The idea was to have a versatile national surfing champion, capable of surfing waves of all sizes and conditions.

Beaches like Peñascal, Señoritas, Santa Rosa, Chicama and La Herradura were soon part of the national surfing circuit. Tato Gubbins was the first surfer to win the national title with this new format in 1976. He won again in 1978 and 1979. Gubbins’ friend, Herbert Fiedler, won the 1977 national title. These two surfers were the masters of La Herradura surf break in Lima, yet that they were able to demonstrate their skills in very different waves fulfilled CONTA officers’ initial purpose for change; to crown a versatile surf champion.

CONTA’s initiative was continued by the present-day National Surfing Federation. Other beaches like Cerro Azul, Huanchaco and Lobitos are now part of the circuit.

CHAPTER ONE: THE FISHERMEN SURFERS

CHAPTER TWO: NAVIGATION IN ANCIENT PERU

CHAPTER THREE: A PLAUSIBLE PERU-POLYNESIA CONNECTION

CHAPTER FOUR: THE HAWAIIAN TRADITION

CHAPTER FIVE: CARLOS DOGNY LARCO AND THE CLUB WAIKIKI (1938 - 1949)

CHAPTER SIX: THE FIRST YEARS WERE INSTITUTIONAL (1950 - 1959)

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE AMAZING DECADE (1960 - 1969)

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE RISE OF THE BROTHERS OF THE SEA (1970 - 1979)

CHAPTER NINE: EVOLVE WITH YOUR SPORT (1980 - 1989)

CHAPTER TEN: THE BEGINNING OF MODERN HISTORY (1990 - 1999)

CHAPTER ELEVEN: PERU: TOP LATIN AMERICAN SURFING POWER (2000 - 2009)