The arrival of the 1960s was a golden era for surfing around the world and in particular Peru. With the arrival of balsawood boards courtesy Eduardo Arena Costa, the supply of domestic boards manufactured by Luciano Montero and Gerhardt Schreier, along with a polyurethane foam board that a group of Hawaiian female fans gave to Carlos Rey y Lama in 1957, and the polyurethane foam boards that Hobie imported, the number of surfers had grown rapidly. Soon surfing was one of the most popular and successful sports in Peru.

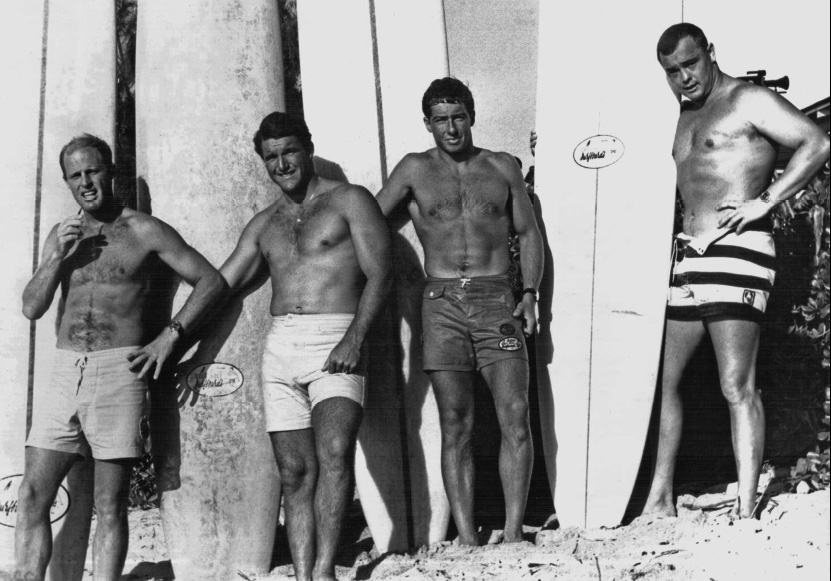

In the ‘60s Peru reached the pinnacle of the world surfing rankings thanks to names such as Héctor Velarde, Felipe Pomar, Joaquín Miró Quesada, Miguel Plaza, Francisco Aramburú, Gustavo Tode, Carlos Velarde, Sergio Barreda and Eduardo Arena. The ‘60s was also a period of adventurous exploration as Peruvian surfers searched their country for new breaks. They uncovered spots that are still widely ridden today: Cerro Azul, Punta Rocas, Pico Alto, La Herradura, Chicama and Bermejo.

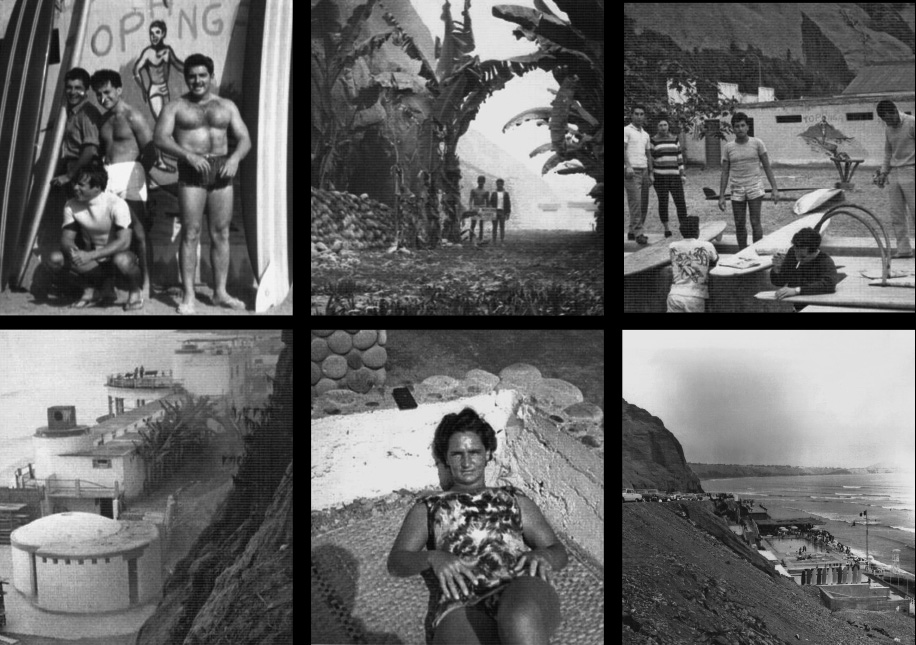

In the early ‘60s, the landscape of Lima was very different from what it looks like today. The Costa Verde Beach Circuit had not yet been built. The waves still died out at the shore of the Waikiki Club. Unlike today where they can simply drive from point to point, back then the surfers had to paddle to reach other surf spots. Beaches such as La Pampilla and Redondo required surfers to paddle long stretches. Nonetheless, the isolation of the various surf clubs that were popping up around Lima would soon end. Rafael Berenguel used to surf at the Agua Dulce Beach and Regatas Club, but one day when the surf was particularly big he rode a wave that took him across the bay until he reached the beach at Baños de Barranco. Club Topanga was in the process of being built and Berenguel found himself among a friendly group of surfers who he had not met before. He realized then that a lot of people around Lima had come down with the surfing fever.

Founded by the Barranco (a district of the city of Lima) surfers, Club Topanga had been functioning since 1956 and was much like their Miraflores (another district of the city of Lima) counterparts in the sense that they had to use the facilities of the municipal beach baths to store their boards. In 1961, Berenguel and Manuel Maldonado joined Club Topanga, which at that time was led by Alfredo De Paz. That same year members of Club Topanga merged with Club Makaha and thus the glory days of Club Makaha were underway. Over time, the links between the Lima surf clubs would strengthen and interclub tournaments were organized where surfers competed against one another. It all took on a very familial tone.

In the early ‘60s the dominance of balsawood boards started to decline. Polyurethane foam boards were quickly becoming the equipment of choice for a variety of reasons—mainly they were lighter, more maneuverable and easier to make. The first foam board reached Peruvian shores in March 1957. A gift for Carlos Rey y Lama courtesy of his Hawaiian female friends Betty Heldrich, Ethel Kukea and Ann Lamont, for some reason the board was not actually ridden until 1958. The first authentic surf brand to reach Peru with any regularity was Hobie. Imported by Alfonso Navarro Denegri, it was an immediate hit. Shortly thereafter, big wave pioneer Greg Noll sponsored Felipe Pomar and other brands including Baysee’s, Hansen’s, Jacobs’, Bunger’s and Hawaii Surfboards all got in on the action. Miki Dora’s “Da Cat” model was hugely popular and one can still find the board on display in Lima. There was also the Deportes Acapulco shop, which imported Ron and Keoki boards from Australia. Táter Ledgard brought the Cheater and Trestles Special by Harbour Surfboards in Seal Beach, California. “Modesto” Vega got his hands on John Peck’s Penetrator boards. The first surfer to get barreled backside at Pipeline, Peck had originally brought his boards down to Peru for one of the early championships. Luis Malpartida was responsible for the import of Gordon and Smith boards. Lucas Tramontana sold Rick and Brewer boards, while Alfredo and Carlos Málaga handled business for the Surfboard House. More surfboard brands found their way into the country in the ‘60s, but eventually when the military government came to power in Peru all imports ceased.

It didn’t take long for the first domestic shapers appear. The first dedicated surfboard craftsman was José Orihuela. Working with his brother, Ricardo, together they provided Peruvian surfers with an array of new polyurethane boards. The quality and maneuverability of these boards allowed for increasingly radical styles to develop. Gordo Barreda has explained that until 1967, Peruvian surfers still surfed on longboard that were typically about nine feet in length. Other board builders soon followed suit. Richard Malachosky and Nino Cicirello were other early shapers, as well as Dante Poggi who produced Paja Systems boards. Gustavo Reátegui made the Magus board. Wayo Whilar, Tato and Guayo Gubbins, Iván Sardá, Carlos Barreda and Fernando Ortiz de Zevallos were other notable shapers of the era. Together they contributed to a golden era in Peruvian surfboard building.

For all of these craftsmen it began with an introduction to board building by a famous Californian who lived in Hawaii named of Dennis Choate. He had partnered up with Aldo Fosca and together they manufactured boards in Lima under the label Pacific Surfboards. They worked on the rooftop of Aldo’s house and it was here that Peru’s would-be shapers learned their art.

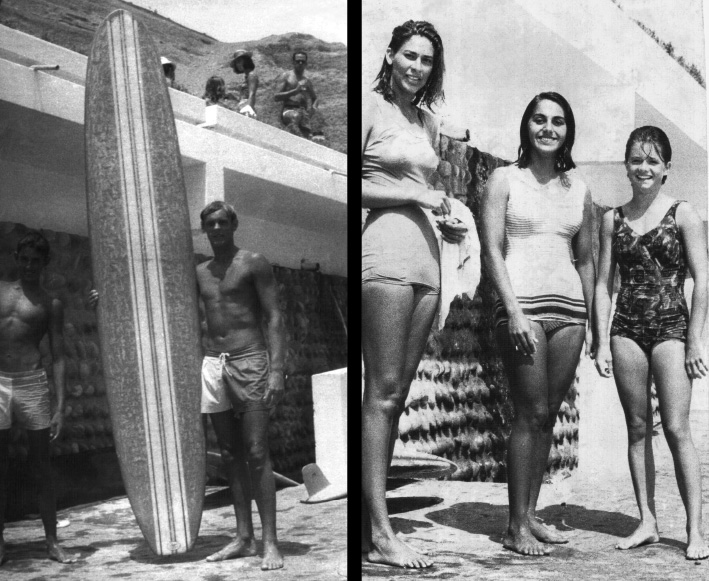

A small group of girls from Lima also started surfing in the ‘60s. They didn’t care to participate in the surfing contests, but rather enjoyed the adventure of surf and the connection they felt with the ocean in summer and winter alike.

“We surfed without wetsuits in wintertime and without leashes,” describes Jonchi Pinzas. “We walked downhill towards the Makaha and Waikiki clubs in the morning to surf because Mamiko lent us the club members’ boards. Then we walked past the small waterfalls to Barranquito at noon to surf the break line. What was really cool was to go down south of Lima, to El Silencio and Cerro Azul. I went to Pasamayo with Marjory Cannock, and before the opening of the international championship, Jimmy Blears and Corky Carroll lent us their boards. We surfed good waves. We were the first group of girls that went to surf in Chicama and during an exploratory trip in 1972, I stayed at the Cabo Blanco Fishing Club, and we were the first to surf what is now known as the Cabo Blanquillo.”

This first group of female surfers consisted of Sonia Barreda, her daughter Liliana Barreda, Ana María del Carpio, Marjory Cannock, Eva Terry and Jonchi Pinzas.

“I remember those days at Cerro Azul beach, when one was happy to hear the engine of a car from afar and you said to yourself, ‘Jonchi is here, cool!’” recollects Liliana Barreda. “I would grab my board and bordering the shore I would reach the point to meet with Jonchi, her brother and the gang of friends, all together enjoying the waves! We were all free…. Without any leashes nor wetsuits, no sunscreen and no people. Oh, by the way, the few girls that surfed back then had priority to catch a wave.”

In 1972, one of the first advertising films done in Peru featuring surfer girl was shot in La Pampilla. Jonchi Pinzas starred in it with her brother, Washington. It was a TV commercial for Audaces (meaning bold) cigarettes. The motto of the commercial: “They are bold.”

Since 1955, Peruvian surfers have embarked on an annual, six-mile speed paddleboard race between La Herradura and Club Waikiki. Every year the record seems to fall. In 1955, Albert Dowden paddled the distance in 55 minutes. The following year, Rabbit Kekai did the paddle in 44 minutes. Carlos Velarde, the winner in 1957, was the first Peruvian to have his name included on the trophy and made the paddle in 48 minutes. In 1960, California’s John Severson, the founder of Surfer Magazine, established an impressive record when he was able to break the time set by “Rabbit” Kekai and made it between the two beaches in barely 43 minutes. Severson, satisfied with his victory, was also thoroughly impressed by Héctor Velarde’s performance, who finished just one tenth of a second behind Severson. Year after year, the classic competition linking La Herradura with Waikiki brought together Peru’s best surfers.

To stand out in this competition one had to be in an extraordinary shape, but they also needed to have tremendous understanding of how the sea behaved. Overcoming the waves and defeating the currents was just as much a part of the test. The interesting thing was that when surfers had covered 95 percent of the distance and got to the Miraflores lineup they struggled to catch a wave that would allow them to finish the day by surfing it. In 1960, Severson and Velarde got to the surf line at the same time and caught the same wave, which they rode in all the way to shore, much to the appreciation of the fans cheering on the shore.

Not content with his narrow margin of victory against Velarde, in ‘61 Severson showed up in La Herradura and categorically won with a time of 46 minutes sharp. It wouldn’t be until ’63 that the record fell to a young Peruvian surfer. He plunged into the Herradura waters as if he were fleeing an earthquake. He crossed the Salto del Fraile ridges like a fish. He passed in front of the Regatas Club like a sailboat and reached the Waikiki standing up, majestically surfing to shore on a magnificent wave to finish in the astounding time of 41.5 minutes. This boy, whose smile was portrayed in all the newspapers of Lima, was 18-year-old Felipe Pomar.

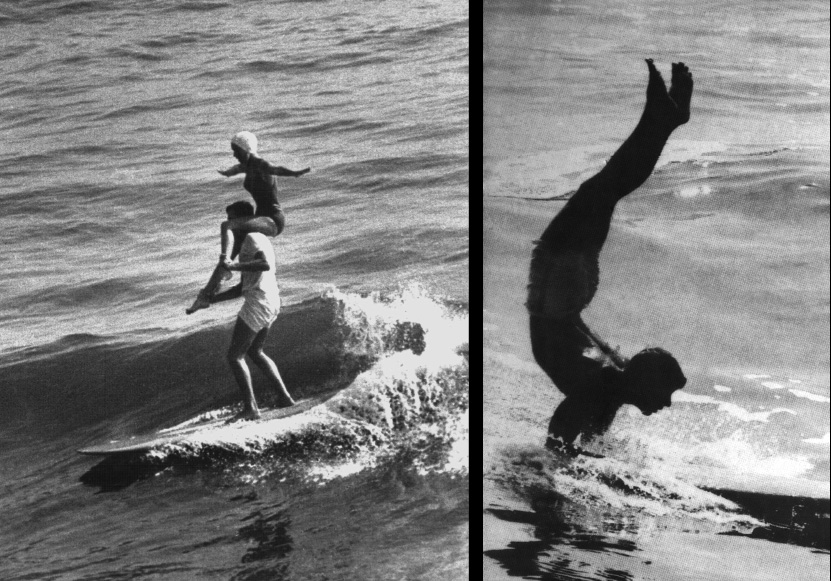

On December 7 1962, Club Waikiki celebrated its 20th anniversary in grand style. Under the guidance of president Carlos Rey y Lama, and largely thanks to the rules introduced by George Downing in the ’50s, Peruvian surfers took part in a wide array of celebratory competitions. There was the infamous paddleboard race from La Herradura to Waikiki, punishing 1,000-meter races, the stylish tandem stunts, the exciting relay events and the most popular small wave skills events. Besides being experienced big-wave surfers, Peruvian surfers flourished in the smaller conditions, inventing and developing a repertoire of maneuvers, which surprised everybody. They performed stunts surfing such as riding a wave while sitting on a chair mounted to a surfboard or riding waves while standing on their heads.

In 1962, the founders of Club Waikiki decided they wanted to establish a new milestone. Born from conversations at sea, they decided that organizing the first world surfing championship was their calling. Never before had an event of this nature taken place, and Peruvians, who were by then a world surfing superpower, decided to organize a championship to assemble the most elite surfing talent in the world.

The Peruvian National Surfing Commission was founded on January 26, 1962. Almost immediately they convinced the Peruvian Sports Committee to recognize surfing as a Peruvian sport and support the idea of a world championship. Carlos Rey y Lama addressed a letter to Luis Marrou Correa, President of the Peruvian Sports Committee dated August 26, 1961. In the letter he explained that Club Waikiki was about to celebrate its 20th anniversary and that there was a significant amount of people practicing his sport. He also noted all of the new clubs similar to Club Waikiki were being founded around the country. He explained how kids under the age of 14 and women practiced the sport. He told of new surf points that had been discovered in Cerro Azul and Pasamayo, as well as Huanchaco further up north near Trujillo. Finally, the letter mentioned that there was a project to organize the world championship, which sought to convene the best surfers of Hawaii, California, Australia, France and South Africa. It was these reasons that prompted the members of the Club to submit an application in order to “cooperate with sports in general, and to ensure that surfing would be considered a sport recognized by the committee in order to form the Peruvian National Surfing Commission.” The letter (kindly provided by Carlos Rey y Lama as research material for this book) is very interesting because it shows how popular surfing had become in only 20 years, stating that in 1961 there were already over 300 surfers in Peru.

Some surf historians point to the first world surfing championship taking place in Australia in 1964. Others note that it was the world surfing championship that took place in Peru in 1965 was the first “official” championships. Until today, however, the world championship held in Peru in 1962 had rarely come up.

The newspaper clippings from 1962 hold many surprises. El Comercio, La Prensa (two daily Peruvian newspapers at that time) and other media of the time refer to the championship as the first world championship. Of course, some might argue that as it was the Peruvian press that covered this event and it is only natural to think that they would have believed themselves to be the first to organize such an event. However, in a February 1962 edition of the French newspaper Le Monde it is states that a delegation of French surfers traveled to Peru to attend the first world surfing championship.

In the valuable files of Carlos Rey y Lama there is further proof. Thanks to these documents we can identify the first president of the Peruvian National Surfing Commission as the legendary Alfredo Granda, whose achievements were described in the previous chapter. These achievements took a new turn when he decided to head the organizing committee of the first world surfing tournament. The idea was to present a true Peruvian delegation to which members of other clubs were invited. That is why the names of Alfredo Alvarez Calderon, Luis Arguedas, Andrés Aramburú and Raul Risso deserve special mention. They represented the Waikiki, Makaha and South Pacific clubs, and together with Rey y Lama decided to extend invitations to teams from Hawaii, California, Australia and France. These powerful surfing nations made up the core of the international sport and the idea was to bring them together in one global championship event.

While a multitude of Peruvian surfers were endlessly working out in sessions that were taking place in Miraflores, Kon-Tiki and Pasamayo, invitations were extended to the world surfing powers.

The answers came quickly. Hawaii decided to send its new champion Jose Angel, while California selected John Severson, Mike Diffenderfer and Kenneth Kesson. Australia decided to participate in the first world championship with a delegation made up of the legendary Bob Pike and Michael Hickey. In France, the club founded in Biarritz by Carlos Dogny, chose Jacques Roth and Joaquin Moraetz to represent them.

There was much media attention paid to the impending event and the local newspaper El Comercio made note of the Peruvian surfers’ workout program and the championships held at Kon Tiki. It reads: “Lovers of the sport have faced eight meter high waves with a top speed of 80 kilometers per hour. The fall from a wave of this height is compared to the feeling you would have after falling from a five-story building.”

Besides the incredible story it tells, this news excerpt is extremely valuable because it spells out in detail the intensity of the Peruvian surfers’ commitment in preparing for the upcoming competition and the visiting surfers.

Over the years the waves at Kon Tiki had been taken on by a legion of big wave surfers. Disciples of “The Three Musketeers,” they all knew that the decisive moment of the competition would take place at that surf point. Surfing fever was running rampant amongst Peruvians, men and women alike, and in January and February of 1962 the Peruvian press published articles alleging that Gladys Zender, the Peruvian Miss Universe 1957, was considering participating on the national women’s team. Thousands of people took to the beach hoping to catch a glimpse of her in her bathing suit. But she certainly wasn’t the only beauty on the beach. Manie Rey, Eve Eyzaguirre and Pilar Merino, all enjoyed the waves together. Along with Sonia Barreda, Ive Kessel, Olga Pardo, Carmen Velarde Pastorelli and Lucha Velarde the Peruvian women’s surf moment was a force to be reckoned with.

When it came time for the world champion there were several marquee events scheduled in the spirit of the rules established by George Downing on his 1954 visit. It was decided that there would be a 1,000-meter race for the founders in which Carlos Dogny Larco, César Barrios, Jorge Helguero and Carlos Origgi participated. There was also a 2,000-meter event, which was open to all participants, and another event, as well as a 4 x 2,000 meter relay. The relay required teams of four people, but because of the lack of surfers in the contest organizers had to mix and match the competitors into three teams. The Californian surfers, John Severson, Mike Diffenderfer and Kenneth Kesson, were joined on the same team as José Angel from Hawaii. Together they represented the United States. Australian surfers Bob Pike and Michael Hickey joined forces with France’s Jacques Roth and Joaquin Moraetz to form the second team. And finally, there were the Peruvians, which consisted of Carlos Velarde, Héctor Velarde, Francisco Aramburú and Felipe Pomar. Peruvian Héctor Velarde became the first world surfing champion thanks to his commitment and tenacity, allowing him to gain the necessary points thru the whole contest.

Other events scheduled for the world championship included the classic endurance paddleboard race between La Herradura and the Waikiki Club and the tandem championship, in which the different pairs of competitors aimed to perform the most striking maneuvers. Foreign surfers that did not have partners surfed this event accompanied by Peru’s agile female surfers. Two small wave events were programmed at the Waikiki and Pasamayo surf breaks. They would serve as a preamble to the big-wave event programmed to take place in the turbulent Kon Tiki waves. Finally, the championship would be decided by a thrilling 200-meter race.

Each of these events required its own unique scoring and required the diligence of a knowledgeable panel of judges. For example, the winner of the Kon Tiki big-wave event could get a maximum of 10 points, while the winner of the 200-meter sprint would be given six points. The world champion would then be the person who managed to get the highest score by adding up all of their points at event’s end. The winners of each event would be crowned world champion in their respective disciplines, but the grand championship was designed to crown the most complete surfer.

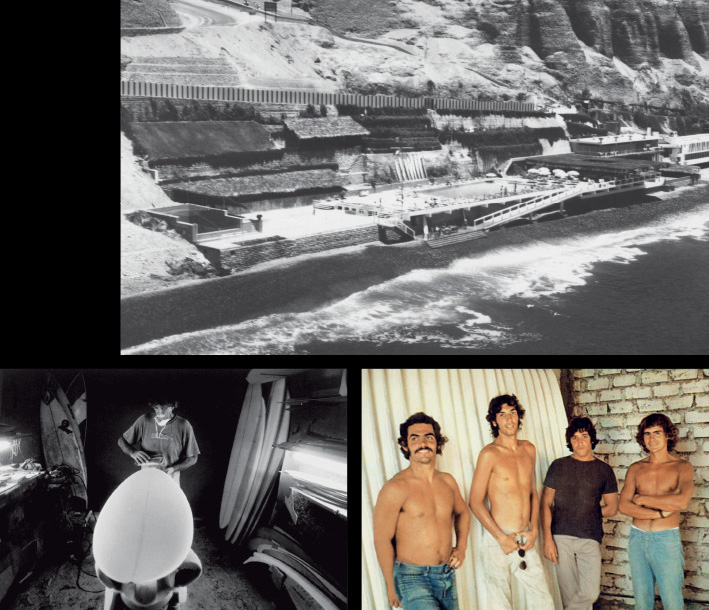

Leading up to the championship the Club Waikiki management invested over one million soles in renovations and improvements on its main building, which allowed them to dazzle their guests with beautiful facilities facing looking out over the pleasant sea of Miraflores. Local newspapers reported how each surfer’s training was progressing and the press even covered the pre-tournament activities. On February 17, 1962, the press gathered at the Villa Country Club to witness a demonstration put on by a number of skilled surfers. This event, which had nothing to do with the championship, served as a thermometer to not only measure the skills of the different competitors, but also the public’s reaction, which filled the shores of Villa while surfers attempted to tame the explosive closeouts. A few yards from the shore there is a devastating closeout, which on good days can be over16 feet high. Up close the surfers looked like real kamikazes. Bob Pike took the win with John Severson finishing a close second. Mike Hickey, Mike Diffenderfer, José Angel, Jacques Roth and Joaquin Moraitz also participated.

One of the most pleasant surprises of this competition was the incredible amount of surfers who represented Peru. The list includes: Felipe Pomar, Héctor Velarde, Carlos Dogny, César Barrios, Jorge Helguero, Carlos Origgi, Guillermo Wiese, Eduardo Arena, Augusto Felipe Wiese, Francisco Aramburú, Fernando Costa, Leoncio Prado, Felipe Beltrán, Luis Caballero, Gustavo Tode, Rafael Navarro, Roberto Tode, Héctor Velarde, Max Peña, Carlos Velarde, José Peña, Mariano Prado, Felipe Pomar, Joaquín Miró Quesada, Carlos Ferreyros, Dennis Gonzáles, Fernando Arrarte, Alfredo Hohaguen and Richard Fernandini. Notably absent was Federico “Pitty” Block, who was in Chile representing Peru in a car race.

On March 10, 1962, the President of Peru, Mr. Manuel Prado Ugarteche, accompanied by his wife, Clorinda Málaga Prado, visited Club Waikiki to inaugurate the first world surfing championship. Smiling widely, expressing supreme satisfaction, the following surfers appear in many photographs from that day: Carlos Rey y Lama, Carlos Dogny, César Barrios, Enrique Prado and Carlos Origgi, in addition to Guillermo Wiese, Eduardo Arena, Alfredo Benavides, Augusto Felipe Wiese, Mariano Prado, Eric Rey de Castro, Javier Broggi, Carlos Tudela, Alfredo Hohaguen, Alfonso Miró Quesada, Raúl Risso and Frank Tweedle, among others. They were the privileged few to accompany the President as he toured Club Waikiki’s revamped facilities, explaining the most remarkable details of the organization of the championship.

Peru’s first world champion was Francisco Aramburú, still just a teenager at the time. He managed to beat thirty rivals in the dynamic 2,000-meter paddle race. The newspapers reported that the speed reached by Aramburú was surprising to the point that many thought this young man, destined to become one of Peru’s great surfers, had moved with the speed and ease of a dolphin. The results of the event were:

2,000-METER PADDLEBOARD RACE

1. Francisco Aramburú 10 points

2. Héctor Velarde 8

3. Carlos Velarde 6

4. Bob Pike (Australia) 4

This win was followed by other significant Peruvian victories, such as the one achieved by Felipe Pomar when he set a new record of 41 minutes and 30 seconds in the endurance paddleboard race between La Herradura and Waikiki, handily beating Francisco Aramburú, Bob Pike and Héctor Velarde:

ENDURANCE PADDLEBOARD RACE FROM LA HERRADURA TO WAIKIKI

1. Felipe Pomar 41´30” 14 points

2. Francisco Aramburú 42´30” 10

3. Bob Pike (Australia) 42´31” 8

4. Héctor Velarde 43´15” 6

In the 4 x 2,000-meter relay event, the Peruvian surfers were outstanding, obtaining first and third place, blowing their foreign rivals out of the water:

4 X 2,000 METER RELAY

1. H. Velarde, C. Velarde, F. Aramburú, F. Pomar 12 points

2. M. Diffenderfer, M. Hickey, J. Angel, B. Pike 8

3. G. Costa, J. Miró Quesada, M. Peña, A. Mulanovich 6

The only event where Peruvians did not win was the 1,000-meter tandem race, where Hawaiian José Angel, thanks to the incomparable grace of Manie Rey (who was Héctor Velarde’s steady partner) won first place. This was another example of the sportsmanship of the Peruvian Team and Manie Rey, who raced with Angel. Manie was considered the most talented mermaid in the Peruvian tandem scene and shared the honors of being world champion with the Hawaiian. Viewers of this unique day describe that Manie Rey’s figures were only comparable with the grace of a fairy tale princess. The judges, impressed with the couple’s speed, unanimously awarded them the title:

1. José Angel, Manie Rey 6 points

2. Alfredo Paz, Pilar Merino de Paz 4

3. John Severson, Louise Severson 2

In the small-wave event, Leoncio Prado, a descendant of a Peruvian war hero, stood out, as he surprised everyone and was crowned world champion by solidly beating Héctor Velarde and Californians Mike Diffenderfer and Kenneth Kesson.

1. Leoncio Prado 10 points

2. Mike Diffenderfer (California) 8

3. Héctor Velarde 6

4. Kenneth Kesson (California) 4

In the tandem event, Héctor Velarde and Manie Rey won another world championship by performing a dance of unspeakable beauty on the water. They categorically beat the tandem couples of Severson and his wife and the legendary Carlos Dogny and Carmen Pastorelli.

1. Héctor Velarde, Manie Rey 8 points

2. John Severson, Louise Severson 6

3. Carlos Dogny, Carmen Pastorelli 4

After running the gauntlet through these events Héctor Velarde sat in a promising position to win the coveted world championship. There were, however, other events that did not score points for the world championship, but added to the overall spirit of the championship.

In the women’s 200-meter race, Pilar Merino barely edged out Ive Kessel, Olga Pardo and Lucha Velarde. In the women’s 500-meter race, Sonia Barreda, mother of Gordo and El Flaco Barreda, beat Pilar Merino and Manie Rey, demonstrating that her children had inherited her extraordinary competitor’s skills.

In the men’s specialty 1,000-meter race, designed exclusively for founders, Carlos Dogny showed his legendary experience once again when he beat friends Enrique Prado, Carlos Origgi and César Barrios. Afterwards the spectators gave the men a five-minute standing ovation.

In the men’s open 1,000-meter race there were 67 surfers entered. Felipe Pomar emerged victorious, beating Max Peña and Augusto Mulanovich. This meant that with one final event to go, Pomar and Francisco Aramburú were the only two surfers capable of threatening Héctor Velarde’s absolute supremacy. There were only two point-scoring events left and Velarde was sitting on a comfortable nine-point lead.

1. Héctor Velarde 32 points

2. Felipe Pomar 23

3. Francisco Aramburú 23

4. John Severson 8

By this stage in the world championship both the press and the competitors were focused on the impending big-wave event at Kon Tiki on March 19. For obvious reasons this event was weighted more than the others with more points on the line or a win. Plus, they were being followed by a huge number of adoring fans and didn’t want to disappoint in the massive waves of Kon Tiki.

Velarde knew perfectly well that he needed a good result in order to stay in the forefront, and Felipe Pomar, the most skilled surfer at Kon Tiki at the time (he had recently won a national tournament here) was a dangerous rival. As the morning of the final dawned the waves were at their best. Sets were topping out at an upwards of 12 to 15 feet and the Peruvian surfers applied their local knowledge with devastating effect. They held the top three spots of the tournament thanks to their skilled and risky maneuvers, but Felipe Pomar had not been able to catch a good wave and show off his skill.

With only six minutes remaining in the contest Felipe paddled into the wave of the day. He drew a risky line, executing his maneuvers to perfection. John Severson exclaimed, “God damn!” Pomar came to shore with a huge smile beaming across his face. He was immediately hoisted onto the shoulders of his friends and carried up the beach. Without question the best surfer at Kon Tiki on this Sunday in 1962 was Felipe Pomar. Gustavo Tode finished second and Héctor Velarde got third place, which kept him in the lead for the championship.

1. Felipe Pomar 16 points

2. Gustavo Tode 12

3. Héctor Velarde 10

4. John Severson (California) 8

With his result at Kon Tiki, Pomar was sitting with 39 points, while Velarde had a total score of 42 points. The championship would go to one of them, but first, one final test. The 200-meter sprint was the last final event before surfing’s first world champion could be crowned.

The Velarde brothers swept into first and second with Carlos taking first and Héctor finishing second. Pomar finished third, and like that Héctor Velarde was crowned the first world surfing champion.

1. Carlos Velarde 6

2. Héctor Velarde 4

3. Felipe Pomar 2

1. Héctor Velarde 46 points

2. Felipe Pomar 41

3. Francisco Aramburú 23

4. John Severson (California) 16

5. Carlos Velarde 15

6. Bob Pike (Australia) 14

7. Gustavo Tode 12

8. Mike Diffenderfer (California) 10

9. Leoncio Prado 10

10. José Angel (Hawaii) 8

11. Carlos Dogny 4

12. Kenneth Kesson (California) 4

13. Max Peña 4

14. Mike Hickey (Australia) 2

15. Augusto Mulanovich 2

Dominating most of the disciplines, Team Peru was crowned the number one world surfing power.

1. Peru 166 points

2. United States 38

3. Australia 16

4. France 0

Inspired by the world championship that had taken place in Peru in 1962, the Australians decided to follow suit and invite the world to come surf Down Under. The Australian Surfriders Association (ASA) was founded in 1963 in Sydney by Bernard “Midget” Farrelly (its first president), John Witzig, Stan Couper, Ross Kelly and Ray Young. This new organization’s goal was to bring together the best surfers of the world and celebrate a world championship tournament in Sydney, Australia, in 1964. Surfer entrepreneur Bob Evans, creator of the Surfing World magazine (founded in 1962) and a surf movie producer, assisted with the organization, securing sponsorship from Ampol Petroleum Limited.

As the 1962 world champion, Héctor Velarde received an official invitation from the ASA to participate in the tournament, which ended up being called the World Titles Sydney 1964. On the terrace of Club Waikiki, Velarde decided to invite a member of the club to accompany him as his father had given him two tickets as a reward for his great victory in the 1962 world competition.

“Who’s coming with me?” asked Velarde in the Club, raising both tickets with one hand.

Eduardo Arena Costa, the champion of the first big wave international tournament organized by the club in 1956, raised his hand and accepted the generous offer. In an exclusive interview, Arena told the story of the world championship that took place in Australia in which surfers from California, Hawaii, Australia, France and Peru participated.

Held in Sydney on May 16 and 17, 1964 and the eventual winner, sometimes referred to as surfing’s first world champion, was Australian Bernard “Midget” Farrelly. For their part of the festivities the Peruvians found a favorable atmosphere. It was here that the surfers that had been invited began to entertain the idea of forming an international federation that could organize the different surfing nations and sanction events. The idea was greeted with enthusiasm by Arena, who contributed so many good ideas that he was elected president of the new organization. Arena boldly announced that the first official world surfing championship would be organized in Peru in 1965, with rules created and approved by the founding nations of the International Surfing Federation (ISF). He led the organization until 1972.

In 1965 the ISF took a number of steps forward in the development of an international world championship. For starters, they made a move to utilize a panel of international judges (one from each country): Peru, Australia, United States (Hawaii and California), South Africa and France. Additionally, all competitors would travel to Peru with tickets being paid for by the ISF, while their lodging and living expenses would be paid for by the host country, Peru. It was possible to organize, for the first time in surfing history, a legitimate world championship recognized by every participating nation.

The first activity undertaken by ISF President Eduardo Costa Arena was to ask each country to found their national federation and elect their representatives so they could prepare to compete in the 1965 world championship in Peru.

In Pancho Wiese’s home in February 1965, under the eye of a notary public, that the International Surfing Federation (ISF) was formally founded. Eduardo Arena was named president and Luis Caballero was named secretary (an important task still pending today is to find the original document, the minutes of the foundation of the ISF signed by the representatives of the nations). It was the intent of the ISF to establish and standardize the regulations that would allow the organization of world surfing championships based on previous experiences in Peru in 1962 and Australia in 1964.

Back in 1964 during the farewell cocktail reception that was held for all the participants of the world tournament in Sydney, Eduardo Arena announced that Peru would host the first world championship organized by the ISF. His proposal was met with great excitement from the invited teams. The surfers of those days were very much aware of the place that Peru held within the surfing world, and taking into account the experience of the 1962 World Championship, there was no reason to doubt the imminent success that its organization would have with Arena in charge.

But one huge hurdle that Arena and his team had to overcome first was raising the necessary funds for the ’65 championships. Thanks to the collaboration of various institutions like: El Comercio (Peruvian daily newspaper), Pepsi Cola, Lobitos Petroleum Company, Aerolíneas Peruanas (former Peruvian Airlines), the Tourism Corporation and the Peruvian Sports Committee, the group chaired by Eduardo Arena accomplished the impossible. Thanks to the help of these sponsors, Peruvian surfers would be able to write a glorious chapter in the history of South American surfing.

Arena’s admirable organizational skills eventually led him to the headquarters of the NBC TV Company in New York. After hearing his pitch and seeing Arena’s commitment to the spectacular event they did not hesitate to provide their full support. Surfing had already captured the imagination of a large number of people in the United States, and NBC executives were astute in sensing that the value of the global event.

Meanwhile, the efforts of the International Surfing Federation continued moving forward. Each country was able to found their respective national associations to represent them. In those early days communication was not nearly as instantaneous as it is today. Arena had to rely on a telex machine through a hard-working operator to get his correspondence across. With countries as far away as Australia, South Africa, France and the United States, it was no easy feat.

In a recent conversation at his home in San Isidro, Lima, Arena noted that one day the operator, intrigued by the numerous calls that he had been receiving from some of the world’s most remote corners, could not help himself from asking him, “Sir, who are you?”

The operator must have imagined Arena to be an important government official, a consul, or a cultural attaché. In fact, he was just a surfer, but by overcoming all the communication hurdles, and fostering a sense of community among all of the groups of surfers around the world, Arena created a sense of belonging to the newly formed international body. By the end of the process nine countries had raised the level of their surfers to the official category of “sport representatives.” This elevation of personnel was essential to the development of surfing on a more official level. From this point on, it was possible to speak of national teams and the colors of the various flags convened by the ISF.

One of the major concerns of the new ISF was to choose the most suitable venue for the world championship. Naturally, the members of the Peruvian team immediately thought about the Kon Tiki point. It had been the successful setting of other international championships and the waves had the necessary qualities to test the skills of the various participants: size, endurance, perseverance and speed.

But Kon Tiki presented a number of serious difficulties. For starters, the judges did not have a suitable place to watch and carry out their scoring duties. Secondly, there was nowhere for the public to come and watch the best surfers of the world compete. The surfers were stuck in the middle as a heated discussion about the most important event in surfing’s history ensued. The advantages and disadvantages that Kon Tiki offered were weighed back and forth until it was finally decided to move the championship to Punta Rocas. The break had only just been pioneered and ridding for the first time in 1964 by an Australian globetrotter named Peter Troy and a Peruvian by the name of Rafael “Mota” Navarro. The beach at Punta Rocas, which when translated means “Rock Point,” had a natural esplanade that would facilitate the judges’ work and would allow the public to enjoy the show. It fit the criteria, but questions remained.

On a warm summer afternoon in 1964, Rafael Navarro and Peter Troy, who had just been eliminated in the semifinals of the Kon Tiki Big Wave International Championship, paddled out at Punta Rocas for the first time. Although Peruvian surfers had seen the break from a distance, up until this point no one had been crazy enough to try and surf them. The waves literally crashed against the rocks, covered with slippery seaweed, sea urchins, barnacles, limestone formations and sharp shells. Just the thought of surfing the place was through of as a suicidal act. Surfers did not have leashes attached to their board at the time, which made any attempt to ride it all the more harrowing. People that watched Navarro and Troy paddle towards the dreaded point prayed that the insane act that these two guys were about to perform would not lead them to a gruesome death.

According to accounts from that day, the set waves at Kon Tiki were topping ten feet, which would have made the seas quite lively. Héctor Velarde remembers that the people stationed on the esplanade at Punta Rocas numbered in the dozens. They would have seen Mota and Troy master the huge waves, trying their best not to fall off.

With surfers from the United States, Australia, France and South Africa, the ISF commenced the first world surfing championship on the February 18, 1965. The rules stipulated that only the big wave competition would grant points to surfers. Unlike previous championships, the focus would be on judging the athlete’s skill on waves without considering the scores accumulated in other events, such as tandem, paddle races or relays. With four foreign judges and one Peruvian judge, surfers were scored according to four criteria: the highest speed on a wave, the longest route, the location in relation to the most critical part of the wave, and the best maneuvers. The teams of each nation were represented by the following surfers:

PERU: Felipe Pomar, Gustavo Tode, Héctor Velarde, Rafael Navarro, Pancho Aramburú, Joaquín Miró Quesada, Luis Miró Quesada, Carlos Velarde, Leoncio Prado, Sergio Barreda, Miguel Plaza, Manolo Mendizábal, Javier Paraud, Dennis Gonzáles, Rafael Hanza, Carlos Barreda, José Peña, Germán Costa, Max Peña, Julio Ratto, Carlos Aramburú.

HAWAII (UNITED STATES): Richard Keaulana, Bobby Cloutier, Bunny Aldrich, George Downing, Fred Hemmings, Joey Cabell, Paul Strauch, Chuck Shipman.

CALIFORNIA (UNITED STATES): Mike Doyle, Richard Chew, Robert August, John Severson, Phil Edwards, David Nuuhiwa, Mark Martinson, Jim Graham, Mickey Muñoz, Bill Fury, Danny Lenehan, Bo Boeck, Tim Dorsey, Chuck Linen, Steve Bigler, A. Grimstad, J. Schaffer, Richard Harbour.

EAST COAST (UNITED STATES): William Whitman, Thomas Grow.

AUSTRALIA: Peter Troy, Nat Young, Midget Farrelly, Bob Evans, Ken Adler, Rodney Sumpter.

FRANCE: Philippe Gerard, Joel De Rosnay.

SOUTH AFRICA: Max Wetteland, Anthony van der Heuvel, John Thompson.

The best surfers in the world convened for the first time to compete based on rules approved by the ISF, which made the event official, a characteristic that the former world events had lacked. The President of the Republic of Peru, Mr. Fernando Belaúnde Terry, kick started the championship at Club Waikiki. Two events that did not award points, but served to measure the competitors’ strength. The first event was a 2,000-meter paddle race. The second was a mixed tandem demonstration. The results were:

1. Felipe Pomar 1. Mike Doyle – Linda Merril

2. Anthony Van Der Heuvel 2. Jim Graham – Heather Edwards

3. Pancho Aramburú 3. Héctor Velarde – Olga Pardo

From the very start, Felipe Pomar showed himself to be one of the toughest of all participating surfers. When the surfers embarked on the six heats that were held at Punta Rocas they were greeted by a raging sea. Fog caused the competition to be put on hold for several hours. When it cleared it revealed waves an upwards of 12 to 15 feet crashing into the point. Only 18 surfers qualified for the semifinals: five Hawaiians, six Californians, three Australians, three Peruvians and one South African. The representatives of France almost died. They were literally thrown against the rocks of the shore and completely knocked out of the competition. Hawaiians Richard “Buffalo” Keaulana, Bobby Cloutier, George Downing and Paul Strauch, won four of the six heats that were held on the first day of competition, while Hawaiian Joey Cabell and the Peruvian Héctor Velarde both won their heats. The scores obtained by each of the eighteen semi-finalists were:

1. George Downing (USA) 229

2. Héctor Velarde (PERU) 219

3. Richard “Buffalo” Keaulana (USA) 219

4. Joey Cabell (USA) 216

5. Paul Strauch (USA) 213

6. Ken Adler (AUSTRALIA) 211

7. Mike Doyle (USA) 207

8. Anthony Van Der Heuvel (SOUTH AFRICA) 200

9. Bobby Cloutier (USA) 200

10. Robert August (USA) 199

11. Fred Hemmings (USA) 199

12. Felipe Pomar (PERU) 198

13. Mickey Muñoz (USA) 196

14. Nat Young (AUSTRALIA) 194

15. Midget Farrelly (AUSTRALIA) 191

16. Richard Chew (USA) 187

17. Gustavo Tode (PERU) 163

18. Danny Lenehan (USA) 152

On Sunday, February 21, the finals were held in even more terrifying conditions. Overnight the sea had grown even bigger with waves topping out in the 16- to 18-foot range and producing a deafening roar that completely shocked the spectators. The 18 remaining competitors were divided into two groups that would compete in two semifinal heats. The heats would last 75 minutes each, and the surfers were to be rated on their five best waves. Only four of the nine participants in each heat would continue on to the final. While Gustavo Tode and Hector Velarde were lost out by the slimmest of margins, Felipe Pomar was the only Peruvian who managed to accumulate enough points to stay in the competition.

1. Paul Strauch (USA) 355 1. Fred Hemmings (USA) 317

2. Nat Young (AUS) 353 2. Ken Adler (AUS) 312

3. Felipe Pomar (PERU) 331 3. George Downing (USA) 309

4. Mike Doyle (USA) 317 4. Mickey Muñoz (USA) 308

All the surfers interviewed for this chapter agreed that they had never seen such big waves in their lives at Punta Rocas. In the afternoon, before the eight survivors were locked in the final fight, the waves were averaging 12 to 15 feet.

In the final heat, with only a few minutes to go, Felipe Pomar Rospigliosi caught the biggest wave, a real beast, which the Peruvian surfed with strength and style. In the end Pomar was proclaimed the first official world champion—a ruling that was endorsed by four of the five judges. The movie produced by NBC was broadcast in the United States and the reaction of the American viewers was such that NBC was forced to retransmit it from coast to coast, an unprecedented event in the history of American television.

1. Felipe Pomar (PERU) 62 71 64 72 74: 343

2. Nat Young (Australia) 61 77 63 71 70: 342

3. Paul Strauch (USA) 61 74 63 71 70: 341

4. Mickey Muñoz (USA) 61 70 59 70 67: 327

5. Fred Hemmings (USA) 54 69 65 65 71: 324

6. Mike Doyle (USA) 58 71 59 66 70: 324

7. George Downing (USA) 54 66 52 63 65: 314

8. Ken Adler (Australia) 59 66 52 63 65: 305

You can see from the scores for each surfer that Pomar earned the highest score of the day with his last wave; the biggest wave in the final heat. He won the championship by merely one point, which indicates how close the competition was. In issue number 4 of Tablista Magazine, Pomar explained, “In my opinion, what allowed me to win the world championship was not that I was the best surfer of the world at that time. I think that I reached my surfing best between the years of 1966 and 1971, nevertheless in 1965; I was a good enough surfer to reach the final. I was in better shape than anyone else, and besides, I was convinced that I had worked harder than anyone else, and I had worked harder than anyone to be there. At that moment, I told myself: ‘You deserve this more than anyone else, because you got out of bed during months at 4 o’clock in the morning, you surfed when there were small waves and you also surfed when there were big waves. You sacrificed yourself. You did not have fun. You did not party.’ Then I told myself once I was in the final: ‘Nobody deserves this more than you, and I was in shape in order to face the challenge.’”

Thanks to the huge success of the ISF’s first world championship held at Punta Rocas, Eduardo Arenas demonstrated that surfing was a sport that could attract the attention of the whole world. Through his efforts Peru was able to attract and host the best surfers on the planet. Arena was instrumental in developing the standardized system of rules to judge the performances of the competitors. He was also able to secure the necessary sponsorship support to cover the expenses of the championship. For nearly a decade (1964 – 1972) Eduardo Costa Arena dedicated himself to the sport of surfing, helping it become one of the most recognized sports in the world.

In 1966, the enthusiasm unleashed by the first world championship at Punta Rocas inspired a desire to replicate the experience. This time it was California’s turn to host the world and the American delegates invited the best surfers and judges from each country.

Unfortunately Peru wouldn’t be as victorious as they were at Punta Rocas. Arena explains that during the week of competition the Peruvian contingent had been looking for waves up and down the coast and when the championship was finally called on the small waves at the San Diego beach did not favor the Peruvians, who in those days were characterized as big-wave specialists.

The Peruvians were used to surfing the powerful, open-ocean swells at spots like Punta Rocas, Cerro Azul, Kon Tiki and Waikiki, but the Californian championship was held in small, playful beachbreaks. Besides just the waves, the Peruvians also had the wrong equipment. Their boards were too big and cumbersome to work efficiently in the weaker waves (Gordo Barreda surfed on a 9’5”). Carlos Barreda, El Flaco, Peru’s small wave specialist, was the only person that was able to stand out. The Peruvian team was comprised of: Sergio and Carlos Barreda, Oscar Malpartida, Héctor Velarde, Miguel Plaza, Raymundo Salazar, Lucho Miró Quesada and Ricardo Bouroncle.

The trophy that Felipe Pomar had won in 1965 (the Eduardo Arena World Surfing Trophy) would go to a new champion. When the spray finally settled it was Australian Nat Young who stood atop the podium (he finished second in 1965. Once again NBC covered the event from start to finish, and although this championship differed greatly compared to the one held in Peru, it was broadcast from coast to coast in the United States to rave reviews.

After the Championships in 1966 the ISF made the decision to hold their event every other year (which meant Young had the privilege of holding onto the trophy for two years). In 1968, Puerto Rico was selected as the next location for the third world surfing championship. Eduardo Arena doubled down on his efforts to organize a truly great contest. Six competitors would have the privilege of representing Peru: Felipe Pomar, Miguel Plaza, Héctor Velarde, Fernando Ortiz de Zevallos, Sergio Barreda and Ricardo Bouroncle. NBC’s tremendous success broadcasting the previous two championships drove ABC—NBC’s rival—to offer US$8,000 in sponsorship money. NBC made a counter offer, but as it was lower than its rival’s and Arena opted to work with ABC.

The lush vegetation of Rincon—a reef break on Puerto Rico’s north shore—its crystal clear water and the high-quality waves that broke during the contest were the basis for producing another successful documentary. Transmitted from coast to coast in the United States, it ended up airing on five separate occasions—unusual coverage for any sport.

The overall winner of the tournament was the Hawaiian Fred Hemmings, who took the Eduardo Arena World Surfing Trophy with him to The Outrigger Canoe Club in Waikiki, where it was displayed until 1970. The Peruvians did not fare as very well, though Eduardo Arena’s impeccable organizational skills did get him reelected as ISF president.

In the early days there were a few attempts to ride waves around the Las Delicias area in the north, but armed with nothing but their bulky, wooden boards, it would take Guillermo Larco Cox, Carlos Dogny Larco’s cousin, and Guillermo Ganoza Vargas awhile to breakthrough up there. Things started to develop up north as a group of surfers led by Rafo Otoya in Huanchaco (next to the larger city of Trujillo) began to get more involved. Rafael Otoya Silva used to live in Lima and had learned to surf at Barranquito, with Joaquín Miró Quesada, Ernesto Barrón and Willy Ramsey. He bought a House surfboard and took it with him to Huanchaco in 1964.

A small group of enthusiasts accompanied him in his first adventures in the small bay area known as La Curva. The group consisted of: Lucho Ganoza, Rafo’s brother Roberto Otoya, Domingo Álvarez Calderón (who had also bought a Hobie surfboard), Cuté Ganoza and Beto Landeras. They were the first surfers from Trujillo to really dedicate themselves to surfing. They started working out on a daily basis and really focusing on the sport. They were the kings of the beach and served as inspiration for the younger generation, who in order to emulate them also started surfing.

In 1969 the second generation of Trujillo surfers emerged: Marielena Bazán, Wayo Espinoza Quea, Bernardo Alva and Miguel Canales. Carlos Jacobs was the link between the two groups, as he was already surfing in Lima and he had arrived to Huanchaco in 1967 or 1968 as an outsider that gradually became a member of the local surfing community.

In the winter of 1965, Lima surfer Fernando Arrarte, who worked as a pilot for an agricultural pesticide enterprise and was also a member of Club Waikiki, introduced surfing at the beach resort of Pimentel. The first generation of surfers from this beautiful resort includes Atahualpa Ezcurra, Juancho Yabar-Dávila Cuglievan and Billy Del Castillo. They learned to surf with Fernando Arrarte’s balsawood board that Juancho had bought from Fernando. After Fernando showed them the bylaws of Club Waikiki of Miraflores, the surfers from Pimentel founded their own surfing club: El Club Pacífico Norte.

Pacasmayo developed by itself and separately from Huanchaco and Pimentel. One of the first surfers in Pacasmayo was José Aramburú Zapata—the founder and president of the Pakatnamú Surf Club—and Dr. Walter Koening. Shortly after them they were joined in the lineup by Otto Montoya, the Lopez brothers; Coco, “Gordo” and Choly, Solomon Lau, Kike Plaza, Coty Arana, Gerardo “Yayo” Bulnes, Roberto Luna and the young Jaime Ganoza (later moved to live in Huanchaco). Lucho Quezada was studying and surfing in California before eventually returning to Pacasmayo at the beginning of the ‘70s. Pakatnamú Surf Club was founded in Pacasmayo in January 1971. Quickly they became a regional powerhouse and became the most renowned club with the most competitive success in the area.

There were several surfing championships at the northern beaches of Peru during the ‘70s. The Trujillo surfers began to excel in the early competitions where surfers from Pimentel, Salaverry and Pacasmayo also participated. This prompted the formation of the Liga de Tabla Hawaiana del Norte (Northern Surfing League). Over time the children of the Huanchaco fishermen became interested in the sport and for the first time started to ride waves on a surfboard thanks to their friends from Trujillo. It is here that the first direct descendant of the ancient Yungas fishermen learned to ride a modern board: Pepe Venegas.

Today Peru is recognized as one of the great wave emporiums of the world, but in the mid-‘60s, there were only three beaches where people surfed: Waikiki, Kon Tiki and Punta Rocas. But it didn’t take surfers thirsty for adventure long to see what else was out there. One of the first waves to be discovered was Pico Alto, a gigantic A-frame peak. Located offshore at kilometer 43 of the Southern Pan-American Highway, even today the break challenges the best big-wave riders in the world.

On June 29, 1965, Joaquin Miró Quesada persuaded his friends Miguel Plaza and Francisco Aramburú to attempt what at the time was considered impossible. Tired of being mere spectators, the three surfers grabbed their boards, paddled beyond the breakers at Kon Tiki, towards the open sea and the huge waves that in the distance rose like threatening tsunamis. After 30 minutes of rigorous paddling, the three adventurers reached the legendary Pico Alto. Their eyes could not believe what they were seeing. In front of them huge walls of water rose like mountains before crashing down and exploding, producing a terrifying roar in the process.

Sitting on their boards, the three surfers watched set after set come storming through, before finally deciding to tempt fate. Joaquín was the first to go. He slid down the face at breakneck speed on the back of a six-meter wave. Neither Pancho nor Miguel had ever seen anything like it in their lives. Following their friend’s example, they soon scratched into their own waves and successfully tamed the beast. They spent the entire afternoon trading waves and eventually decided to baptize the giant breaker with the name Pico Alto.

“The point where you catch the waves is quite far from the beach. Perhaps about ten or twenty minutes away from the shore at a normal paddling speed, and that is without taking into consideration the time that the surfer may spend at the very beginning of the paddling, since there is the possibility of getting stuck in the shore-break,” wrote Miguel Plaza in 1967. “Once you have made it out, it is not easy to know where you are exactly, because the wave is located in the middle of a bay surrounded by sand hills and the points of references are not very clear. In addition, it is very easy for the surfer to be carried out by the current. Although the wave always comes from the same direction and breaks fairly evenly varying only in size, the location is something that requires to be mastered with a lot of accuracy, as the breaker seems to be highly variable with a surfer unfamiliar with the place. This may put the surfer in a situation where he can be caught by a wave between sets, if he is not in the right spot.”

When Pico Alto was discovered there was no such thing as a leash surfers who fell off their boards generally had to swim back to shore. Plaza’s chronicle, besides being extremely valuable as it was written by one of the men who inaugurated Pico Alto, offers advice to readers in case of falling off on a giant wave. It is almost a survival manual for big-wave surf riders.

“Pico Alto is no place for the inexperienced,” confirms Plaza.

Since the mid-‘50s, La Herradura was the favorite beach of Lima’s high society. Reading the Baby Schiaffino, one of the best stories of Alfredo Bryce Echenique (Peruvian writer born in Lima), one gets an idea of how important this beach was for the life of Lima’s high society. The fame of La Herradura, a natural paradise for surfing, goes back to the early 20th century, when the first swimmers from Chorrillos (a district in the city of Lima) made use of the powerful waves by body surfing or riding surf mats to shore.

The soft sand of La Herradura is an ideal place to spend a summer day. However, when a big swell is running La Herradura can become a fearsome beach with double overhead waves that can ravage the shoreline. In those early days vacationers would perceive a curious phenomenon that took place along the hill that surrounded the bay. From the top of the hill they could see huge waves, rolling along for four hundred yards, crashing against the rocks and the caves of the cliffs, creating a thrilling spectacle. Undoubtedly, the first surfers saw these waves in all their glory, but they all agree that no one even remotely thought about surfing such mountains. The huge boards they had at the time practically guaranteed that they would end up buried in some sinister, rocky cavern.

It was not until the ‘60s that Peruvian surfers started thinking about the possibility of challenging the waves of La Herradura. In an article written in 1962 by Joaquin Miró Quesada, our unforgettable Shigi, he describes how Peruvian surfers fantasized about riding La Herradura on strong days, but the idea of ending up smashed against the rocks always made them abandon their fantasies.

In the winter of 1965, the new world champion Felipe Pomar and a select group of surfers, among them Fernando Arrarte, Francisco and Carlos Aramburú, and Manolo Mendizábal, set out to make history. When the ocean showed the first signs of a big swell and the coast appeared covered with foam, the five friends headed south. They arrived at the bay equipped with their best boards. They were ecstatic at the sight of sets neatly rolling into the bay. After waiting for the ocean to present them with an opportunity to paddle out, they cut across the roaring closeout on the shore and headed far out towards the distant break line.

As they progressed they were hypnotized by the giant barrels expelling violent plumes of water. Adrenalin coursed through their veins. Eventually making it outside, they sat huddled, waiting for the next fateful set to hit the lineup. Felipe Pomar was the first one to go. Soon, the five friends were surfing waves along the bay, howling with pleasure. News spread quickly among surfers and on the next swell on December 31, Joaquín Miró Quesada, Miguel Plaza, Francisco Aramburú, José Carlos Godoy and Sergio Barreda enthusiastically surfed the wonderful waves of La Herradura from dawn to dusk.

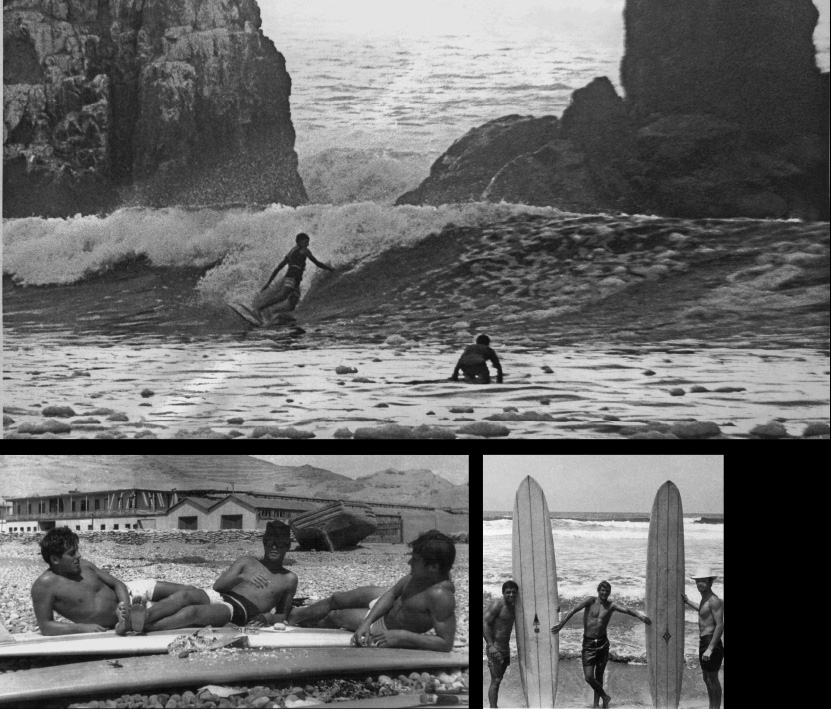

In 1961, another legendary wave would join the handful of beaches where Peruvians surfed. It was spotted for the first time from the Pan-American Highway in the late summer of 1961 when Mota Navarro and a group of friends were coming back to Lima from Mota’s estate in Chincha. In the car with them was Californian John Severson, a friend of both these surfers and publisher of Surfer Magazine. He was the one who first spotted the waves crashing against the rocks. Intuition led him to suspect that good waves were close by. In Peru filming a surfing documentary, Severson and his friends immediately got off the highway and headed to Cerro Azul.

Accompanying Mota Navarro and John Severson was a handful of notable surfers including, Raúl Risso, “Pocho” Caballero, Carlos Aramburú, Joaquín Miró Quesada and Felipe Pomar. When the seven surfers finally got there they were underwhelmed. They watched and wait, hoping that a change of tides or a strong wind would bring some surf, but by nightfall they all returned to Mota’s estate to sleep. The plan was to try again the next morning.

Getting to Cerro Azul at dawn it appeared as if a miracle had occurred. One and a half meter waves were neatly rolling into the bay, feathering along in perfect symmetry for over one hundred yards until finally reaching a pier. The boys couldn’t get in the water quick enough. The waves surfed, the maneuvers performed, the barrels that they got themselves into, and, especially, the movie that Severson made of that memorable session, established Cerro Azul as one of the greatest discoveries of the decades.

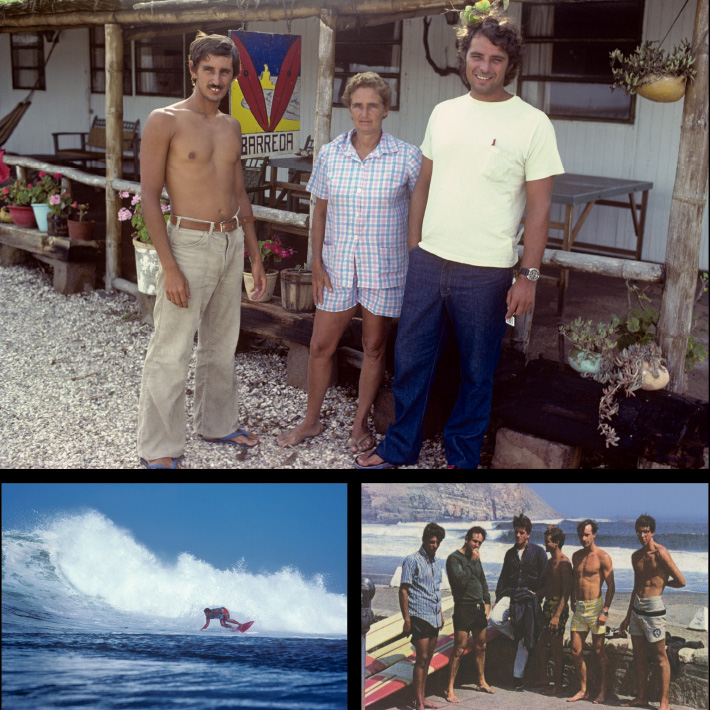

To this day Cerro Azul is the favorite beach of hundreds of surfers, some as famous as Gordo and Flaco Barreda. The relationship between the beach at Cerro Azul and the Barreda family is widely known in Peru. In 1962 they built the first beach house in the beautiful bay and Mrs. Sonia, with her children Sergio and Carlos, became the first surfers to permanently enjoy one of the most perfect waves in the world. The Barreda brothers studied at Champagnat School, and whenever the surf was up, Joaquín Miró Quesada and Miguel Plaza would pick them up at school to surf.

One day, the director of Champagnat School urgently called Mrs. Barreda, to ask her what her children were going to do with their life, surf or study. With the utmost elegance, Mrs. Sonia replied: “Sergio, Carlos, grab your things, we are going to the beach.”

The Barreda brothers finished school without major problems and would soon become two of the most important surfers in Peru. In an article written in 1967 by Carlos “El Flaco” Barreda, he writes, “It seems that Cerro Azul was just created for surfers. It is the perfect place. It can give surfers everything that they are looking for: waves, sunsets. It is a closed site, a beautiful and friendly beach. It is isolated from the sea by black and pointed rocks that turn white with foam when a wave breaks. In the small bay the water is as calm as a pond: only a perfect wave formation stands out. They all follow a set order. They start and end in a set place. They are created at a steady speed. They are perfect. They are not big. They’re the size that I like: an average of one and a half meter high. It’s the wave that I can handle instead of being carried away by it. It’s where I can perform the best I can, as the wave already does everything that you can ask a wave to do. The evening sun colors Cerro Azul golden. A gentle beach breeze make the waves look like blond hair when the waves break. The water is fresh and it contrasts with the salty sunny sting on my back. I could spend my lifetime surfing these waves. It is never monotonous to me. It is all I can wish for.”

Today, sitting in his office in Miraflores, Dr. Carlos Barreda lovingly speaks of his cherished Cerro Azul: “I remember, for example, an entire week in May, 1966. Joaquín Miró Quesada, Ivo Hanza and I at Cerro Azul, with perfect waves day and night: everything for just the three of us. I do not think that this happens elsewhere in the world, where you often you see dozens of surfers fighting until death for a miserable wave. We are lucky that we are better off than they.”

José Orihuela, and engineer by trade, first discovered the wave at Bermejo. In March 1964, Mr. Orihuela was invited to spend a few days at the Paramonga Estate. He took his children with him, three of whom were surfing fans. Upon arrival the Orihuela brothers immediately realized the quality of the Bermejo waves and with a group of friends became the first to surf the spot.

Richard Fernandini recounts that when he learned about the existence of the break he immediately grabbed his board and got on the road. When he finally got to Bermejo he found a fascinating spectacle. The hills were colored red and blue. The water was crystalline and the waves broke perfectly with a headwind forming an extraordinary barrel. Along with Joaquin Miró Quesada and Dennis Gonzalez, he spent days in Bermejo, surfing wave after wave. Even with its colder water temperature the boys surfed on—this was, after all, before wetsuits had been invented.

Bermejo quickly became a well-known spot, even attracting foreign surfers. With the discovery of Bermejo, the exploration phase of the northern beaches got underway with gusto. Soon Peruvian surfers would marvel at spots such as Chicama, Cabo Blanco and Mancora.

The surfers who lived in the areas around La Punta and Callao were hugely influential. Papo Guerra has noted that over time the surfers of La Punta were finding the right places to practice their favorite sport, and thus the names of important beaches such as Las Tres Marías started showing up on the maps. Whenever they had time to spare, the surfers from La Punta traveled to Barranca and camped at one of its secret beaches. The tradition of visiting these beaches became so established that in 1978 they started organizing championships in the area.

In 1967 a surf expedition embarked on a journey that would culminate with the discovery of one of the longest waves in the world. As in the case of Kon Tiki, the discovery of Chicama was made possible by information provided by a Hawaiian. A man by the name of Chuck Shipman was flying over the bay when saw an incredible formation of waves travelling hundreds of yards in unparalleled perfection.

With this information, Carlos Barreda, Ivo Hanza, Pancho Garruéz, Bertrand Tazé-Bernard, Carlos Aramburú and Chino Malpartida piled into a rugged Citroneta and trusty Volkswagen Beetle and headed north. When they arrived at Puerto Chicama (nowadays known as Malabrigo) they verified Shipman’s description. The surf was small, but that did not prevent them from appreciating the perfection of the waves rolling into the bay.

Thanks to the hospitality of some fishermen, the group spent the night hoping the next day would bring more swell. In the morning the young surfers walked along the shore looking to discover the source of all those waves. Finding a lineup at the top of the point, they chose the name “Cape” in honor of the famous South African surf break Cape Saint Francis. They paddled out immediately, and as Flaco Barreda, a small-wave specialist, remembers, they had the best surf session of their lives. The waves moved at high speed and offered up numerous tube sections.

When a set of big waves rolled into the bay the Peruvian surfers frantically paddled further out to meet it. They scrambled to reach the second section, now known as The Point. A small film camera recorded and immortalized the session. They celebrated the spectacular discovery with a showing of the film at Club Waikiki and ever since Chicama has been one of the favorite spots of Peruvian surfers. The quality of the wave challenged the surfers to improve their style. However, the waves at Chicama need a decent sized swell to come to life and getting it good proved to be an exercise in patience. Chicama’s fame caused thousands of surfers to come to Peru in pursuit of its waves. In fact, when the most prestigious surfing magazines publish their rankings of the best beaches of the world, Chicama always makes the list. When one sees how perfectly these waves break it’s easy to understand how and why the art of surfing originated not far from there.

One of the most important Peruvian surfers in the early ‘60s was Joaquín Miró Quesada, who became a major player in the surf scene when he was crowned Peruvian surfing champion in 1963 and 1964. Joaquin is remembered by contemporary surfers as one of the driving forces of the new era of Peruvian surfing. If there was ever a man who devoted his entire life to worshipping surfing it was Joaquín. He was an endless source of inspiration for the surfers in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

“Shigi,” as he was called, took incredible photographs, wrote interesting articles and encouraged his friends to start searching for new waves. When he was 22 years old, he traveled to Hawaii with Miguel Plaza and they surfed at Sunset Beach, Waimea Bay, Makaha, Yokohama Bay and other surf breaks. His life ended tragically early when he was surfing at Pipeline, wiped out and was thrown violently against the reef.

1962 Peruvian Big Wave Championship – 1st Place

1962 Club Waikiki’s World Championship – 2nd Place

1962 La Herradura – Club Waikiki Paddleboard Event of Club Waikiki’s World Championship – 1st Place

1963 Peruvian Big Wave Championship – 2nd Place

1963 Club Waikiki International Championship – 2nd Place

1963 La Herradura – Club Waikiki International Paddleboard race – 2nd Place

1965 Peruvian Big Wave Championship – 1st Place

1965 First ISF World Championship – 1st Place

1965 La Herradura – Club Waikiki Paddleboard race during the First ISF World Championship – 2nd Place

1965 Highest Peruvian Sportsmanship Award in the degree of Commander with gold insignia

1965 Duke Kahanamoku Invitational (Hawaii) – 3rd Place

1965 Surfer Magazine (according to readers’ survey) – Ranked: 9th

1966 Peruvian Big Wave Championship – 1st Place

1966 Club Waikiki International Championship – 1st Place

1966 La Herradura – Club Waikiki International Paddleboard race – 2nd Place

1966 Duke Kahanamoku Invitational (Hawaii) – 4th Place

1966 Duke Kahanamoku Sportsmanship Award (Hawaii)

1966 Makaha International Championship (Hawaii) – 5th Place

1966 European Paddleboard Championships (France) – 1st Place

1966 Surfing Magazine (Hall of Fame) – 1st Place (PERU) and 5th Place (International Big Wave)

1967 Club Waikiki International Championship – 2nd Place

1967 La Herradura - Club Waikiki International Paddleboard Race – 1st Place

1967 Haleiwa International (Hawaii) – 1st Place

1968 Club Waikiki International Championship – 4th Place

1968 La Herradura – Club Waikiki International Paddleboard race – 1st Place

1968 Duke Kahanamoku Invitational (Hawaii) – 4th Place

1969 La Herradura – Club Waikiki International Paddleboard race – 1st Place

1969 Duke Kahanamoku Invitational (Hawaii) – 7th Place

1969 The Outrigger Canoe Club Surfing Championship (Hawaii) – 1st Place

1970 Smirnoff International (Hawaii) – 2nd Place

1970 Makaha International (Hawaii) – 2nd Place

1987 President of the Peruvian National Surfing Federation – FEPTA

1991 Sunset Beach – Waimea Bay Masters Paddleboard race (Hawaii) – 1st Place

1992 Sunset Beach – Waimea Bay Masters Paddleboard race (Hawaii) – 1st Place

1993 The Outrigger Canoe Club Masters Paddleboard race (Hawaii) – 1st Place

1993 Sunset Beach – Waimea Bay Masters Paddleboard race (Hawaii) – 2nd Place

1994 Sunset Beach – Waimea Bay Grand Masters Paddleboard race (Hawaii) – 1st Place

2004 Hennessey’s Grand Masters Paddleboard Championships (Hawaii) – 1st Place

2005 Hennessey’s Grand Masters Paddleboard Championships (Hawaii) – 1st Place

2007 Ambassador of the world for the District of Huanchaco – La Libertad Region

2013 La Herradura – Club Waikiki Paddleboard race participating for the Waves of Peru

2013 Lifelong Guardian and Ambassador of the Huanchaco World Surfing Reserve

After participating in the 1966 World Surfing Championship in San Diego, Sergio Barreda Costa seized on the opportunity to make every surfer’s dream come true and visited Hawaii. Gordo had just turned 15 and was about to experience one of the most exciting adventures of his life. In those days, Sunset Beach was the gold standard for big waves and only a few people were actually brave enough to attempt to ride it. Gordo devoted himself to the wave, and was also able to experience memorable sessions at Pipeline and Rocky Point. Within days Sergio felt his style had improved considerably, not only since he had been surfing epic waves, but because he also had the chance to appreciate and learn from the Hawaiian surfers.

The Peruvian champion in 1968, 1969 and 1970 (he won his fourth title in 1974). In ‘68, when Gordo participated in the World Championship in Puerto Rico, the “Shortboard Revolution” was in full swing and boards were dramatically shrinking in size. In ‘69, Gordo was invited to participate in the Duke Kahanamoku Surfing Classic Tournament in Hawaii. The invited surfers had been selected based on the results of a survey, and Gordo would ride alongside 23 of the best surfers in the world.

At the Duke Kahanamoku Surfing Classic, Gordo’s performance was greatly admired. At first, Hawaiian newspapers expressed their surprise when they found out there was an 18-year-old boy surfing the powerful waves of Sunset Beach, but as various surfers were being eliminated, Gordo climbed positions and managed to reach the final.

When the final ended Gordo was in eighth place, however the next day his picture was in all the papers. While the judges did not consider him the best, he’d captured the public’s imagination.

“I fulfilled my obligation to represent my country well; now I will give it my very best,” he said afterwards.

CHAPTER ONE: THE FISHERMEN SURFERS

CHAPTER TWO: NAVIGATION IN ANCIENT PERU

CHAPTER THREE: A PLAUSIBLE PERU-POLYNESIA CONNECTION

CHAPTER FOUR: THE HAWAIIAN TRADITION

CHAPTER FIVE: CARLOS DOGNY LARCO AND THE CLUB WAIKIKI (1938 - 1949)

CHAPTER SIX: THE FIRST YEARS WERE INSTITUTIONAL (1950 - 1959)

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE AMAZING DECADE (1960 - 1969)

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE RISE OF THE BROTHERS OF THE SEA (1970 - 1979)

CHAPTER NINE: EVOLVE WITH YOUR SPORT (1980 - 1989)

CHAPTER TEN: THE BEGINNING OF MODERN HISTORY (1990 - 1999)

CHAPTER ELEVEN: PERU: TOP LATIN AMERICAN SURFING POWER (2000 - 2009)