It is impossible to talk about the evolution of Peruvian surfing without talking about Carlos Enrique Dogny Larco (1909 - 1997). A celebrated athlete, he was the son of French cavalry officer Eduardo Dogny Marmiesse, who came to Peru as part of a delegation that was assigned to organize the Peruvian Army, which had been left in pieces after the war with Chile. Eduardo Dogny married Ms. María Larco Herrera, who eventually gave birth to Carlos Enrique Dogny Larco. Born on July 25, 1909 in the bayside neighborhood of Barranco, on his father’s side he inherited a fierce temper and an iron will. On his mother’s side he inherited the grace of one of the most famous families in Peru.

Carlos Dogny spent his childhood in Barranco before attending high school in France and England. After graduation he went to college in the United States, where he worked on a degree in agricultural engineering with a doctorate in economics. With his degree in hand he set out travelling around the world. A keen sportsman, at one time or another he enjoyed participating in just about every sport known to man. He rubbed elbows with royalty and international jet setters, including the beautiful French actress Brigitte Bardot, Queen Margaret of Denmark, and the famous “princess with sad eyes,” Princess Soraya. His cosmopolitan life shaped him to become a composed and sophisticated man.

“My philosophy in life is of mental and physical balance, and to lead a useful life. I do not agree with the general life of businessmen, or the simple mortal man, who live their life from one extreme to another, forgetting the importance of balance,” said Dogny in an interview with the Peruvian press in the 1960s. “I spend six months of the year in Lima and six months travelling. While I love the east, Paris is where the action happens.”

In 1936, and Carlos Dogny Larco found himself working in his uncle’s office in New York. His uncle, Rafael Larco Herrera, worked in the mining industry and had summoned Carlos to join him at the office due to his business acumen. His performance in sales, and the export and import of minerals and metals between Lima and New York was excellent.

One day while still working for his Uncle in New York the French Polo team came to town. Passing through on their way to Hawaii, they invited him to join them and play on the team. Being the son of a French cavalry officer, Dogny was an excellent horseback rider and his polo skills were known worldwide (polo had already been included in the Olympics.) Sporting the colors of France, he arrived for the very first time to the exotic islands of Hawaii. After the rigorous competition he went back to the hotel on Waikiki beach where the French team was staying. He gazed out from his balcony and was stunned by what he saw: a group of islanders surfing the waves on great wooden boards.

It is easy to imagine what might have gone through Dogny’s head at the moment he first saw what would become the driving passion of his life. He would have been overcome with emotion. After practicing innumerable sports throughout his life, Dogny felt he had stumbled on something completely groundbreaking, an activity that combined everything he was looking for: novelty, excitement, connection to nature and a great dose of danger. Filled with enthusiasm, Dogny was determined to find out who these men were and what they were doing.

He soon found out that the men were “beach boys,” a group of Hawaiian locals and experts in all things related to the sea. They worked as lifeguards at the luxurious beachfront hotels. When they had time off, they would take every opportunity to practice the ancestral sport of Hawaiian royalty. When Dogny enquired how he could learn to surf like them he was told to go down to the beach as they were coming into shore. From the beach he could watch their maneuvers, performed with majestic elegance. With all of the gumption of a 25-year-old, he swore to himself that he would do everything in his power to learn to surf like them.

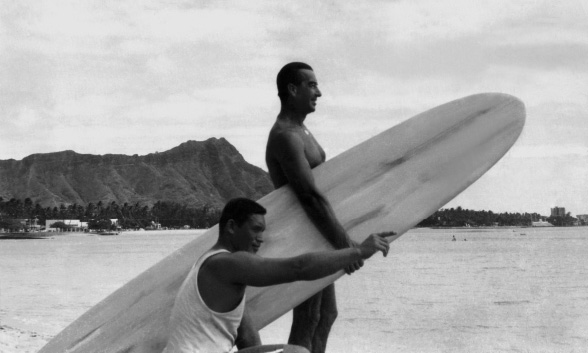

Dogny anxiously waited on the sand for the beach boys to come in. He could hardly contain himself and his desire to master the marvelous art of surfing. As he sat and watched one of the surfers caught a great wave and rode across the water with unmatched grace and control. He rode the wave all the way passed Dogny. The Hawaiian surfer was immense with a broad chest and deep tan from years spent under the sun. Dogny stepped forward and offered his hand and the native did the same. It was none other than Duke Kahanamoku, who immediately recognized Dogny’s enthusiasm and knew that this athletic young man had been touched by the spiritual beauty of the sport of kings. Generous as always, Kahanamoku offered to give Dogny his first surf lesson.

The next morning they entered the foamy waters of Waikiki beach and Dogny begun to learn the basics of this exciting new sport. Kahanamoku realized early on that Dogny, with a bit of effort, had what it took to learn how to surf well and agreed to sell him his board—shaped by another surfing pioneer named Tom Blake. A couple of days later Duke had to leave Hawaii for business reasons, however before he left he made sure to find a suitable replacement to continue his work with his Peruvian disciple. Thus, Dogny was introduced to his second teacher, the unforgettable Albert “Rabbit” Kekai.

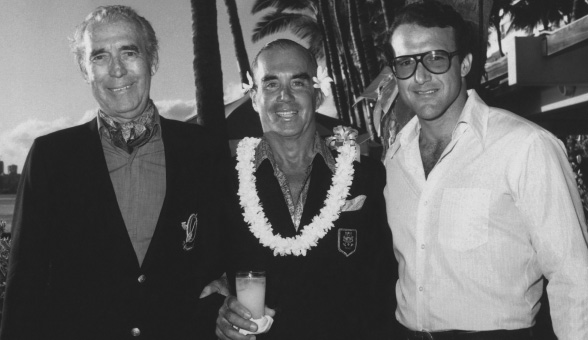

Duke Kahanamoku and Carlos Dogny parted ways as good friends, each heading in their own direction. Once back in New York, Dogny immersed himself in work but could not shake the idea of returning to Hawaii to keep surfing. A year later his wish came true. Dogny was set to return to Peru and decided to bring his new sport with him. He shipped his surfboard—which was over 13 feet long and weighed more than 110 pounds—on the Japanese ship Umaru and prepared to make history.

Carlos Dogny Larco started to surf the Peruvian waves with his Hawaiian board in the summer of 1938. His acquaintances testify that he would travel to every beach possible, from Tumbes in the north to Mollendo in the south, in search of just the right waves for the new sport. He even travelled to other countries in South America, but as surfing sometimes is, he ended up finding great waves just a couple of blocks from his house in Miraflores.

Walking along the boardwalk, Dogny could watched endless line of waves wash in towards Miraflores as if they had been waiting for him for centuries. Miraflores appeared to have the perfect combination of conditions that made surfing possible: good swells and water warm. Shortly thereafter Dogny had his first surfing session in Peruvian water.

Unaware he was bringing back a 5,000-year old tradition in his country, in an interview with the daily paper La Crónica on Sunday, December 16, 1962, he confessed, “Tired of wandering around the world looking for new thrills in sports, I found myself on the enchanted island of Hawaii, where the practice of surfing is patriotic, and even more so, aristocratic. For ages, the skill of surfing has been used as the deciding factor when kings chose their generals. It fascinated me, and I learned to master it, and wherever I would go I tried to find the right conditions to practice it. Never would I have thought that Miraflores was the ideal place to practice this passionate sport, who in present day has had many surfers visits its beach, and more joining every day.”

When he was first seen taking off on the waves of Miraflores he caught the summer guests by surprise. The people watching from the boardwalk could not make out who the athletic figure was that rode the waves in harmonic balance on his board. The sight was so extraordinary that many proclaimed that it was “the devil in human flesh,” a “man from another planet,” or even a “Japanese spy.” One thing was certain, the presence of a man riding waves didn’t go unnoticed. The reactions created two camps: The ones who were frightened by the “man who walks on water” and the ones who wanted to do the exact same thing themselves.

Thanks to Dogny, beloved individuals like César Barrios and Enrique Prado, along with a handful of others, decided that they too wanted to learn to surf. One of them, the unforgettable Carlos Origgi, explained afternoon at the Terrazas Country Club that when he saw Dogny majestically surfing the waves, he could not fight the urge to throw himself into the water and swim until he caught up with him far from shore. Just like his teacher Duke Kahanamoku had done before him, Dogny offered to teach Origgi how to master the sport of kings.

The author and founder of the Kon Tiki Surfboard Museum, José Antonio Schiaffino, researched the original Barranco surfers and discovered that before the first Hawaiian surfboard was imported to Peru by Carlos Dogny Larco a group of swimming enthusiasts were the forerunners of standup surfing in Peru.

Jorge Odriozola Barbe (1895-1981) was a skilled swimmer, rower and member of the Lima Regatas Club. In 1920 he asked Toribio Nitta Kisme, a Japanese immigrant and carpenter who assisted in the construction of the local baths in the neighborhood, to make him a board. The design was not made according to any exterior model, nor was it inspired by the ancient caballitos de totora (although it also had a curved front pointing towards the sky). The board, made from cedar, was two meters long and seventy-five centimeters wide, and surprisingly, worked well on the waves of Barranco Bay.

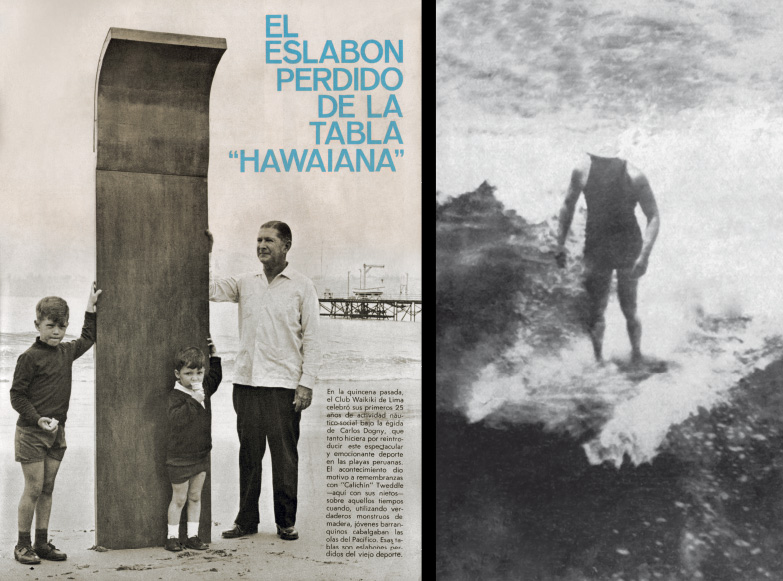

Odriozola’s friend, Armando Fabbri Verese, also enjoyed this hobby and soon many new names appeared alongside them, including Gustavo Berckemeyer Pazos, Luis García-Corrochano Santillán, Alfredo Granda Pezet, Guillermo Martínez de Pinillos Castro, Alicia Otero, Carlos Tweddle Valdeavellano, “Gordo” Bellido Berghusen, and the brothers Ricardo, Jorge and Ernesto Pazos Varela. Initially the hobby was banned from time to time due to the risk of hurting other beach-goers, but the prankster “surfers” would always return a couple of days later to ride the waves and enjoy themselves.

By 1930 there were allegedly ten surfers in Barranco. Although small in number, they early Peruvian surfers are worth noting. Considered a parenthesis in the country’s wave-riding history, with no international or national surfing influences beyond Barranco, Schiaffino managed to prove with his research that the first Peruvian surfers in the 20th century came from Barranco, predating the Hawaiian influence ushered in by Dogny.

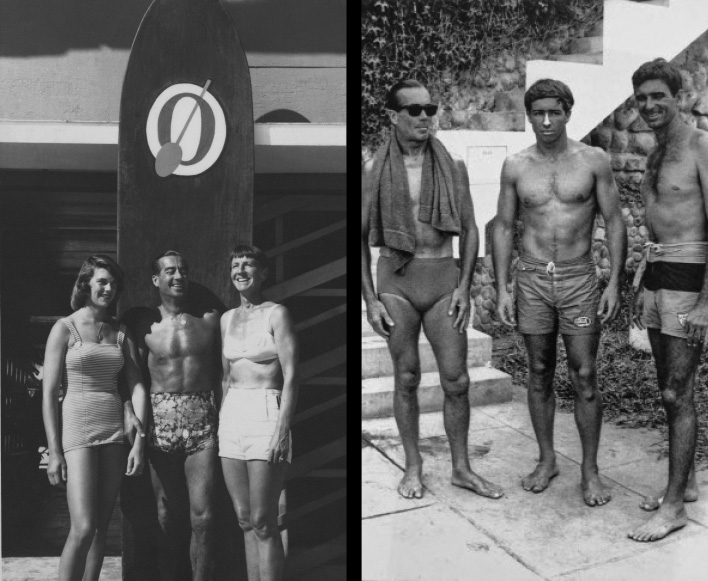

Dogny kept surfing in Miraflores and before long he was not the only surfer in the bay. The problem they faced in the early days was that in all of Peru there was only one surfboard—the one Dogny brought with him from Hawaii. While the group of surfers was slowly but steadily growing, Dogny’s board (which can be seen in a place of honor in Club Waikiki today) was unwieldy to say the least. It was 13' 7" long and weighed between 130 and 175 pounds, depending on how much water had soaked into it. The board featured a bronze plug to empty the water out and a handle to grab in case of emergency.

Carlos Origgi, César Barrios and Enrique Prado, all critical individuals in the development of Peruvian surfing, were personal friends of Dogny. They were soon invited to try out the “new” sport in the waves of Miraflores and would join him at the beach if the conditions were favorable. They would take turns catching waves and riding in to shore. Since they needed more boards to practice as a group, Dogny, Origgi, Prado and Alfredo Álvarez Calderón decided to turn to the carpenter of the Boat Club in Lima for help. They asked him to build a replica of the only board they had. The doors of Luciano Montero’s workshops opened for what would be the first surfboard made in Peru.

Using mahogany, Montero ended up building an authentic copy of the original. Dogny and his companions immediately carried the new board down to the beach to try it. Unfortunately the results were far from satisfying. With the swell up, neither Dogny’s board nor Luciano Montero’s mahogany board withstood the impact of the rocks. Both boards suffered extensive damage and would need extensive repair. With their spirits undiminished, the would-be surfers approached another carpenter, Alejandro Montero, Luciano’s son. He shaped several different models, some more successful than others. It was relatively hit and miss until Hugo Parks reached out to Gerhardt Schreier, a German man, who managed to shape the first efficient surfboards in his workshop in Callao.

During the research for this book it was discovered that Enrique Prado in fact ordered the first Peruvian surfboard. It was to be made by the timber company Ciurlizza Maurer. Thanks to the invaluable help of Carlos Rey y Lama, we found the corresponding receipt of the board dated February 22, 1941. Called a “wave rider,” it was made out of quarter-board and mahogany, held together with bronze screws. It cost 199.95 Peruvian soles. To many people the board is considered the first surfboard made in Peru, but if we take into consideration the first couple of boards shaped by Luciano and his son Alejandro, as well as the testimony of Hugo Parks and consistent references from club members of the time of the “Molnya” board shaped by the German woodworker Schreier, this assumption appears to be incorrect.

Based on what we have learned from Hugo Parks, Gerhardt Steiner was in charge of building and repairing the boats in Callao and this experience was paramount in deciding to ask him to build a surfboard. Parks already knew Schreier, who would periodically repair his sailboat, the Odyssey (with which he became a sailing champion from 1940 to 1943). At the time Schreier was considered the best naval carpenter in Callao, which by default meant the best in Peru. In 1946, Schreier built his first board from Oregon pine and marine quarter-board, which withstood the encounters with the rocky shore thanks to its great flexibility. The board was an instant success and Parks named it Molnya, in honor of Marshall Rokhossovski, a war hero from Stalingrad whose name meant “Lightning.”

After testing it the young surfers reached the conclusion that the board was working to perfection. For its final test Carlos Dogny himself invited two showgirls from Urca, the most famous cabaret in Copacabana, to put on a tandem demonstration in Miraflores. Both ladies were 6’ 2" tall, but the three of them managed to surf two or three small waves together to the delight of the beachgoers and a cameraman for a local newspaper who broadcast his recordings in movie theaters.

The success of the “Molnya” surfboards was such that the young men of Miraflores flooded Schreier with orders. Soon Dogny, Origgi, Barrios, Prado and Prado all had similar boards to Hugo Parks, and thus the first Peruvian surfboard was born.

The “Molnya” board undeniably had many advantages compared to the first board that Dogny brought over. Only weighing 73 pounds and not absorbing any water, immediately it was a success. Hugo Parks said, “All of the boys congratulated me on having found such a precise solution to the serious issues of weight and leakage of the chorrillana boards (a board made in Chorrillos), who needed constant draining. My board was only drained one single time during its first year of use, keeping its weight of 73 pounds by the end of the year.” What is even more important is that now the view of the “man walking on water” had progressed. It was no longer only Carlos Dogny Larco who enjoyed surfing the playful waves of Miraflores, but rather a group of friends sharing the same passion.

To borrow from the old naval cliché, once people in Peru started surfing it was relatively smooth sailing. In the beginning of 1940 there was only a small group of ten surfers around Miraflores. Their memories of the “good old days” are peppered with uncrowded lineups and wide-open beaches. They took to the water before any of the long jetties or groins had been built. The waters of Miraflores were wild and uncontained. Waves broke more than 1,600 feet offshore, sometimes topping eight to ten feet. And of course the surfers of this era didn’t use any kind of leash. It hadn’t been invented yet, and besides, given how heavy their boards were a leash would have practically ripped their legs off. Without the convenience of a leash every time a surfer fell his board was inevitably taken to shore with great speed, leaving the surfer at the mercy of the ocean. This was probably the reason why all of the first surfers, without exception, were excellent swimmers, capable of swimming great distances.

All was idyllic up until 1940 when a massive earthquake struck Peru. The facilities of the Miraflores Public Bath were extensively damaged and the young surfers found themselves in need of a place to rinse off and change clothes. For starters they rented the three outermost rooms of the municipality of Miraflores, cleaning and preparing them for the needs of the club that was forming. From the early ’40s, Dogny and his friends had gained the permission of the municipality to store their surfboards in a small storage room in the Miraflores baths. To bring the surfboards from the city to the beach and back every day would have been way too much effort for the surfers, and thanks to the support they received from the municipality of Miraflores, the pioneers were able to make life a little easier for themselves.

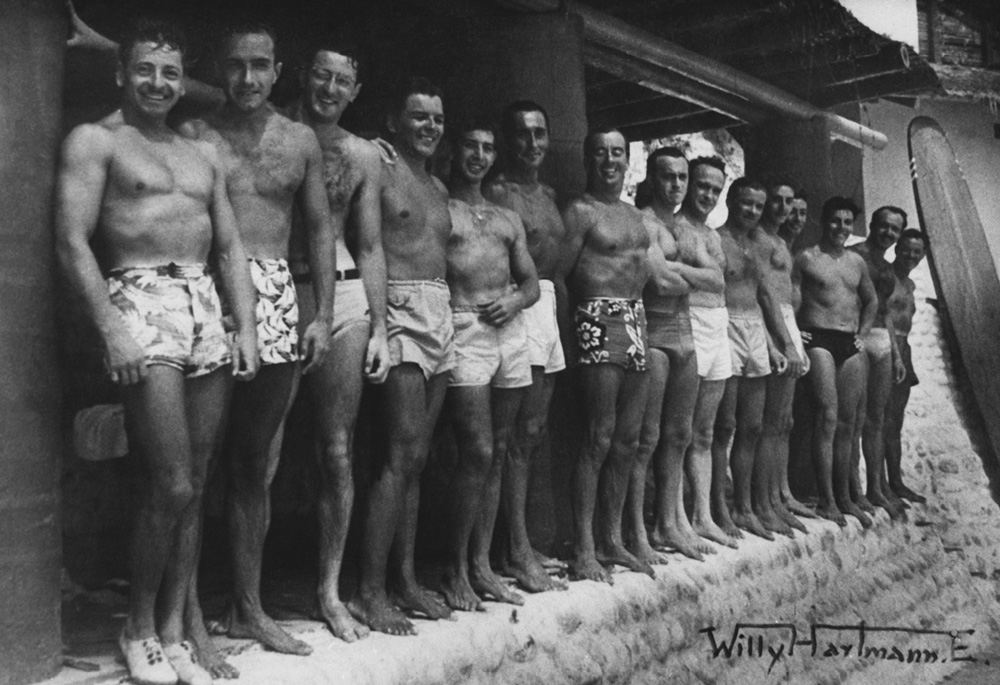

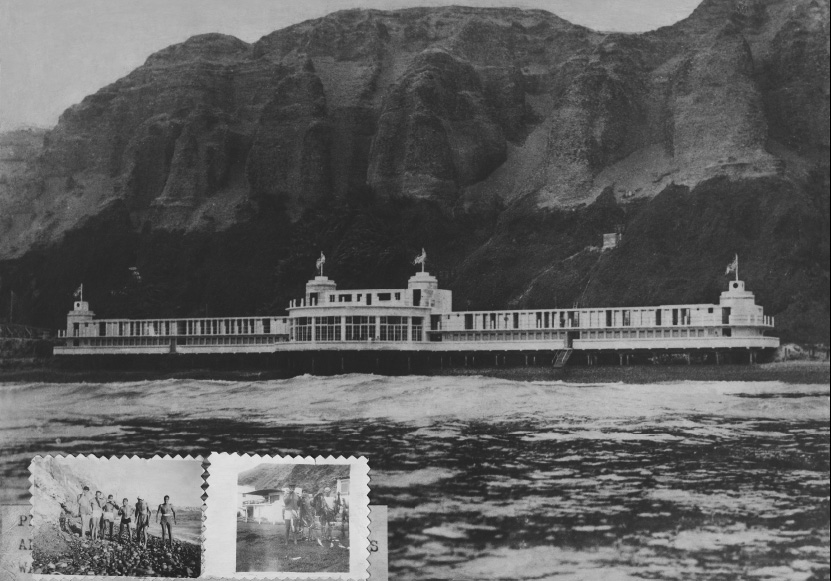

As time passed, on this very piece of land this early group of surfers built the Waikiki Club. Under the leadership of Carlos Dogny Larco, who by then had become the sports councilor of the Miraflores municipality, the club began to take shape. He was assisted by César Barrios Canevaro, Carlos Origgi Camagli, Enrique Prado Heudebert, Hugo Parks Gallagher, the brothers Alberto and Alfredo Álvarez Calderón Wells, Alfonso Pardo Vargas, and Jorge Helguero Aramburú. With the support of the ruling Mayor of Miraflores, Carlos Alzamora, the pioneers obtained permission to build a small clubhouse in front of the waves of Miraflores. With the founding of the Waikiki Club the surfers now had a place to meet and socialize before and after enjoying Miraflores’ bountiful waves.

Little by little the beaches around the Waikiki Club were baptized with names connected to the sport. Makaha and Redondo Beach were named after two famous surf points in Hawaii and California, respectively. The oldest members of the club hold fond memories of the first days of their beloved club. In those times there was no road along the shore connecting the different beaches and the waves rolled all the way up to the club’s front yard. With a few steps they were in the sea and riding waves. The club, while modest, was a true paradise for these first modern Peruvian surfers.

The clubhouse officially opened on December 7, 1942, which is largely considered the official birthday of Peruvian surfing. The handful of men that laid the foundation for the Waikiki Club carries the honor of being the first Peruvians to surf the long and generous waves of Miraflores on Hawaiian-style boards. It was them that led the way for new followers to pickup and enjoy the sport. Obviously the performance aspect of surfing has progressed dramatically in in the 80-plus years since, but thanks to archival photographs their impeccable style and majesty in the Peruvian surf speaks volumes about their enthusiasm.

In those early years of Peruvian surfing, when one visited Miraflores beach they would stop in their tracks as they saw the dizzying movements and bravado of these early wave-riders. For example, Carlos Dogny Larco sported a patented surf style that stood out from his companions. He sometimes surfed standing on his head. Or sometimes he would ride in tandem, balancing beautiful women on top of his shoulders. It was beyond all doubt that the Waikiki Club members were having the time of their lives.

It is interesting to note that the characteristics of the waters off of Miraflores in the ‘40s was completely different than today. For starters, there was no road along the shore connecting the different beaches. Neither were there any jetties, whose eventual construction would change the waves’ characteristics. The waves used to break further away from the shore (1,600 feet to be exact) and were bigger (with a big swell the waves could be as high as ten feet). They are now a shadow of what they used to be. It’s difficult to grasp how exciting the sessions must have been for the first surfers in Miraflores without considering these changes in the coast.

CHAPTER ONE: THE FISHERMEN SURFERS

CHAPTER TWO: NAVIGATION IN ANCIENT PERU

CHAPTER THREE: A PLAUSIBLE PERU-POLYNESIA CONNECTION

CHAPTER FOUR: THE HAWAIIAN TRADITION

CHAPTER FIVE: CARLOS DOGNY LARCO AND THE CLUB WAIKIKI (1938 - 1949)

CHAPTER SIX: THE FIRST YEARS WERE INSTITUTIONAL (1950 - 1959)

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE AMAZING DECADE (1960 - 1969)

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE RISE OF THE BROTHERS OF THE SEA (1970 - 1979)

CHAPTER NINE: EVOLVE WITH YOUR SPORT (1980 - 1989)

CHAPTER TEN: THE BEGINNING OF MODERN HISTORY (1990 - 1999)

CHAPTER ELEVEN: PERU: TOP LATIN AMERICAN SURFING POWER (2000 - 2009)