Several milestones during the ‘80s spread surfing to a broader audience. Surfboard manufacturers became much more proficient at their craft, materials became more available, and shapers started popping up all over the place. Also, the used board market gained in popularity allowing beginners to buy boards at even more affordable prices. Leashes, wetsuits, waxes and surf clothing turned into a legitimate industry. Worldwide, surfing obtained its own identity, becoming a genuine lifestyle. Peruvian surfers embraced it all and fell in love all over again.

In the early 1980s most people were still riding twin-fins—a board with two fins. But in the early ‘80s Australian surfboard designer devised what he called the “Thruster.” Built with three equally sized fins. The new invention proved to be more responsive and hold a tighter line in critical parts of the wave. It was the state-of-the-art, high-performance innovation that changed the sport forever. It is still the preferred design for the majority of the surfboards manufactured around the world today.

Cheyne Horan’s floater became one of the most practiced of the new maneuvers that Thrusters allowed. Eventually they would all surfers to take to the sky with all new electrifying aerial moves. A number of these innovative maneuvers were done for the first time in small conditions, to then be carried out in big waves as well.

The surf breaks discovered in previous years like Máncora, Cabo Blanco, Chicama, Bermejo, and the new ones discovered in the ‘80s, such as Conchán, El Huaico, Pepinos, San Gallán, Puerto Caballas and Bayóvar, became mandatory destinations for Peruvian surfers keen on honing their skills. They often hit the road in caravans heading for these now legendary waves. Peruvian surf magazines like Tabla and Tablista allowed the sport to reach new segments of the Peruvian society. Surfing was now appreciated as a healthy, fun and exciting sport.

The Carlos Dogny Invitational was one of the premier, professional event in Peru in this era. It was so well organized that in its second and third years it attracted international talent such as Buttons Kaluhiokalani, Jackie Dunn, Mark Liddell, Mickey Nielsen, Randy Rarick, Rory Russell, Mark Foo, Ronnie Burns, Michael Willis, and other exceptional talent. Hawaii’s George Downing served as the judge of the event.

The contest was held from 1980 through 1982 at Punta Rocas. In its first incarnation in ’80 only Peruvians surfers participated. Miguel “Mico” Tudela Gubbins was in charge of the organization, assisted by Carlos Dogny Larco. It was won by Mario Chocano (prize purse of $1,000). In 1981 Buttons Kaluhiokalani won (prize purse of $5,000) and in 1982 the winner was Ronnie Burns (prize purse of $10,000). Raúl “Patero” Calle was the best Peruvian surfer; he was the runner-up in the second and third edition.

In 1981 Simon Anderson, an Australian shaper from Narrabeen, New South Wales, participated in the Rip Curl Pro Bells Beach and in the Coke Classic Surfabout in Narrabeen, winning both events in a row. Months later he also won the Pipeline Masters. The display of speed and radical turns was enough to prove that his three-finned “Thruster” board design worked. His work marked the end of the reign of Mark Richards’ twin-fin, which was the defacto board design of the ‘70s. Richards was the most dominant surfer during the late ‘70s, winning the world title four consecutive years in a row from 1979 through 1982. Thanks to his impressive victories and design revolution, in 1981 Anderson was declared the “Surfer of the year” by Surfing magazine.

Anderson’s contribution swept through the surf world like wildfire and almost overnight the demand of his boards exploded. This shaping frenzy went so far that boards with seven fins were created, but ultimately Anderson’s Thruster was adopted due to its high performance. The tri-fin design allowed the surfer the necessary drive, speed and control. Peruvian shapers like “Wayo” Whilar, “Niko” Wilhelmi, Ricardo Kauffman, Pedro Vásquez, Rodolfo Klima, César Aspíllaga, Rodrigo Gamarra, Milton Whilar, Alejandro Ortiz, “Gordo” Barreda and many others introduced their own tri-fin designs to the Peruvian market and were well received by the national surfers.

Gordo Barreda sold leashes in his surf shop located in Miraflores. These relics were used for many years by the Peruvian surfers. Made of multiple thin rubbers wrapped by rope-like material and an ankle leather strap, they were resistant, affordable and did the job. However, at the beginning of the ‘80s they were replaced by modern, more functional leashes with lesser spring and an easy-to-release velcro cushioned ankle strap. One of the most celebrated surfers at La Herradura, Luis “Chato” Rojas, saw an opportunity in the leash business and become an entrepreneur. Chato manufactured his own leashes, matching the quality of the imported ones.

One of the main characteristic of the ‘80s was the big impact of the surfing fashion amongst mainstream Peruvian youth. Peruvians fell in love with American and Aussies surf brands. Op tee shirts, Offshore trunks, and a big surf clothing assortment of new brands like Quiksilver, Stussy and Gotcha was suddenly the main preference by Peruvians, not only in the beach communities but in the Peruvian highlands as well.

Before the ‘80s surf fashion had not been so widely accepted, but the sport was gaining recognition beyond its boundaries. More surfers and people paid attention to their style since it was considered more interesting than regular clothing. Besides being surfers, many of them were much attached to nature and keen to conserve it. They were aware of the environmental threats and they loved adventure—characteristics that fit very well into the modernity of the ‘80s. Thanks to these developments, surfers were able to make a living through activities associated with their surfing passion. It became clear that being a surfer was not at odds with being a businessman or businesswomen.

In Lima a mainstream radio station known as Double Nine started to air “The Ocean Report” to help provide surfers with more real-time wave-related news. The surfcast was the brainchild of Javier “Cavi” Raffo. Every morning he would go down to Costa Verde to check out the waves and then broadcast the report. The service was later carried out by Gordo Barreda, Magoo De la Rosa, Roberto Meza, and Rodrigo Gamarra. Currently, Chalo Espejo is handling the reporting and forecasting responsibilities.

Lima surfers listen to “The Ocean Report” because its valuable information provides the tools to gage the quality of the wave, the height of the waves, the direction of the swell, the wind conditions and the tides. When Double Nine is announcing that La Pampilla is breaking four feet, glassy and tubular, who’s not going to drop everything and go surf? Thanks to this report, surfers could better organize their daily agenda to make room for surfing. Many people listen to Double Nine because of its progressive rock, but surfers, real surfers, never miss “The Ocean Report.”

“It was January 1981 and Juani Bazo and I went to check out the waves at Punta Hermosa,” says Ricardo “Cholo” Bouroncle about the discovering of Playa Negra. “It was flat and while we were watching the non-existing waves. ‘Papa’ Fernandini showed up in his brandnew SUV Jeep Cherokee. We picked up the smaller surfboards and went down south to test Fernandini’s SUV and see if we could find something to surf. We went off-road several times, driving close to the sea, looking for waves, and saw nothing. When we were approaching Puerto Fiel [80 miles south of Lima] we noticed swell lines on the ocean that took us by surprise, considering that it had been flat since we left Punta Hermosa. At the time, I was not familiar with swell directions and because this headland is exposed to the north swell, a very typical swell during January, it allowed waves to break here during the Peruvian summer time. Upon arrival, we went to the top of the hill that dominates today’s beautiful beach community, yet at that time there was nothing there. As we reached the summit of the hill, we watched, marveled a set of perfect waves coming in. The mild off shore wind from the south was gently hitting the walls of the waves. Just by serendipity we found one of the must tubular waves in Peru, located close to Lima.”

In 1982 a surf magazine called Tabla (“board” in Spanish) was born. Created by surfer Harry Yearwood and directed by Jorge Montoya, the now legendary first issue of this magazine included a well-written article warning Peruvian surfers about a serious threat to La Herradura—the Chorrillos Council was planning to build a highway. The report was a touchstone for Peruvian surfers’ attitudes on waves and their coastal environment. They defended their playground and pushed for legislations protecting the coast. The first issue of this magazine had only 16 pages and literally disappeared from the newsstands as soon as it was released. The demand illustrated the huge interest of the public to learn about surfing and other aspects related to the sport. Montoya never got on a surfboard in his life, but he was a smart entrepreneur. Besides the magazine, he organized several surf contests, opened a surf shop called Tabla Surf Shop and managed to launch a weekly surf-themed TV show that aired every Saturday on Channel UHF-27.

In Tabla issue No. 6, Carlos Echecopar Mongilardi narrated a wonderful story. He started by telling the readers that during the ‘70s he was a motocross rider, and because of that he had the chance to watch a wave in a remote beach off from Palpa, Ica [250 miles south from Lima]. In Punta Caballas, 60 miles west from Palpa, there are three beaches with waves. The first one has a nice shaped wave, the second one has a mediocre wave, and the third one has a long tubular wave.

During the long weekend of Easter in 1980, Echecopar decided to come back to this place, escaping from other overcrowded beaches closer to Lima. This time he did not bring his off-road bike with him, but instead brought camping gear, including Peruvian Pisco and his surfboard. He headed toward Palpa on the Pan-Am Highway and once he saw the beach he turned west. Making his way through the merciless Ica desert, there were no road signs whatsoever. In the end it took Echecopar four hours to get to the beach.

The effort proved worth it. Echecopar and a friend surfed the perfect waves alone from the crack of dawn until noon. The morning offshore wind made the waves beautiful. They were the only two surfers in the area. The only other people out there were the local fishermen. The waves, the wind, the gorgeous marine vista of this hidden fishermen’s cove, they could hardly believe their good fortune. It made for a marvelous weekend filled with harmony and nature.

“We were so far from Lima and yet so close to ourselves” wrote Echecopar.

The first surfers to explore the deserted area of Bayóvar in Northern Peru was the crew from Pimentel. The story goes that Chino Zevallos had gone to Bayóvar with his uncles since he was 10 years old (during the early ‘70s). His uncles were fishing aficionados and it is well known that Bayóvar is a primo beach for such activity. When Zevallos reached the age of 16 he was already a good surfer, and his uncle “Topo Gigio” Aurich told him that he had seen waves in Bayóvar and that it would be a good idea for him to go and check them out. An enthusiastic Chino told his friends Cañaña Monsalve and Alvaro Rey about the waves. In 1980 the three friends went to Bayóvar, leaving from Pimentel in an SUV. It was a smooth 120-mile trip on a beach called “Playa Sin Fin” (Endless Beach). It had to be done during low tide otherwise the water was too high to drive. Along the way they discovered Punta Tur. The Pimentel surfers were the first to ride this amazing wave, which can reach triple overhead on a good day.

During the summers of ’82 and ‘83, Northern Peru was left a wasteland by the El Niño weather pattern. Torrential rains formed gorges as deep as 130 feet, erasing any road to Bayóvar and cutting off all access to this beach from the Pan-American Highway. In ’84 a group of Lima surfers led by Rodolfo “Gorilón” Bejarano went to Bayóvar. He had visited Bayóvar during the El Niño in ’82, when he had used the road from the north side of the town, where the oil pipeline that comes from the jungle reaches the shore of Bayóvar to be transported by oil tanks.

On his return visit Bejarano and friends abandoned the Pan-American Highway, using whatever roads were left after the rains. The surf expedition suffered from day one. Flat tires and constantly being stuck in the mud took its toll on the resilient surfers and several of them voiced their discontent and wanted to turn back. Bejarano was able to convince them by recounting his own experience with this amazing wave. After three days of misery they finally reached Punta Tur.

After this experience Bejarano organized more surf trips to Bayóvar. On one of his trips he invited some staff members of Tablista (another Peruvian surf magazine), and in its issue No. 7 (1988), Tablista published a spectacular article about this surfer’s paradise located on the Illescas peninsula. The article of the surf adventure was written by Javier Huarcaya Pro. Javier García Burgos was the photographer. The Huarcaya brothers (Javier and Fernando), Mario Chocano and Rodolfo Bejarano himself were documented in the photos in the article. This set off an ardent desire within Peruvian surfers to visit Bayóvar.

Bayóvar is not an easy place to ride. The environment is harsh and the waves are not for beginners. It is necessary to bring everything, including water, food and fuel. In addition the surfers must have the guts to ride such challenging waves. It is worthwhile though and camping there is quite pleasant. Being in Bayóvar is like going back in time, when one could admire the wild flora and fauna. It is not unusual to see foxes at night or watch condors flying thru the gorges at dawn. Hummingbirds, penguins, goats or even wild donkeys are part of its fauna, making Bayóvar a uniquely beautiful place.

Gorgeous pictures of Nonura shot by Steve Wagner were published years later in Tablista (issue no. 14, 1992). This time the travelers arrived via a J/24 sailboat sailed over from Miami, Florida. Besides Wagner, the crew was comprised by Enzo Rovegno, Aldo Ciccia, Dicky Pérez and Mario Chocano. The following year another group of surfers organized an expedition to Bayóvar. This expedition was put together by Roberto Meza, Carlos “Perro” Ochoa and Javier “Javo” Campodónico, the latter a surfer from Pimentel. With the information provided by Enzo Rovegno and Mario Chocano, they traveled to a port on the Sechura Bay called Puerto Rico, where they rented a boat from the fishermen and headed to Nonura Point. There they surfed for the next five days. During their time there they discovered a new point which they named Mal Nombre; a super-fast left barrel. It was a memorable experience because two of them, Perro Ochoa and Javo Campodónico, were celebrating their college graduation from University of Lima Law School with this trip and they scored amazing waves as a reward for their academic efforts.

1983 was a disastrous year for the local Lima surfers. The sitting mayor of Chorrillos proposed a series of absurd measurements that included the demolition of the wall of Regatas Club, a private club founded in 1875, so all beachgoers could have access to the club facilities. When the initiative did not take off, the mayor redirected his frantic attacks to La Herradura. According to the mayor, Chorrillos would benefit from the construction of a highway linking the beaches of La Herradura in the north with La Chira in the south. Dismissing the surfers’ vocal rejections of the plan, the mayor moved forward with his project and consequently La Herradura, one of the best waves of in the world, was destroyed.

La Herradura had been a heavenly beach town. Where Peruvian surfers gathered together to surf one of the biggest and most aggressive waves on Peru’s coastline. Neither the tradition of the beach, a favorite getaway for Lima residents since the beginning of the 20th Century, nor the protest of surfers and beachgoers stopped the mayor’s project. To make room for the new proposed highway it was necessary to dynamite part of the headland, essentially destroying the pristine marine environment. Rocks fell down from the hills and piled up on the shore where they were dragged out to sea by the waves and current, forever replacing the sandy seabed of La Herradura. All of this construction had a negative impact on the waves at La Herradura. They still break today, but they are of a considerably lower quality since the failed highway construction.

César Aspíllaga, one of the surf masters of La Herradura, wrote his thoughts about this project in a moving article published in Tablista at the beginning of the ‘90s.

“Since they attempted, and failed, to build a highway from La Herradura to La Chira, destroying the unique nature of this place, the wave of La Herradura has changed a lot, and now it is only surfable when huge swells come in,” wrote Aspíllaga. “Out of a six-wave set, only one wave is well formed. Before, this beach only needed a medium swell to start pumping excellent waves; five out of six waves per set were perfect. This unfinished highway, besides damaging one of the best waves worldwide, because so it was, also has affected the beachgoers that used to come to La Herradura, a wide sandy beach, now a narrow beach full of rocks. The spectators that want to have a better look at the wave need to go on the highway, where they very often get robbed. The robbers are most likely from La Chira, because after committing their felonies they have been seen disappearing behind the headland in that direction. A lot of money has been invested in this project, and now it is abandoned. La Herradura was one of the best waves in the world, which only the surfers who were lucky enough to ride it would know, before it was destroyed for nothing.”

This sad event serves as a constant reminder of how fragile the marine ecosystems is, especially when people abuse it. It is also a reminder of how important it is to preserve and protect the limited marine resources left. The destruction of La Herradura as a beach, a surf break and a place of recreation is a deep wound in the collective memory of the Peruvian surfers and a hard lesson to keep in mind for future generations.

While living in Hawaii in 1983, Raúl “Patero” Calle became one of the founders of the surf brand Olas. Along with a small group of surf friends, he hired the renowned artist Dean Edwards, the shaper and designer of Natural Progression Surfboards in Santa Monica, California, to create Olas first logo. Edwards did a neat job and the logo was well received. A couple of years later Olas introduced a new surf clothing line to the Maui market designed by Hawaiian artist Richard Fields. The founder of Tabla magazine, Harry Yearwood, was in charge of the merchandising and distribution of this clothing line in California, USA. In Peru the brand began to sponsor a new generation of young surfers. They traveled around the world using Olas equipment, exposing the brand in the world’s most famous surf breaks, and in the ‘90s the brand went global, opening shops in Maui, Bali, Australia and Japan.

Olas sealed a genuine alliance with Roberto Meza, owner and director of surfing school Olas Perú, and with Jorge Barrios, owner and operator of Olas Navigator in Indonesia.

At the beginning of the 21st Century, Brazilian Reynaldo Zapp modified Olas’ logo under the supervision of Raúl Calle and few friends, among them Renzo Ciccia Peirobon who was the actual owner of the brand and a big-wave rider. The design of the letter O was done in a more stylized way, wrapping the word Olas, which kept its original typography.

“Our idea was to create a new corporate identity to become an official Peruvian surf brand,” said Raúl Calle.

In 1976, four years later after Eduardo Arena’s resignation, members of the ISF gathered in Hawaii and decided to change the name of their organization to the International Surfing Association (ISA). In 1978, under the direction of South African Basil Lomberg, the surfing entity started to organize international surfing contests. The ISA World Championship was held every other year from 1978 until 2002.

Peru did not participate in the first three ISA contests held in South Africa (1978), France (1980) and Australia (1982). These contests were nowhere close to the magnificence of those celebrated under Arena’s presidency. Peru first participated in the ISA World Surfing Amateur Championships in 1984 in Huntington Beach, California. The previous year the Comisión Nacional de Tabla (CONTA, National Surf Commission), led by José “Pepe” Whilar, had decided to join the ISA.

On a hot, sunny Saturday in February 1984, a group of friends had the good fortune of stumbling upon a new, never-before-surfed wave. “That Saturday we were hanging out on the beach front of Cerro Azul, watching the ocean, when after a while Carlos “Flaco” Barreda joined the group and told us that he has seen a nice wave in the river mouth of the Cañete River. That day Cerro Azul was not pumping at all and it was not hard for Flaco to convince us to go with him toward the river mouth,” recalls Roberto Meza, recounting the discovery of Pepinos.

“In the group were Luiggi De Marzo, César Tapia and my brother Ricardo. Once we got there we noticed that the better wave was on the other side of the river mouth, and we went there by car. We reached a cliff where we found a farm with Pepinos (a South American melon-like fruit), and we parked the car there to unload the boards and headed towards the wave. The road to the river mouth was full of Pepino crops making it impossible for us to see the wave. Once we reached the edge of the river we were pleasantly surprised by a shoulder high left wave breaking nicely before our eyes. We surfed these spectacular waves for more than three hours and since then we called that surf spot Pepinos. We came back the next day for more surfing and since then we have visited Pepinos many times. Pepinos is a left wave that resembles some of the sections of Señoritas, and we can enjoy it when the waves are small. We have also surfed this break with big swells when the waves were reaching ten feet high.”

In 1982 Rocío Larrañaga Leonhardt was traveling by plane from Lima to Arequipa and as she was admiring the view of the Pacific Ocean she saw a set of well-organized waves breaking off an unknown island off the Paracas Peninsula. Once she got back to Lima, Larrañaga enthusiastically told her fiancé Luiggi Boza, about her discovery. A couple of years later a co-worker of Luiggi’s, Lucho Alcázar, who was an accomplished spear fisherman on the Paracas Peninsula, told the young married couple that off Independencia Island he had seen some nice waves that were appropriated for surfing. The news motivated them to organize a trip to explore.

On a nice summer night, Rocío, Luiggi and his brother, Andrés, gathered in the family home. Andrés explained that he had recently been fishing off San Gallán (another island off the Paracas Peninsula) with his friend Enrique Dibós. He had shot several pictures of the waves that were breaking there while they were fishing. Immediately they started to study the images, and while they seemed to be rather small they had a good shape.

“That is the island that I saw from the airplane, that one located in front of the peninsula,” declared Rocío excitedly while pointing to a map.

Unanimously the decision was made, instead of going to Isla Independencia the would head to Isla San Gallán. The couple’s friend, Herbert Berger, was a pilot and they asked him to keep an eye on the waves when he was flying over San Gallán. Shortly after Berger confirmed of the existence of nice waves off San Gallán. They organized a trip to Paracas and in October 1984 headed to Pisco, a port south of Lima and close to the peninsula. Puerto San Andres was the first stop before San Gallán. There they hired a boat and a crew. The next day at dawn they boarded the Bismarck. The surfers onboard included Carlos Echecopar and Charo Vásquez, Peter Mongilardi and Ana María Valdéz, and Luiggi Boza and Rocío Larrañaga. Along with their boards they packed all necessary camping items with the intention of spending the night on the island.

“Seashell-like waves are breaking in Punta Brava,” explained one of the fishermen onboard.

Like that they set a course for Punta Brava. When the boat reached the point there were no waves to be seen. They kept heading north towards a deserted beach of Isla San Gallán, located across five islets, one of them full of sea lions. The fishermen refused to disembark due to superstitious beliefs and the couples spent the night on a very uncomfortable, windy, rocky beach that was littered with remains of sea lions and other creatures.

The next day after breakfast the Bismarck came to pick them up. They headed back to Punta Brava hoping to find waves and were not disappointed. It was pumping! Luiggi, Carlos, Peter and Rocío got their wetsuits on while Charo and Ana María were in charge of snapping the pictures.

“It was a wonderful thing for us, because it confirmed a new break for surfing. Everybody felt great satisfaction while we were surfing there, we could hardly believe it” remembered Rocio in for Tablista issue No. 14.

After a long surf session they went to their camping site where they devoured a hearty dinner. The comments and conversations about their amazing discovery died off only as they went to sleep. A new day dawned, and again the surfers headed to Punta Brava. More waves, more fun, and more anecdotes to share with friends. Punta Brava off of the island of San Gallán was quickly recognized as one of the most beautiful right waves in Peru.

My name is Pedro Vásquez Huarcaya; I became a surfboard shaper in 1978. It was the time of the military dictatorship government and there was a scarcity of blanks. Clark Foam factory in Peru was closing their facilities and they were selling its remaining blanks at the beginning of the eighties. Sometimes I was forced to buy whatever the foam market had to offered, even if it was a 7´10” x 3 ½ oversized imported blank, that was then used to hand shape a small board of 5’2” x 2.2”. Keeping in mind that board making computer aided machines were not yet available, I can tell you that shaping was neither an easy nor efficient task. One day in 1982 I made some tests with expanded polystyrene (EPS) known also as styrofoam, evaluating the possibility of the use of this material with surfboards. I was the worldwide pioneer, at least 20 years ahead of time, in successfully using EPS and epoxy resin. Although it is true that similar developments had taken place in other places of the world since 1949, like New Zealand, Australia, California and Florida in the U.S., South Africa, Japan and Europe, I was not aware of such developments when I started with the EPS blanks. I can tell you one thing, none of the companies from those other countries had neither the commercial success nor the evolutionary continuity that I had, even until today.

I researched for less toxic resins with better properties and excellent color. I designed a more efficient manufacturing process. I got good results at the surf contests and with my clients. Furthermore, I constantly marketed my blanks and surfboards by investing in publicity and sponsoring the most outstanding surfers. EPS foams are much lighter than regular foams, and this gave my boards an edge at the surfing contests as well with the surf aficionado. The epoxy resin is stronger than the polyester resin. Thanks to the combination of these properties we have excellent high performance surfboards. The rest is history.

1978: First “Focus” surfboards made of polyurethane foam and polyester resin.

1979: Clark Foam (polyurethane foam) closes its Lima facilities.

1984: First “Focus” surfboards made of EPS foam and epoxy resin. Team riders Germán Aguirre and Omar Renteros successfully test them.

1985: Introduction of the unidirectional carbon fibers used in the longboards of the national champion Dayal Gayoso and the surfboards of Gustavo Valdivia to ride La Herradura.

1988: “Niko” Wilhelmi and “Wayo” Whilar tried EPS foam and epoxy in their surfboards

1989: I went to live in the United States. My brother Luis took the post for the Focus boards in Peru. In California I manufactured the first epoxy boards made of extruded polystyrene (XPS) with the brand SVF and with Dow Chemical collaboration.

1999: My cousin Javier Huarcaya took the post of the technology started by SVF and continued developing with success the growing of XTR foam and surfboards in California and the rest of the USA.

2000: I developed a new epoxy resin, with faster drying and better properties. I improved the production cycles and the resin had a better color.

2005: Clark Foam closed its facilities in California due to environmental problems with government regulatory agencies.

2006: My Company ECB (Experts Composites & Blanks) began operations in Peru manufacturing molded EPS foams. These were more cohesive and water tight foams and more resistant to delamination. Well known Peruvian shapers and surfboards manufacturers like Klimax, Wayo, Tello, Jerí, Focus, Lazy and foreigners surf brands as well used my new blanks with success.

2009: I moved back to Peru; I introduced my new and original F1 epoxy resin.

2010: I developed the ECB epoxy resin with additives. Its formula better withstood the UV lights and it had a better color. I developed a resin of slow exothermic reaction; one of the benefits of this resin was that it created less heat when it was cured, to be used on the installation of the FCS fins system.

2011: I introduced the market to a much lighter blank for SUP.

2012: We improved the stringers by using unidirectional wood veneer. I started working with “Piccolo” Clemente.

2013: Piccolo won the ASP-WSL World Surfing Championship Longboard division using the Peruvian EPS/Epoxy technology from ECB in his boards.

2014: We reintroduced reinforcements made of hemp and nylon in the EPS blanks with paper stringers. These blanks are super light with a density ratio of 16, 20 and 30Kg/ m³. Piccolo Clemente continues winning in the national and international Surfing contests with his epoxy longboards made with ECB technology and materials.

End of the blue page.

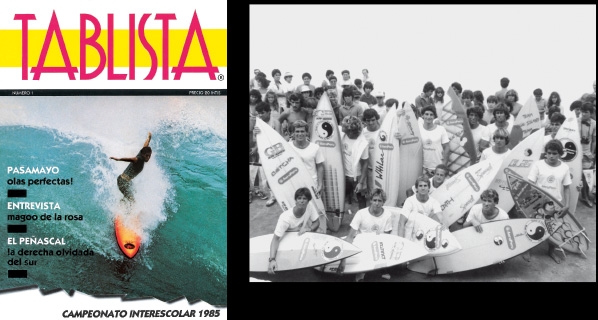

December 1985 saw the launch of a new, beautiful Peruvian surfing magazine. It would touch and change all aspects related to surfing in the country. Over the past three decades Tablista has given Peru the most eloquent reports and interviews, the most splendid photos, and the most creative tales, cartoon characters and paintings. Right off the bat big mainstream companies, as well as surf companies, were eager to publish their advertisements in the magazine.

Tablista was born thanks to the energy and stamina of Javier Fernández Urbina, known as “Ocu”, and Javier Huarcaya Pro, often called “Papaya.” Both men fell in love with surfing in the summer of 1978 and thanks to their passion Tablista has launched the careers of surfers and surf media professionals in Peru. Photographers, comic strip creators, painters and writers alike, all got their opportunity to shine on the pages of Tablista.

Since its first inception, Tablista has thoroughly scrutinized the wonderful history of our ancient sport. Its editors are famous for fearlessly announcing irrational attacks against our waves and it supports organizations dedicated to the preservation of the ocean. Having the whole Tablista collection is a treasure that a surf mom or dad will happily pass down to their heirs. Tablista magazine has survived thanks to its creativity and humor during any crisis or turmoil that has threatened our economy since its first issue was published. One can find Tablista in the newsstands and bookstores. Its articles and reports are very diverse, covering everything from environmental issues, surfing politics, and the unstoppable evolution of surfing in Peru.

In February 1986, the CONTA was replaced by, or rather turned into, the Federación Peruana de Tabla (FEPTA, Peruvian Surfing Federation) thanks to the wisdom and vision of then-president of the Instituto Peruano del Deporte (IPD, Peruvian Sport Institute), Víctor Castagnola. The new Federation was founded in 1962, and thanks to CONTA’s presidents Luis Anavitarte and José Whilar, it was renovated and modernized during their terms, making the transition from a mere Commission to a Federation efficiently and smoothly. The first president of FEPTA was Ode Aguad Abusada. With this new status, Peruvian surfing was able to obtain more funds to support its development and activities. Thanks to the financial influx, FEPTA authorities were able to organize yearly events on a regular basis in different beaches during the whole year. FEPTA also pushed for the Peruvian Surfing Team’s participation in the ISA competitions. The goal was to win a world title again.

Surfing in Peru began to change and was becoming more professional thanks the constant organization of surfing championships supported or organized by FEPTA and local surfing leagues such as Cañete, La Punta, Huanchaco, Pacasmayo, Pimentel and Piura. For instance, Huanchaco celebrated two main surfing contests every two years, one at the end of January called Marinera (a traditional northern dance) and the other in October called Primavera (Spanish for spring). Both events were hugely popular and the best surfers from Lima, Pacasmayo and other beaches competed there, enjoying the wonderful and consistent waves of Huanchaco. Pacasmayo, with its world-class wave El Faro also celebrated a quite popular surfing contest every Easter called Tradicional de Semana Santa (Traditional Easter competition). Again, the best Peruvian surfers competed at El Faro and during the three-day celebration surfers and the attending public enjoyed great rock music concerts.

During the ‘80s Peru suffered from terrorist attacks conducted by the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) and daily Peruvian activities were severely impacted by the terrorist organization. Surfers’ lives and habits were also negatively impacted and surf trips were limited to nearby spots. Important surfing contests like the Jose Duany Invitational were not run some years. But despite all these difficulties, Peruvian surfers managed to stay stoked.

The late Oscar Malpartida won the national surfing title back to back in 1980 and 1981, adding those two titles to the one he had already won in 1972. Gordo Barreda has explained that his surfing nemesis was Malpartida, and while he was telling his story he conducted himself with a sense of respect and there was genuine care for Malpartida in his voice.

In 1982, Raúl “Patero” Calle was the most radical surfer on a single-fin board, yet the national title that year went to Brad Waller, the most innovative surfer. Waller was using a carved fin (outline of the fin only), designed by his father Harold E. Waller, which allowed Waller to practice 360 degree turns inside the barrel.

Luis Miguel De La Rosa Toro, known as Magoo, was the winner of the national title in 1983. Magoo was admired for his radical backside bottom turns and for hitting the lip of the wave with his twelve o´clock turns. He was a protégé of Gordo Barreda and was one of the first surfers to ride Cabo Blanco. De La Rosa would go on to win the national surfing title seven times, still the record today.

In 1984 the national title was won by the great Mario Chocano. Luis Fernando “Luifer” Gómez De La Torre won the national title the following year. Luifer is nowadays a big-wave charger and every time Pico Alto is on, you can see him dropping into a bomb. Carlos “Chalo” Espejo won the national title twice, in 1986 and 1987 and was also one of Gordo’s protégés. He learned a great deal about surfing from his teacher, and as result during the ‘80s Chalo was one of the most outstanding surfers in Peru. Another big name of the ‘80s was José “Titi” De Col, national champion in 1988 and 1989. De Col was very savvy and competitive. He would constantly travel around the world searching for surf and charged big waves in Hawaii. Still, his favorite spot was Los Órganos, one of the magic waves of Northern Peru, where he built a beautiful house.

Names like César “Mr. Tube” Aspíllaga, who by the way has more miles under the barrel than any other surfer in Peru, were always seen in the finals of the ‘80s contests. Meanwhile, Roberto Meza’s surfing style was characterized by powerful roundhouse cutback maneuvers. Juan Manuel Zegarra “Sugui” also was a standout during this decade. Zegarra was mentored by “Gordo” Barreda, just like De La Rosa and Espejo. Every time he went out to surf in La Pampilla he monopolized up to 80 percent of the waves during the surf session.

The beautiful and brave Rocío Larrañaga was one of the most exceptional surfers. She was a superb paddler and used to compete in prone races against men, defeating many of them with ease. Surfers are eternally grateful for Rocío for her discovery of San Gallán. Lucía “Taty” and Pilar Yrigoyen, both talented and brave young women, decided to emulate Rocío by embracing the surfing way of life. In Northern Peru, Jesús “Zorro” Florián, a local from Chicama, was perhaps the luckiest guy in the world. He got to surf the long and beautiful wave with no crowd whatsoever. The fun waves of Huanchaco also hosted several great surfers. One of them, the local Luis “Chino” Suzuki, was a fearless competitor during the national surfing contest held in his beach town.

In this accomplished list of the ‘80s we must add the names of Milton Whilar, Max De La Rosa Toro, Javier Huarcaya, Oswaldo Vélez, Alberto “Pato” Maldonado, Martín Almenara, Martín Jerí, Luis “Chato” Rojas, Carlos Velarde (Big wave rider), Rodolfo Klima (Klimax surfboards founder), Fernando Paraud, Pierre Rodrigo (one of the best surfers at La Herradura and Cabo Blanco), Ricardo Labarthe (very fluid in both powerful waves and barrel waves), Omar Renteros (an extremely skillful radical surfer), Rafael “Mota” Navarro, Diego Velarde and the Rhode brothers Walter and Christian, of which the latter did not hesitate to hit the road to Panic Point every time the surf forecast was announcing a big swell.

CHAPTER ONE: THE FISHERMEN SURFERS

CHAPTER TWO: NAVIGATION IN ANCIENT PERU

CHAPTER THREE: A PLAUSIBLE PERU-POLYNESIA CONNECTION

CHAPTER FOUR: THE HAWAIIAN TRADITION

CHAPTER FIVE: CARLOS DOGNY LARCO AND THE CLUB WAIKIKI (1938 - 1949)

CHAPTER SIX: THE FIRST YEARS WERE INSTITUTIONAL (1950 - 1959)

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE AMAZING DECADE (1960 - 1969)

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE RISE OF THE BROTHERS OF THE SEA (1970 - 1979)

CHAPTER NINE: EVOLVE WITH YOUR SPORT (1980 - 1989)

CHAPTER TEN: THE BEGINNING OF MODERN HISTORY (1990 - 1999)

CHAPTER ELEVEN: PERU: TOP LATIN AMERICAN SURFING POWER (2000 - 2009)